Understanding ECMAScript 6: Class and Inheritance

Key Takeaways

- ES6 allows developers to simulate classes and inheritance with JavaScript, a prototype-oriented language, facilitating the creation of large applications for the web.

- ES6 introduces new semantics to JavaScript, such as not being able to call a constructor without ‘new’ or construct methods with ‘new’, and methods being non-enumerable.

- The ‘extends’ keyword in ES6 allows developers to specialize a class into a child class while keeping a reference to the root class with the ‘super’ keyword, simplifying inheritance.

- TypeScript, which looks similar to ES6 without the types, is a useful tool to generate JavaScript code and understand ES6 better, especially with TypeScript’s support for ES6 code.

This article is part of a web dev tech series from Microsoft. Thank you for supporting the partners who make SitePoint possible.

I’d like to share with you a series of articles about ECMAScript 6 , sharing my passion for it and explaining how it can work for you. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I did writing them.

First, I work in Microsoft on the browser rendering engine for Project Spartan, which is a vast improvement over the Internet Explorer engine we got to know (and love?) over the years. My personal favorite feature of it is that it supports a lot of ECMAScript 6. To me, this is a massive benefit to writing large applications for the web.

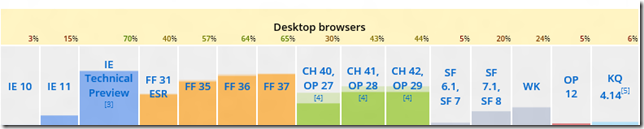

We now have almost 70% of ECMAScript 6 features in Project Spartan so far according to this compatibility table and ES6 on status.modern.IE.

I love JavaScript, but when it comes to working on large projects like Babylon.js, I prefer TypeScript which is now powering Angular 2 btw. The reason is that JavaScript (or otherwise known as ECMAScript 5) doesn’t have all the syntax features I am used to from other languages I write large projects in. I miss classes and inheritance, for instance.

So without further ado, let’s get into just that:

Creating a class

JavaScript is a prototype oriented language and it is possible to simulate classes and inheritance with ECMAScript 5.

The flexibility of functions in JavaScript allows us to simulate encapsulation we are used to when dealing with classes. The trick we can use for that is to extend the prototype of an object:

var Animal = (function () {

function Animal(name) {

this.name = name;

}

// Methods

Animal.prototype.doSomething = function () {

console.log("I'm a " + this.name);

};

return Animal;

})();

var lion = new Animal("Lion");

lion.doSomething();We can see here that we defined a class with properties and methods.

The constructor is defined by the function itself (function Animal) where we can instantiate properties. By using the prototype we can define functions that will be considered like instance methods.

This works, but it assumes you know about prototypical inheritance and for someone coming from a class-based language it looks very confusing. Weirdly enough, JavaScript has a class keyword, but it doesn’t do anything. ECMAScript 6 now makes this work and allows for shorter code:

class AnimalES6 {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

doSomething() {

console.log("I'm a " + this.name);

}

}

var lionES6 = new AnimalES6("Lion");

lionES6.doSomething();The result is the same, but this is easier to write and read for developers who are used to writing classes. There is no need for the prototype and you can use the constructor keyword to define the constructor.

Furthermore, classes introduce a number of new semantics that aren’t present in the ECMAScript 5 equivalent. For example, you cannot call a constructor without new or you cannot attempt to construct methods with new. Another change is that methods are non-enumerable.

Interesting point here: Both versions can live side by side.

At the end of the day, even with the new keywords you end up with a function with a prototype where a function was added. A method here is simply a function property on your object.

One other core feature of class-based development, getters and setters, are also supported in ES6. This makes it much more obvious what a method is supposed to do:

class AnimalES6 {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this._age = 0;

}

get age() {

return this._age;

}

set age(value) {

if (value < 0) {

console.log("We do not support undead animals");

}

this._age = value;

}

doSomething() {

console.log("I'm a " + this.name);

}

}

var lionES6 = new AnimalES6("Lion");

lionES6.doSomething();

lionES6.age = 5;Pretty handy, right?

But we can see here a common caveat of JavaScript: the “not really private” private member (_age). I wrote an article some time ago on this topic.

Thankfully, we now have a better way to do this with a new feature of ECMAScript 6 : symbols:

var ageSymbol = Symbol();

class AnimalES6 {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this[ageSymbol] = 0;

}

get age() {

return this[ageSymbol];

}

set age(value) {

if (value < 0) {

console.log("We do not support undead animals");

}

this[ageSymbol] = value;

}

doSomething() {

console.log("I'm a " + this.name);

}

}

var lionES6 = new AnimalES6("Lion");

lionES6.doSomething();

lionES6.age = 5;So what’s a symbol? This is a unique and immutable data type that could be used as an identifier for object properties. If you don’t have the symbol, you cannot access the property.

This leads to a more “private” member access.

Or, at least, less easily accessible. Symbols are useful for the uniqueness of the name, but uniqueness doesn’t imply privacy. Uniqueness just means that if you need a key that must not conflict with any other key, create a new symbol.

But this is not really private yet because thanks to Object.getOwnPropertySymbols, downstream consumers can access your symbol properties.

Handling inheritance

Once we have classes, we also want to have inheritance. It is – once again – possible to simulate inheritance in ES5, but it was pretty complex to do.

For instance, here what is produced by TypeScript to simulate inheritance:

var __extends = this.__extends || function (d, b) {

for (var p in b) if (b.hasOwnProperty(p)) d[p] = b[p];

function __() { this.constructor = d; }

__.prototype = b.prototype;

d.prototype = new __();

};

var SwitchBooleanAction = (function (_super) {

__extends(SwitchBooleanAction, _super);

function SwitchBooleanAction(triggerOptions, target, propertyPath, condition) {

_super.call(this, triggerOptions, condition);

this.propertyPath = propertyPath;

this._target = target;

}

SwitchBooleanAction.prototype.execute = function () {

this._target[this._property] = !this._target[this._property];

};

return SwitchBooleanAction;

})(BABYLON.Action);Not really easy to read.

But the ECMAScript 6 alternative is better:

var legsCountSymbol = Symbol();

class InsectES6 extends AnimalES6 {

constructor(name) {

super(name);

this[legsCountSymbol] = 0;

}

get legsCount() {

return this[legsCountSymbol];

}

set legsCount(value) {

if (value < 0) {

console.log("We do not support nether or interstellar insects");

}

this[legsCountSymbol] = value;

}

doSomething() {

super.doSomething();

console.log("And I have " + this[legsCountSymbol] + " legs!");

}

}

var spiderES6 = new InsectES6("Spider");

spiderES6.legsCount = 8;

spiderES6.doSomething();Thanks to the extends keyword you can specialize a class into a child class while keeping reference to the root class with the super keyword.

With all these great additions, it is now possible to create classes and work with inheritance without dealing with prototype voodoo magic.

Why using TypeScript is even more relevant than before…

With all these new features being available on our browsers, I think it’s even more important to use TypeScript to generate JavaScript code.

First off, all the latest versions of TypeScript (1.4) started adding support for ECMAScript 6 code (with let and const keywords) so you just have to keep your existing TypeScript code and enable this new option to start generating ECMAScript 6 code.

But if you look closely at some TypeScript code you will find that it looks like ECMAScript 6 without the types. So learning TypeScript today is a great way to understand ECMAScript 6 tomorrow!

Conclusion

Using TypeScript, you can have all this now, across browsers, as your code gets converted into ECMASCript 5. If you want to use ECMAScript 6 directly in the browser, you can upgrade to Windows 10 and test with Project Spartan’s rendering engine there. If you don’t want to do that just to try some new browser features, you can also access a Windows 10 computer with Project Spartan here. This also works on your MacOS or Linux box.

Of course Project Spartan is not the only browser that supports the open standard ES6. Other browsers are also on board and you can track the level of support here.

The future of JavaScript with ECMAScript 6 is bright and honestly I can’t wait to see it widely supported on all modern browsers!

This article is part of a web dev tech series from Microsoft. We’re excited to share Project Spartan and its new rendering engine with you. Get free virtual machines or test remotely on your Mac, iOS, Android, or Windows device at modern.IE.

Frequently Asked Questions about ECMAScript 6 Class Inheritance

What is ECMAScript 6 and how does it differ from previous versions?

ECMAScript 6, also known as ES6 or ECMAScript 2015, is the sixth edition of the ECMAScript language specification. It introduces several new features and improvements over previous versions, including classes, modules, arrow functions, promises, and more. These features make JavaScript more powerful and easier to work with, especially for large-scale applications.

How does class inheritance work in ECMAScript 6?

In ES6, class inheritance is a way of creating a new class that inherits properties and methods from another class. This is done using the ‘extends’ keyword. The new class, known as the subclass, can then add or override properties and methods from the superclass. This makes it easier to create complex object-oriented programs in JavaScript.

What is the ‘super’ keyword in ECMAScript 6?

The ‘super’ keyword in ES6 is used within a subclass to call functions on the superclass. This is particularly useful in the constructor method of a subclass, where you often need to call the constructor of the superclass before adding or modifying properties.

How do I use getters and setters in ECMAScript 6 classes?

In ES6 classes, you can use getters and setters to control how properties are accessed and modified. A getter is a method that gets the value of a specific property, while a setter is a method that sets the value of a specific property. They are defined using the ‘get’ and ‘set’ keywords, respectively.

Can I use ECMAScript 6 features in all browsers?

While most modern browsers support many ES6 features, not all features are supported in all browsers, especially older ones. Therefore, it’s important to use tools like Babel to transpile your ES6 code into ES5, which has wider browser support.

What are arrow functions in ECMAScript 6?

Arrow functions are a new type of function in ES6 that have a shorter syntax and lexically bind the ‘this’ value. This makes them particularly useful for callbacks and functional programming patterns.

How do I use modules in ECMAScript 6?

ES6 introduces a native module system that allows you to split your code into separate files and import/export functions, objects, or values between them. This is done using the ‘import’ and ‘export’ keywords.

What are promises in ECMAScript 6?

Promises are a new feature in ES6 that provide a more powerful and flexible way of handling asynchronous operations. A promise represents a value that may not be available yet, but will be at some point in the future or never.

How does the ‘let’ and ‘const’ keywords work in ECMAScript 6?

The ‘let’ and ‘const’ keywords in ES6 provide block scope variable declaration, which is a more intuitive and safer way of declaring variables compared to the ‘var’ keyword. The ‘let’ keyword is used for variables that can be reassigned, while the ‘const’ keyword is used for variables that cannot be reassigned.

What is destructuring assignment in ECMAScript 6?

Destructuring assignment is a feature in ES6 that allows you to unpack values from arrays or properties from objects into distinct variables. This can make your code more concise and easier to read.

David Catuhe is a Principal Program Manager at Microsoft focusing on web development. He is author of the babylon.js framework for building 3D games with HTML5 and WebGL. Read his blog on MSDN or follow him on Twitter.