Kynn Bartlett wears many hats. He co-founded a successful Web design company; he is an author, an educator, and public speaker; and he’s also a very witty person. Most of all though, Kynn is renowned for his expertise in Internet Accessibility.

He talked recently with SitePoint about usability and accessiblity, and argued the case for the role of design in supporting these two objectives…

SitePoint: Hi Kynn, thanks for agreeing to this interview. I would like to start off by asking you about your roots. What made you decide to work with new media? And, specifically, how did you get involved with the topic of accessibility?

Thanks for this opportunity; I’m pleased and honored by the chance to shed some light on what will be an important issue for Web developers for years to come.

I’ve been using the Internet for years now, since 1986; to my embarrassment, I recently came across my earliest Usenet posts. When the Web was developed, I was working as a graveyard shift junior sysadmin for a special effects studio. My job literally consisted of putting in a backup tape, typing a shell command, taking it out two hours later, and repeating the process until the day’s FX work was done. This gave me plenty of time to explore new technologies at 5 am, and I became first the defacto and then official Webmaster for Rhythm and Hues studios in 1994.

In 1995, I quit R&H to work for an Orange County Web development company which no longer exists; after a few months, I told my wife Liz, “If these clowns can do it, anyone can.” She responded with “Well, why can’t we?” That September, we started Idyll Mountain Internet and Liz still runs it today; she has two employees and they’ve designed and hosted over one hundred sites.

While learning the ropes of professional Web development, the mailing lists run by the HTML Writers’ Guild proved quite useful to me, and in June 1996 I was asked to join the Governing Board. Little did I know that I’d make a commitment of more than 5 years which would see the HWG grow from 6,000 to 125,000 members, or that I would end up serving as President not once but three times.

An activity I pushed hard for — and succeeded in putting into action — was the Guild’s membership in the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) as the first and only association of working Web developers to join the W3C. This is an important role, as all other W3C members, shaping the future of Web standards and the evolution of the Web, represent either commercial or academic interests. The voices of the front-line Web developers weren’t being heard, and the HWG’s membership in the W3C offered a conduit for them to make their opinions known.

As a W3C member, the HTML Writers Guild could appoint volunteers to contribute their time and expertise to working groups. When the opportunity came to get involved in the Web Accessibility Initiative, I made a commitment to not only use the HWG’s membership to advance Guild causes in the W3C, but also to educate our own members regarding the benefits of an accessible approach to Web development.

This commitment led to the establishment of the Accessible Web Authoring Resources and Education (AWARE) Center, as well as my online courses in Web accessibility. Both of these continue to be supported by the International Webmasters Association, which took over the operations of the HWG after a merger in summer 2001. This April is the fifth annual HWG (now HWG/IWA) Web Accessibility Month, a month-long focus on the need for accessibility awareness by Web developers.

SP: What influenced you most within the field of accessibility?

When it comes down to it, I suppose it’s a simple concept of fairness and justice, as naive as that may seem in this day and age. It’s simply the right thing to do.

Now, once I’ve said that, I’ve got to define what exactly I mean when we’re talking about Web accessibility. Ultimately, it’s not a set of checklists, dos-and-don’ts, and arcane rules on tags; it’s closer to a process and a methodology, but really it’s a mindset. That mindset says, “the Web is an adaptable medium, allowing each person to access information in the way that best suits his or her needs.” As I define Web accessibility, it’s about inclusion and embracing diversity. It’s about caring that your audience — no matter who they are and what they can or can’t do — is able to use your site.

Web accessibility is really a human rights issue. As more and more aspects of daily life — from shopping to news to voting — move online, it’s crucial to ensure that we don’t inadvertently exclude those people who can most benefit from this ongoing revolution and evolution. A user who can’t drive to the store has a lot to gain from an online grocery service; a user without the ability to read the printed newspaper will find great value in online editions. These are real benefits of the Internet age, and they’re often taken for granted by those who don’t have major disabilities.

If you’ve got a mindset that includes those users as a valid part of your user group, you will design a site that they can use — you can’t help it. It becomes second nature to ensure accessibility for a wide audience. If, however, you don’t include those users — either because you haven’t thought about it (ignorance) or because you simply don’t care (malice) — it’s very likely you’ll construct a Website which represents serious barriers for your users.

SP: Can you highlight the major constraints that you encounter in your work on a regular basis?

The most obvious accessibility problem on the Web — to the point that I’ve identified it as “the poster child for Web accessibility” — is the lack of alt attributes on images. Without textual alternatives for graphics, users of screenreader software will be told only that an image appears on the page, and won’t have any idea what that image represents. Is it a simple illustration, a chart, a navigation menu, or just yet another darned cat picture? Without alternative text, there’s no way of knowing. The solution is simple — give a text equivalent for each image that duplicates the function of the graphic.

The next most common accessibility error relates to the use of JavaScript, Java, Flash, PDF, multimedia presentations, and other languages and formats which aren’t supported by assistive technology (AT). Assistive technology is a broad category which includes both hardware and software (such as screenreaders) that allow computer users with special needs to run programs, providing input or output functions, or both. Most ATs are unable to handle complicated Web programming effects and file formats which haven’t been designed with accessibility in mind. Solving those problems involves setting up alternate ways to access the same functionality, such as a server-side script paralleling a Java applet or an HTML equivalent for a PDF form.

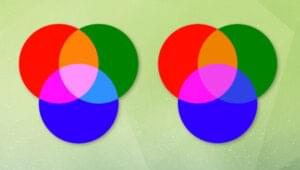

Color use, as related to Web accessibility, is often misunderstood; the use of color itself does not inherently present accessibility barriers. However, the use of color as the only indication of important content can cause a number of problems for users who can’t perceive colors the same way you or I can. For example, let’s say that a train schedule indicates that all times marked in green represent A.M., and all marked in red represent P.M. Someone with red-green color blindness might not be able to tell the difference, and would have no idea what time to arrive at the station. To fix this, you wouldn’t turn off the colors, you’d simply add “A.M.” or “P.M.” to each time on the schedule.

You’ll notice that in each of these cases I didn’t say to take something away, but rather to add something. Web accessibility, when done right, is about expanding your audience by extending your site, not about removing something because it’s “bad.” Don’t tear down the Flash presentation — just provide the important content with an HTML link. Don’t remove your graphics — add alt text so everyone can use the site.

In fact, graphics themselves can increase the accessibility for a number of users with disabilities, something you may not have heard before. Accessibility isn’t simply about blind users; many users have cognitive disabilities which make it harder for them to read large blocks of text. Through illustrations and meaningful icons, you can make your site easier for these users with reading or comprehension difficulties. Clear, simple writing and links to definitions or glossaries can also improve comprehension, which also gives benefits to younger users or international users for whom English isn’t their primary language.

SP: People often exchange the terms accessibility and usability as if they were the same thing, what would you say to try and explain the difference?

Accessibility and usability are very much related technologies, but where one stops and the other begins it’s hard to say. Both include a focus on the needs of the user and a desire to improve that user’s experience; some will claim that accessibility is a subset of usability, while others will claim it’s the other way around. Both are important and a vital part of delivering Web services which benefit our audiences.

The way I see it is this — accessibility is about whether or not someone can get to the content, and usability is about how easy, pleasant, and efficient it is to do so. For example, let’s consider a university library. There is a book stored on the 4th floor which Nathan would like to read, but he’s in a wheelchair, and there are no elevators. The book’s contents are inaccessible to him.

So let’s assume he goes to the librarian and talks to them about this. The librarian then says, “Oh, okay, I’ll go get it for you.” She runs up the stairs, grabs the book, and brings it down to Nathan. Nathan now has access to the content; the book is in his hand and he can read it. However, let’s examine the usability — the librarian has to be available, not busy with someone else, and he has spend time asking for the book and waiting for it to be brought down. What’s more, he can’t browse through the other books on the same shelf, so he’s unable to easily locate other books on the same topic. The usability is much lower than if there were an elevator installed, but no one can deny that he has access to the book.

As Web developers, we have to consider both issues, for our disabled and non-disabled users alike. Are they able to access the content, and if so, is it easy for them to do so?

SP: How would you undertake the enormous task of convincing designers that accessibility IS important, and there is a place for both extraordinary design and a high level of accessibility?

Well, I don’t actually believe it’s an enormous task. I think it’s a simple and straightforward proposition to suggest that everyone — not just those who are physically perfect — should be able to use this marvellous tool of the 21st century. Nearly anyone except the coldest of hearts would agree that if you can make something that can be used by more people instead of fewer, you should do it.

The problem here is that somewhere the wrong message got sent. The impression has been made that accessible Web design means boring Web design. Part of that is the fault of Web accessibility proponents, who have a tendency to label anything visually interesting as “worthless bells and whistles” and an emphasis that “content is king” with an unspoken disdain for appealing presentations. Personally, I like visual sites which are attractive and well-done; and as noted before, users with cognitive disabilities can gain much from a solid, well-illustrated site.

Now, you wouldn’t be able to tell that I like attractive sites from looking at my own personal site! Not all of us are artists and I include myself in the “not” camp on this one. What’s worse, though, than my poorly illustrated site is Jakob Nielsen’s defiantly proud text-only site. While Jakob often makes excellent points, his insistence on a pure textual site results in one without illustrations or decent graphical design. Such an attitude is basically a rejection of the large body of knowledge possessed by graphical artists about how visual information is processed by those of us who are fortunate to be able to see. Rather than denying this knowledge, Jakob and others — myself included — should embrace it as part of our understanding of how to make audience-centred Websites.

A dynamic visual design isn’t at all at odds with an accessible content interface. The two are complementary disciplines, and there’s much that the accessibility engineer can learn from the graphic artist, and vice versa.

SP: Why, in your opinion, is accessibility often relegated to an afterthought?

Because there’s so much else to worry about. Within the safe shelter of the Web Accessibility Initiative or other accessibility groups, it’s easy to forget that there’s anything else important in the world, but the truth is that Web developers these days have more on their minds than ever before. A Web developer today has to be some combination of graphic artist, programmer, user interface designer, database administrator, marketing expert, sysadmin, usability guru, markup language developer, animator, and systems integrator, in varying amounts. We’ve come a long way from just making HTML pages that look good in Lynx and Mosaic.

With those other issues competing for his or her time, is it any wonder that the typical Web developer hasn’t placed Web accessibility at the forefront of her thoughts, if she’s even aware of the issues? Most of the time, Web accessibility isn’t a consideration because the Web developers are simply ignorant — and I mean that in the most judgment-neutral way. They just don’t know, and despite what some may tell you, there’s no shame in not knowing. It’s not like Web developers are born with the innate knowledge of how accessible Websites are made, nor is it considered an essential part of most learning programs, from classes to books.

But let’s assume that our hypothetical Web developer has considered the issues and decided to learn more. Where do they look? Well, the Web Accessibility Initiative is a good start, and pretty much the definitive source for Web accessibility knowledge. So they go there, and do some reading, and what does they find? The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0, a long checklist that you use on a completed site in order to see if it’s likely to be accessible. They can use the Bobby program from CAST to review the site for compliance with the WCAG recommendation.

By reducing Web accessibility to a QA process with checklists and evaluation tools, the W3C is in effect endorsing the notion of Web accessibility as an afterthought. I can’t blame Web designers with no specific expertise in accessibility for getting the wrong impression when the leading body for Web accessibility sends the same message.

The real lesson to be learned is that Web accessibility is about the process, which flows from the mindset — the idea that all along you need to consider not only how your site will be used, but also who will use it.

SP: Who are the big players in accessibility and what Websites do you visit regularly on the subject?

The centre of the Web accessibility universe is the Web Accessibility Initiative at the W3C. This branch of the international consortium for Web specifications is concerned with creating guidelines and recommendations for Web developers, browser programmers, and authoring tool creators to improve access by people with disabilities.

Of particular importance to anyone who works for the US federal government is the Section 508 Website run by the Access Board. Section 508 is a federal policy which establishes that U.S. government Websites (and other computer systems) must be accessible to people with disabilities, both employees of the agencies and the general public. The Section 508 regulations for sites are a partial adaptation of the W3C’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines.

Two good informative sites are the Web Accessibility In Mind (WebAIM) and International Center for Disability Resources on the Internet (ICDRI) sites. WebAIM has extensive tutorials, demonstrations, and research articles, while ICDRI has a great collection of policy links and information on Web use by disabled users.

Wisconsin’s Trace Center, the University of Toronto’s ATRC, and the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) are all also great sites. More links can be found on the AWARE Center’s Website.

SP: What advice can you give to Web developers who want to get involved, advocate and educate about Web accessibility?

Learn, create, and share. That’s the magic formula.

Learn more about Web accessibility by visiting the sites listed above, by taking a Web accessibility course, or by joining a mailing list on Web accessibility. Good lists are run by the HTML Writers Guild, WebAIM, Trace, and the W3C.

Create by putting these principles into action on your own Website, blending your exciting visual designs with the principles of Web accessibility that let you extend those designs to all audiences.

Share by telling other Web developers, your co-workers, and your clients why it’s important that everyone has access to the 21st Century Web. This is not about dogmatic HTML validation or about dumbing-down Websites — this is about real people like you or I, who want to use the Web as much as we do.

I very much recommend getting to know some users with disabilities. Join a Web or email group for users with special needs, or meet some in your own community. Talk to them about what’s easy to use, and what’s hard. Get critiques of your own sites and others. Don’t just rely on some W3C document or a book to tell you how to create accessible Web sites. Accessibility is about people, and we should never lose sight of that.

SP: I read with interest that you are working on a book about CSS. Can you explain how that came about and do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

I’ve been doing technical editing for several years now, and quite enjoyed it. I also had the opportunity to write a few chapters here and there for various books, most of which you probably haven’t, and probably won’t ever read.

After the most recent tech edit, I was approached at almost the same time by SAMS, asking me to submit a proposal for a “Teach Yourself CSS in 24 Hours” book, and by Studio B, a literary agency specializing in computer books. While not everyone enjoys having an agent, I found that the folks at Studio B were quite helpful in the financial negotiations, which has always been an uncomfortable hurdle for me. Both the SAMS and Studio B people have been great, and quite patient with me on my first book.

I feel a little odd about giving advice to aspiring writers before my first book is even finished, but I’ll try anyway. Be good at writing first. Be good at research next. And most importantly, be disciplined and write consistently.

SP: And finally, what’s next for Internet accessibility? Can you predict what things will be like 2 years from now, five years from now? Will XML be changing the face of things to come?

Accessibility of the Internet is still a very young discipline, and is going through many of the growing pains that fields of study experience as they’re being developed. In the next few years we’ll see a greater incorporation of other disciplines, from graphic design to usability, into the core body of accessibility knowledge. Our understanding of certain disability types, such as users with dyslexia, or photosensitive epilepsy, will expand as we encompass a view of accessibility which isn’t simply “alt text for blind guys.”

The growth of the Internet to all aspects of society — American and internationally — will only increase the need for accessibility for all. As more of the older generations get online, Web developers will need to gain an understanding of the age-related changes experienced by people as they grow older, both physical and psychological. Would you design a site the same way for a user born in 1986 as one born in 1926?

International growth of Internet services will result in a broader group of people, many of whose needs will be met by the same techniques that enable access by disabled users. Slower connections, minute charges for access, or lack of English proficiency are all solved problems on a Website designed to be accessible to a broad audience.

XML has already started to change the Web accessibility landscape, from SVG and SMIL to XSLT and XForms, and we’ll continue to see XML play a key role in accessibility. Work at the W3C to produce “the Semantic Web”, while tending toward head-in-the-clouds dogmatism, also has the potential for some particularly neat innovations.

One technology which I’ve been watching develop (and helping a little) over the years is the idea of adaptable Websites that specifically reconfigure themselves to meet the needs of their users. This can be done through a variety of ways, from simply offering different template choices at a database-driven site, to pure XML solutions using XSLT driven by CC/PP to dynamically create a unique user interface. This kind of adaptivity allows us Web developers to have our cake and eat it too — design an optimal appearance for visual users, and still ensure that all users with disabilities receive a site that’s optimized for their use as well.

The Web barely existed 10 years ago. The concept of Web accessibility barely existed 5 years ago. The next few years as the Web continues to change will be crucial, not only for the sake of people who currently have disabilities, but for those of us who don’t. As we grow older, will we be able to use this new information medium we’ve built? I sure hope so. Let’s build it right, for everyone’s benefit.

SP: Thanks for talking to SitePoint Kynn, good luck with all your plans!

Nicky is a Community administrator for the SitePoint Forums. She's an advocate of accessibility and her research has been presented at international conferences. Nicky loves to travel, especially to Gibraltar, and is friends with anyone who offers her ice-cream or chocolate.