While they’re not absolutely necessary for Website functionality, images help improve the appearance of a site. With a few good quality, highly optimised images, you can give your site the edge it needs to leave a lasting impression. The problem is that many Webmasters, both novice and experienced, don’t feel confident when it comes to creating clean looking graphics and optimising them for the Web.

On the Web today, GIF, PNG and JPEG are the most common and widely-supported image file formats. But which should you use? Well, this question is impossible to answer without a few extra considerations. In this article, we’ll look at some of the important differences between GIF, PNG and JPEG images, and discuss how you can get the best quality from all your Web graphics.

Key Takeaways

- GIF and PNG formats excel in compressing images with flat, solid colors and text, making them ideal for logos and web graphics.

- JPEG is best suited for photographs and complex images due to its efficient compression of natural-looking images.

- PNG offers advantages over GIF, such as support for more colors and better transparency options, though it might not be fully supported in all web browsers.

- JPEG compression can introduce artifacts, which may not be noticeable at normal viewing sizes but can become apparent upon closer inspection or with improper use.

- When optimizing images for the web, consider the image’s content and desired quality to choose the most appropriate format between GIF, PNG, and JPEG.

- Keeping an uncompressed original is crucial as it allows for re-optimization and format change without quality degradation.

The Struggle Between GIF and PNG

The GIF and PNG formats are ideal for compressing graphics that contain flat areas of plain colour, as well as text.

The Faithful GIF

For many years, the only data that flowed in and out of our modems was text: ASCII text. A modem’s primary job, once upon a time, was to send and receive letters, numbers, and 66 other assorted characters.

This isn’t particularly surprising if we consider that computer graphics displays were rare, and modems were so slow that they took 3 to 4 seconds to transmit a single sentence.

The GIF file format, created by Compuserve in 1987, was designed to fit as much image information as possible into the smallest space. It uses a loss-less compression algorithm (LZW) that is not uncommon today.

The colours in a GIF file are indexed in a palette. Originally, computer graphics displays could only display a certain number of colours at once, due to memory and speed. These colours were called the palette. Originally, graphics adapters were two-colour (black and white). The CGA’s graphics modes could reach a maximum of 4 colours, the EGA gave us an impressive 16, and the VGA a stunning 256 colours all at once. The colours that were displayed by the graphics card were not identified by their actual colour, but instead, by an index number, which referred to one of the colours in the palette. This saved a lot of display space, and still allowed a selection of colours to be used.

The Innovative PNG

The PNG image format was developed as the successor to the GIF format. The original acronym comes from the words “PNG’s Not GIF”, though the format is now best known as the Portable Network Graphics format.

The PNG format was developed in 1995 in response to two major problems with the GIF format. The first, and most immediate problem was that in 1995, Unisys and Compuserve announced that software implementing the GIF image format would be subject to royalties, based on a patent held by Unisys on the LZW compression algorithm used in the GIF format. GIF is technically not free. The second problem with the GIF format was that its feature set was limited, and the need for images with features such as 24 bit colour or 8 bit alpha channels was increasing.

PNG supports a more efficient compression algorithm than GIF, is patent-free, is capable of storing more image formats and includes some nifty error-checking features. When saving identical GIF and PNG images, the resulting PNG file will be 5% to 20% smaller than the GIF file.

From the point of view of a graphic artist, the PNG format is almost identical to the existing GIF format, yet it delivers a better compression rate and supports newer formats that GIF did not support. I now use PNG in every situation in which I would have used GIF in the past.

As the techniques for working with GIF and PNG images is so similar, I will discuss them in this article as if they were one format. The techniques for creating GIF and PNG images are basically the same.

The Space-Age JPEG

JPEG is ideally suited to graphics derived from photographs, as it is very efficient at compressing natural looking images.

JPEG uses a more complex image compression algorithm than GIF and PNG, and requires greater understanding by graphic designers. JPEG is relatively new, compared with loss-less compression such as that used by GIF. The algorithm used to compress JPEG would simply have taken too long to compress or decompress on the earliest computers.

JPEG actually uses a ‘lossy’ algorithm. Rather than recording an image like a computer, it records an image more like a human would describe it. It looks for areas, patterns and colours, rather than simply describing each pixel separately.

The actual compression algorithm is based upon a discrete cosine transform (DCT). This mathematical transform is similar to the algorithms now used in motion picture sound, DVD video, and the common MP3 audio.

What good is a GIF or PNG?

Strengths: Speed, sharpness, solid colour and transparency.

Because the compression algorithm used by GIF and PNG images is a lot simpler than the one used for JPEGs, it takes less time for your computer to decompress and view. With the speed of modern desktop computers, this is no longer the issue it once was.

Because a GIF or PNG’s compression is loss-less, once it has saved there is absolutely no further degradation in image quality or sharpness. The image can be decompressed, edited and re-compressed, and will still be as sharp as the day it was created.

GIF and PNG images thrive on solid, contiguous colours. This is ideal for your corporate logo, or the solid areas and lines in your Website’s navigation. The solid colours will exhibit no ringing, boxing or blurring at all.

GIF and PNG are both capable of binary transparency. Binary transparency allows each pixel in the image to be either completely opaque, or completely transparent. One palette entry of the image is reserved for transparent areas. Instead of showing a particular colour, all instances of that palette index appear invisible, revealing whatever the image is shown in front of. This can be handy when the image is reused in front of a number of different backgrounds on your site. The image can let the background “show through”.

PNG further extends the functionality of GIF. While GIF images are limited to colour palettes of a maximum of 256 colours, PNG supports true colour images. PNG also supports another form of transparency called alpha transparency, in which each pixel can have a colour and a certain amount of transparency, letting the background show through partially in areas. There are some drawbacks to these additional PNG features, however, which will be discussed below.

While support for PNG images in browsers has been low in the past, basic PNG images can now be safely used in all modern browsers, including Microsoft Internet Explorer (4.0b1 and later, Mac and PC), Mozilla, Netscape (6.0 or later), Chimera (2.0 or later), and Safari. Netscape 4.04 supports PNG, but without transparency.

Weaknesses

Virtually all of the weaknesses of the GIF or PNG file format can be attributed to one of two factors: size and palettes.

Size is an obvious disadvantage. The GIF and PNG formats are not good at compressing complex, natural images. Unless an image has been specifically optimised for this format, a very large image can take up 2 to 10 times the space of a JPEG of the same area. This is why GIF and PNG are typically restricted to smaller images on the Web, in addition to images that are particularly suited to the format.

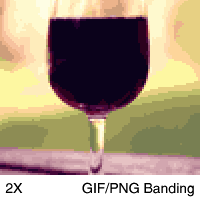

Palettes, when used in a Web image, can actually be of huge benefit. However, if they’re not used well, they can be a nightmare. If the GIF or PNG image contains a smooth gradient or a smooth edge, the graphic designer must divide this area up into a finite number of different colours in order to fit within the limitations of a 256 colour palette. At worst, this could cause excessive artefacts such as dithering or banding.

Incorrect use of the GIF or PNG format. This image has been reduced to 16 colours (no dithering) in order to show the banding artefacts. These artefacts occur when an image that is too complex is saved as a paletted GIF or PNG. The original image has soft gradients, so a JPEG would have been much more suitable here.

It is possible to get around the palette limitation by using features available in the PNG format, which GIF does not support. When creating images for the Web, however, it isn’t yet practical to use either of these two new features of PNG, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the support for PNG in Microsoft’s Internet Explorer browser is buggy, and is not yet capable of showing alpha transparency as it was intended. In addition to this, using a true colour image format or alpha transparency in an image consumes considerably more bandwidth, making it impractical for use over the Internet. At the moment, PNG can be used quite safely with paletted images, just like a GIF.

JPEG At A Glance

Strengths: File size, range of colour.

JPEG is an extremely good format for the compression of natural looking images into a very small size. The quality level of a JPEG can be user-selected when the JPEG is created, allowing for a compromise between file size and image quality.

Because JPEG uses natural colours, rather than a palette, it is very suitable for images that contain smooth or natural colour gradients, textures, and patterns, such as those found in real life. JPEG excels when used for photographs, where the areas of colour are smooth and natural, and blend into each other.

Weaknesses: Compression artefacts, speed and lack of transparency.

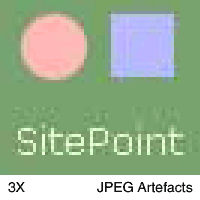

JPEG’s compression isn’t perfect. In fact with some types of images it is far from perfect. As a lossy compression algorithm, there are some compression “artefacts” – slight faults in the decompressed image. If JPEG compression is used correctly, and in the correct circumstances, these artefacts aren’t noticeable at all.

Incorrect use of the JPEG format. This has been magnified 3 times to exaggerate the effect of the JPEG artefacts. Mosquito noise can be seen around the text, and JPEG block noise can be seen inside the blue square. Because of the flat areas of colour, this image should have been compressed using GIF or PNG.

JPEG uses a more sophisticated compression algorithm, and naturally this takes a little more time to compute. This is usually not a problem any more. One other slight disadvantage of JPEG is that it is unable to include transparent areas.

PNG Perfection

If used correctly, a GIF or PNG image will always do what you want it to. First, you have to make sure the image you’re using is suitable for the format.

How to tell if an image is suitable for the GIF or PNG format

When saving an image for the Web, it is better to use a paletted image than a true colour image. This is because each pixel in a paletted image uses at most one third of the bandwidth of a pixel in a true colour image.

This palette has a maximum of 256 colours. Therefore, a good rule of thumb is to look at an image and to try and decide whether it would reduce to 256 colours or less in a favourable manner. When you’re making this decision, remember that any smooth gradients in colour, or smooth edges in shading, will have to be divided up into bands of colour, and each of these bands would take one palette entry. With a little bit of practice, it becomes easy to tell if an image would look good as a GIF or PNG.

If an image is natural, like a photograph, it will have a large number of arbitrary colours. In this case, it is not likely to look good as a GIF or PNG, unless it’s very small.

Try it and see

Remember, whether you output the image as a GIF, PNG or JPEG, you need to ensure that you keep a copy of the uncompressed image. Exporting the image to the GIF, PNG or JPEG format should only occur as the very last step before the image is published, as further editing after this moment is likely to noticeably degrade the quality of the image.

Keeping a copy of the uncompressed image will allow you to re-compress the image in a different format or number of colours later.

Reducing the number of colours

When you save an image in paletted format, your graphics application will require that you reduce the number of colours. Most applications can save the final GIF or PNG with a choice of 256, 16, or 2 colours. Adobe Photoshop’s ‘Save for Web’ feature is ideal for this purpose, as it gives you a great amount of control of your finished file. Photoshop refers to a paletted PNG as ‘PNG-8’ and a true colour PNG as ‘PNG-24’. Choose ‘PNG-8’ or ‘GIF’ compression.

There are two ways to reduce colours in an image. One is a ‘nearest colour’ or ‘no dither’ method, where each part of the image is matched to the nearest colour in the reduced colour palette. The other method is called ‘dithering’ or ‘error diffusion’.

It can be very tempting to use dithering or error diffusion. Error diffusion tends to look quite good in some circumstances. However, the point of error diffusion is to cover up for the inadequacies in the small palette by ‘simulating’ gradients with random (or patterned) noise.

When you’re optimising a GIF or PNG for Web display, the ‘nearest colour’ method should usually be chosen. This creates a smaller file size, and a cleaner looking file. If the image looks too banded using this method, you should consider increasing the size of the palette or using JPEG compression, before you try error diffusion.

Correct use of the GIF or PNG format. Some detail in this image has been lost when we reduce the number of colours to 16. It would probably be best to save this file with more than 16 and less than 256 colours.

Top-down design for GIF or PNG images

If you’re creating an image that you later intend to use in a GIF or PNG file, it is often a good idea to take steps to optimise the image in the creation stage, before you’ve finished creating the image. For example, as you create the image, it’s best to avoid too many textures or gradients. Drop shadows can be used, but for best results, try not to soften the edges of the drop shadow by more than two or three pixels. Try to design using geometric, solid areas rather than soft edges and intricate details.

The Stunning JPEG

For larger and more natural images, JPEG is a great format. It’s flexible and requires a lot less work or forethought than a GIF image. In short, it’s easy to use.

All you need to do to save a JPEG is click on ‘save’ and choose ‘JPEG’.

What’s the level of detail?

Most applications will let you choose a compression level for the JPEG. This is usually found in the same ‘Save As’ dialog box. Again, Photoshop’s ‘Save for Web’ feature is good at this. Select ‘JPEG’ as the compression method. You can change the compression level by using a preset or using the ‘Quality’ slider.

Because JPEG is a lossy compression format, it will reduce some details in the image. The trick to getting the best JPEG on the Web is to get the best compromise between visual image quality and file size. The higher you set the compression level, the lower the quality, and the smaller the file size. A compression level of 10 to 16 usually works well for the Web. In Photoshop, this corresponds to a quality level of around 60 or 70.

Are you sure you’re using the right format?

One of the most common mistakes is to use JPEG for an image that would be more suited to the GIF format. Often, images such as logos, text, graphs, headings or buttons will be constructed using a limited number of solid, sharp areas of colour. If your graphic is as basic as this, and you use the JPEG format, the compression artefacts are likely to become visible in the solid areas of the image, particularly surrounding details and lines. This is sometimes called ‘mosquito noise’ or ‘ringing’, and is certainly not something you want to have appear around your company logo!

If you suspect that the inadequacies of the JPEG format will show up in some of the solid areas of your graphic, try to compress that image using GIF or PNG and see how it compares (both in file size and quality).

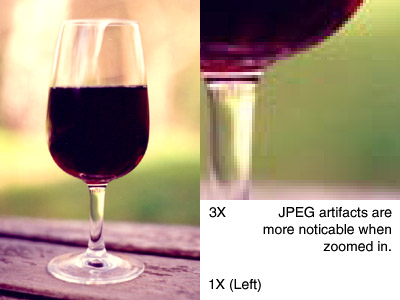

Correct usage of the JPEG format. This image looks reasonable when viewed at normal size, though some mosquito noise and blocking can be seen when we zoom in. Depending on your fussiness, you might like to increase the quality of this JPEG just a little bit.

Inspecting Your Final Image

To fully evaluate your image, after you’ve converted it to GIF, PNG or JPEG, you will need to reload the image in your graphics application to ensure that you are viewing the compressed, final product. Make sure that the computer you’re using is configured to display colours in 24 bits (true colour), so that you can better see actual features of the image.

Zoom up!

Using the zoom tool, look for small details that could be corrected. In a GIF or PNG file, look for banding. If you did use error diffusion, inspect the image areas under a high zoom to ensure that there is no noise in the large, solid areas. Noise should only appear in gradient areas or areas with detail. In a JPEG file, look for ringing artefacts in the solid areas. Remember that a JPEG file has been optimised to look best at 100% zoom, so it is not unusual for degradation in quality to become more obvious when you zoom in further. Inspecting the image closely will give you a good idea about whether the compression should be increased or decreased, but keep in mind that the ringing or mosquito artefacts will not be as obvious when viewed at 100% zoom.

Try other formats

I highly recommend that after you’ve inspected your image in its final compressed form, you go back to the uncompressed image and see if you can try a different format, or number of colours, or quality. To get the best quality and most highly optimised images, I often find myself trying a number of different formats before I’m satisfied.

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve discussed some of the basic concepts of GIF, PNG and JPEG images. There’s a lot more to learn about these formats, such as transparency in GIF and PNG images, matching colours with background or cell colours, and using custom palettes. In addition to this, we can do a few nifty things with PNG that we can’t with GIF.

However, I hope I’ve given a reasonable introduction to optimising GIF, PNG and JPEG images for the Web. Good luck!

Frequently Asked Questions about Image Formats

What are the main differences between GIF, JPEG, and PNG image formats?

The main differences between these three image formats lie in their compression, color depth, and support for transparency. JPEG is a lossy compression format, meaning it discards some image information to reduce file size. It supports millions of colors, making it ideal for photographs. PNG is a lossless compression format, preserving all image data. It supports millions of colors and transparency, making it suitable for complex images and logos. GIF also uses lossless compression, but it only supports 256 colors. It’s best for simple graphics and animations.

How does image compression affect image quality?

Image compression can significantly affect image quality. Lossy compression, like JPEG, discards some image data to reduce file size, which can result in a loss of image quality. On the other hand, lossless compression, like PNG and GIF, preserves all image data, maintaining the original image quality. However, this results in larger file sizes.

When should I use JPEG, PNG, or GIF for my images?

The choice of image format depends on the type of image and its intended use. JPEG is best for photographs and complex images with many colors. PNG is ideal for images that require transparency or have intricate details. GIF is suitable for simple graphics, animations, and images with few colors.

Can I convert one image format to another without losing quality?

Converting from a lossless format like PNG or GIF to a lossy format like JPEG will result in some loss of quality due to the compression. However, converting from JPEG to PNG or GIF should not result in quality loss, although the file size will likely increase.

What is the impact of image format on website performance?

The image format can significantly impact website performance. Larger image files take longer to load, which can slow down your website. Therefore, it’s essential to strike a balance between image quality and file size. JPEG images, due to their lossy compression, tend to have smaller file sizes and load faster, while PNG and GIF images, due to their lossless compression, have larger file sizes but higher quality.

How does image transparency work in PNG and GIF formats?

Both PNG and GIF formats support image transparency, which allows the background of the image to be transparent or semi-transparent. This is particularly useful for logos or images that need to be placed over different backgrounds. However, PNG supports full alpha transparency, allowing for varying degrees of transparency, while GIF only supports binary transparency, meaning pixels are either fully transparent or fully opaque.

What is the role of color depth in image formats?

Color depth refers to the number of colors that an image format can support. JPEG supports 24-bit color depth, meaning it can display millions of colors, while PNG can support up to 48-bit color depth, displaying billions of colors. GIF, on the other hand, only supports 8-bit color depth, limiting it to 256 colors.

How does image interlacing work in PNG and GIF formats?

Interlacing is a method that allows an image to load progressively, meaning a low-quality version of the image loads first, followed by progressively higher-quality versions. This is particularly useful for slower internet connections where it’s better to display a lower quality image quickly than to wait for a high-quality image to load. Both PNG and GIF support interlacing.

Can I animate images in JPEG, PNG, or GIF formats?

Among these three formats, only GIF supports animation. A GIF file can contain multiple images that are displayed in a sequence, creating an animation. Neither JPEG nor PNG support animation.

How does image metadata work in JPEG, PNG, and GIF formats?

Image metadata is information that is stored within an image file. This can include details like the camera settings used to take a photo, the date and time the photo was taken, and copyright information. JPEG supports extensive metadata, while PNG and GIF support limited metadata.

Published in

·CMS & Frameworks·Development Environment·Patterns & Practices·PHP·Programming·Web·August 7, 2014