Write a 3D Soft Engine from Scratch: Part 1

Key Takeaways

- Understanding the basic principles of 3D projection and rendering is crucial before diving into coding a 3D soft engine.

- The tutorial covers the creation of a 3D soft engine using C#, TypeScript, and JavaScript, making it accessible across different programming platforms.

- Key components of a 3D engine include the back buffer, rendering loop, camera, mesh objects, and the device object which handles the rendering logic.

- The device object plays a central role by handling the transformation matrices and projecting 3D coordinates to 2D screen coordinates.

- Practical coding examples are provided for defining cameras and mesh objects, which are essential for creating any 3D scene.

- The tutorial series plans to progressively cover more complex topics such as wireframe rendering, mesh loading, and advanced shading techniques.

- Readers are encouraged to experiment and learn from making adjustments to the provided code examples to better understand the workings of a 3D soft engine.

I’d to like to share with you how I’ve learned to build what’s known as a “3D soft engine” through a series of tutorials. “Software engine” means that we will use only the CPU to build a 3D engine in an old school way (remember Doom on your 80386 ?).

I’ll share with you the C#, TypeScript and JavaScript versions of the code. In this list, you should then find your favorite language or at least something near your favorite one. The idea is to help you transposing the following samples & concepts on your favorite platform. You’ll find the Visual Studio 2012 C#/TS/JS solutions to download at the end also.

So why building a 3D soft engine? Well, it’s simply because it really helps understanding how modern 3D works with our GPUs. Indeed, I’m currently learning the basics of 3D thanks to internal workshops delivered within Microsoft by the awesome David Catuhe. He’s been mastering 3D for many years now and matrices operations is hard-coded in his brain. When I was young, I was dreaming to be able to write such engines but I had the feeling it was too complex for me. Finally, you’ll see that this is not – that – complex. You simply need someone that will help you understanding the underlying principles in a simple way.

Through this series, you will learn how to project some 3D coordinates (X, Y, Z) associated to a point (a vertex) on a 2D screen, how to draw lines between each point, how to fill some triangles, to handle lights, materials and so on. This first tutorial will simply show you how to display 8 points associated to a cube and how to move them in a virtual 3D world.

This tutorial is part of the following series:

1 – Writing the core logic for camera, mesh & device object (this article)

2 – Drawing lines and triangles to obtain a wireframe rendering

3 – Loading meshes exported from Blender in a JSON format

4 – Filling the triangle with rasterization and using a Z-Buffer

4b – Bonus: using tips & parallelism to boost the performance

5 – Handling light with Flat Shading & Gouraud Shading

6 – Applying textures, back-face culling and WebGL

If you’re following the complete series, you will know how to build your own 3D software engine! Your engine will then start by doing some wireframe rendering, then rasterization followed by gouraud shading and lastly by applying textures:

Click on the image to open the final textured rendering in another windows.

By properly following this first tutorial, you’ll learn how to rotate the 8 points of a cube to obtain the following result at the end:

Disclaimer: some of you are wondering why I’m building this 3D software engine rather than using GPU. It’s really for educational purposes. Of course, if you need to build a game with fluid 3D animations, you will need DirectX or OpenGL/WebGL. But once you will have understood how to build a 3D soft engine, more “complex” engine will be simpler to understand. To go further, you definitely should have a look to the BabylonJS WebGL engine built by David Catuhe. More details & tutorials here: Babylon.js: a complete JavaScript framework for building 3D games with HTML 5 and WebGL

Reading prerequisites

I’ve been thinking on how to write these tutorials for a long time now. And I’ve finally decided not to explain each required principle myself. There is a lot of good resources on the web that will explain those important principles better than I. But I’ve then spent quite some time browsing the web for you to choose, according to myself, the best one to read:

– World, View and Projection Matrix Unveiled

– Tutorial 3 : Matrices that will provide you an introduction to matrices, the model, view & projection matrices.

– Cameras on OpenGL ES 2.x – The ModelViewProjection Matrix : this one is really interesting also as it explains the story starting by how cameras and lenses work.

– Transforms (Direct3D 9)

– A brief introduction to 3D: an excellent PowerPoint slides deck ! Read at least up to slide 27. After that, it’s too linked to a technology talking to GPU (OpenGL or DirectX).

– OpenGL Transformation

Read those articles by not focusing on the technology associated (like OpenGL or DirectX) or on the concept of triangles you may have seen in the figures. We will see that later on.

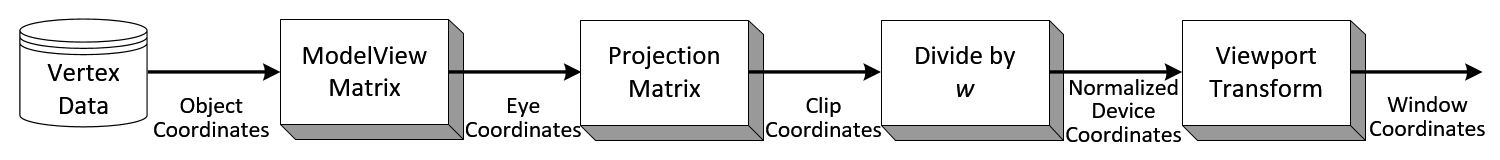

By reading those articles, you really need to understand that there is a series of transformations done that way:

– we start by a 3D object centered on itself

– the same object is then moved into the virtual 3D world by translation, scaling or rotation operations via matrices

– a camera will look at this 3D object positioned in the 3D world

– the final projection of all that will be done into a 2D space which is your screen

All this magic is done by cumulating transformations through matrices operations. You should really be at least a bit familiar with those concepts before running through these tutorials. Even if you don’t understand everything by reading them the first time. You should read them first. You will probably go back to those articles later on while writing your own version of this 3D soft engine. This is completely normal, don’t worry! ;) The best way to learn 3D if by experimenting and doing mistakes.

We won’t neither spend some times on how matrix operations works. The good news is that you don’t really need to understand matrices. Simply view it as a black box doing the right operations for you. I’m not a master of matrices but I’ve managed to write a 3D soft engine by myself. So you should also succeed in doing so.

We will then use libraries that will do the job for us: SharpDX, a managed wrapper on top of DirectX, for C# developers and babylon.math.js written by David Catuhe for JavaScript developers. I’ve rewritten it in TypeScript also.

Software prerequisites

We will write a WinRT/XAML Windows Store Apps in C# and/or a HTML5 application with TypeScript/JavaScript. So if you want to use the C# samples as-is, you need to install:

1 – Windows 8

2 – Visual Studio 2012 Express for Windows Store Apps. You can download it for free: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-US/windows/apps/br211386

If you choose to use the TypeScript samples, you need to install it from: https://www.typescriptlang.org/#Download . All samples have been updated and tested successfully with TypeScript 0.9.

You will find the plug-in for Visual Studio 2012 but there are other options available: Sublime Text, Vi, Emacs: TypeScript enabled! On my side, I’ve learned TypeScript by porting the C# version of my code to TypeScript. If you’re also interested in learning TypeScript, a first good introduction is this webcast: Anders Hejlsberg: Introducing TypeScript . Please install also Web Essentials 2012 which had a full support for TypeScript preview and compilation.

If you choose JavaScript, you just need your favorite IDE and a HTML5 compatible browser. :)

Please create a project named “SoftEngine” targeting the language you’d like to use. If it’s C#, add the “SharpDX core assembly” by using NuGet on your solution:

If it’s TypeScript, download babylon.math.ts. If’ it’s JavaScript download babylon.math.js. Add a reference to those files in both cases.

Back buffer & rendering loop

In a 3D engine, we’re rendering the complete scene during each frame with the hope of keeping an optimal 60 frames per second (FPS) to keep fluid animations. To do our rendering job, we need what we call a back buffer. This could be seen as 2 dimensional array mapping the screen/window size. Every cell of the array is mapped to a pixel on the screen.

In our XAML Windows Store Apps, we will use a byte[] array that will act as our dynamic back buffer. For every frame being rendered in the animation loop (tick), this buffer will be affected to a WriteableBitmap acting as the source of a XAML image control that will be called the front buffer. For the rendering loop, we’re going to ask to the XAML rendering engine to call us for every frame it will generate. The registration is done thanks to this line of code:

CompositionTarget.Rendering += CompositionTarget_Rendering;

In HTML5, we’re going to use of course the <canvas /> element. The canvas element has already a back buffer data array associated to it. You can access it through the getImageData() and setImageData() functions. The animation loop will be handled by the requestAnimationFrame() function. This one is much more efficient that an equivalent of a setTimeout(function() {], 1000/60) as it’s handled natively by the browser that will callback our code only when it will be ready to draw.

Note: in both cases, you can render the frames in a different resolution that the actual width & height of the final window. For instance, you can have a back buffer of 640×480 pixels whereas the final display screen (front buffer) will be in 1920×1080. In XAML and thanks to CSS in HTML5, you will then benefit from “hardware scaling”. The rendering engines of XAML and of the browser will stretch the back buffer data to the front buffer window by even using an anti-aliasing algorithm. In both cases, this task is done by the GPU. This is why we call it “hardware scaling” (hardware is the GPU). You can read more about this topic addressed in HTML5 here: Unleash the power of HTML 5 Canvas for gaming . This approach is often used in games for instance to boost the performance as you have less pixels to address.

Camera & Mesh objects

Let’s start coding. First, we need to define some objects that will embed the details needed for a camera and for a mesh. A mesh is a cool name to describe a 3D object.

Our Camera will have 2 properties: its position in the 3D world and where it’s looking at, the target. Both are made of 3D coordinates named a Vector3. C# will use SharpDX.Vector3 and TypeScript & JavaScript will use BABYLON.Vector3.

Our Mesh will have a collection of vertices (several vertex or 3D points) that will be used to build our 3D object, its position in the 3D world and its rotation state. To identify it, it will also have a name.

To resume, we need the following code:

// Camera.cs & Mesh.cs using SharpDX; namespace SoftEngine public class Camera { public Vector3 Position { get; set; } public Vector3 Target { get; set; } } public class Mesh { public string Name { get; set; } public Vector3[] Vertices { get; private set; } public Vector3 Position { get; set; } public Vector3 Rotation { get; set; } public Mesh(string name, int verticesCount) { Vertices = new Vector3[verticesCount]; Name = name; } }

//<reference path="babylon.math.ts"/> module SoftEngine { export class Camera { Position: BABYLON.Vector3; Target: BABYLON.Vector3; constructor() { this.Position = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); this.Target = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); } } export class Mesh { Position: BABYLON.Vector3; Rotation: BABYLON.Vector3; Vertices: BABYLON.Vector3[]; constructor(public name: string, verticesCount: number) { this.Vertices = new Array(verticesCount); this.Rotation = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); this.Position = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); } }

var SoftEngine; function (SoftEngine) { var Camera = (function () { function Camera() { this.Position = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); this.Target = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); } return Camera; })(); SoftEngine.Camera = Camera; var Mesh = (function () { function Mesh(name, verticesCount) { this.name = name; this.Vertices = new Array(verticesCount); this.Rotation = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); this.Position = BABYLON.Vector3.Zero(); } return Mesh; })(); SoftEngine.Mesh = Mesh; )(SoftEngine || (SoftEngine = {}));

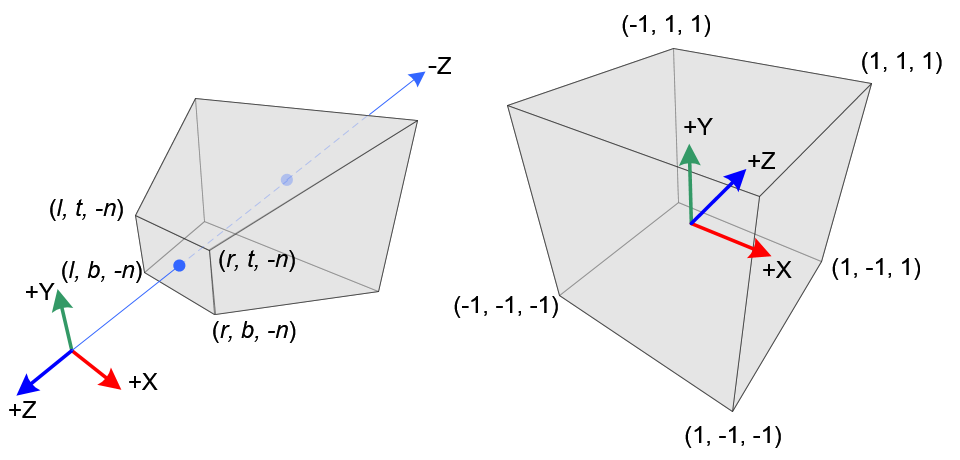

For instance, if you want to describe a cube using our Mesh object, you need to create 8 vertices associated to the 8 points of the cube. Here are the coordinates on a cube displayed in Blender:

With a left-handed world. Remember also that when you’re creating a mesh, the coordinates system is starting at the center of the mesh. So, X=0, Y=0, Z=0 is the center of the cube.

This could be created via this kind of code:

var mesh = new Mesh("Cube", 8); esh.Vertices[0] = new Vector3(-1, 1, 1); esh.Vertices[1] = new Vector3(1, 1, 1); esh.Vertices[2] = new Vector3(-1, -1, 1); esh.Vertices[3] = new Vector3(-1, -1, -1); esh.Vertices[4] = new Vector3(-1, 1, -1); esh.Vertices[5] = new Vector3(1, 1, -1); esh.Vertices[6] = new Vector3(1, -1, 1); esh.Vertices[7] = new Vector3(1, -1, -1);

The most important part: the Device object

Now that we have our basic objects and we know how to build 3D meshes, we need the most important part: the Device object. It’s the core of our 3D engine.

In it’s rendering function, we will build the view matrix and the projection matrix based on the camera we will have defined before.

Then, we will iterate through each available mesh to build their associated world matrix based on their current rotation and translation values. Finally, once done, the final transformation matrix to apply is:

var transformMatrix = worldMatrix * viewMatrix * projectionMatrix;

This is the concept you absolutely need to understand by reading the previous prerequisites resources. Otherwise, you will probably simply copy/paste the code without understanding anything about the magic underneath. This is not a very big problem for further tutorials but again, it’s better to know what’s you’re coding.

Using this transformation matrix, we’re going to project each vertex of each mesh in the 2D world to obtain X,Y coordinates from their X,Y,Z coordinates. To finally draw on screen, we’re adding a small clip logic to only display visible pixels via a PutPixel method/function.

Here are the various versions of the Device object. I’ve tried to comment the code to help you understanding it as much as possible.

Note: Microsoft Windows is drawing using the BGRA color space (Blue, Green, Red, Alpha) whereas the HTML5 canvas is drawing using the RGBA (Red, Green, Blue, Alpha) color space. That’s why, you will notice some slight differences in the code between C# and HTML5.

using Windows.UI.Xaml.Media.Imaging; using System.Runtime.InteropServices.WindowsRuntime; using SharpDX; namespace SoftEngine public class Device { private byte[] backBuffer; private WriteableBitmap bmp; public Device(WriteableBitmap bmp) { this.bmp = bmp; // the back buffer size is equal to the number of pixels to draw // on screen (width*height) * 4 (R,G,B & Alpha values). backBuffer = new byte[bmp.PixelWidth * bmp.PixelHeight * 4]; } // This method is called to clear the back buffer with a specific color public void Clear(byte r, byte g, byte b, byte a) { for (var index = 0; index < backBuffer.Length; index += 4) { // BGRA is used by Windows instead by RGBA in HTML5 backBuffer[index] = b; backBuffer[index + 1] = g; backBuffer[index + 2] = r; backBuffer[index + 3] = a; } } // Once everything is ready, we can flush the back buffer // into the front buffer. public void Present() { using (var stream = bmp.PixelBuffer.AsStream()) { // writing our byte[] back buffer into our WriteableBitmap stream stream.Write(backBuffer, 0, backBuffer.Length); } // request a redraw of the entire bitmap bmp.Invalidate(); } // Called to put a pixel on screen at a specific X,Y coordinates public void PutPixel(int x, int y, Color4 color) { // As we have a 1-D Array for our back buffer // we need to know the equivalent cell in 1-D based // on the 2D coordinates on screen var index = (x + y * bmp.PixelWidth) * 4; backBuffer[index] = (byte)(color.Blue * 255); backBuffer[index + 1] = (byte)(color.Green * 255); backBuffer[index + 2] = (byte)(color.Red * 255); backBuffer[index + 3] = (byte)(color.Alpha * 255); } // Project takes some 3D coordinates and transform them // in 2D coordinates using the transformation matrix public Vector2 Project(Vector3 coord, Matrix transMat) { // transforming the coordinates var point = Vector3.TransformCoordinate(coord, transMat); // The transformed coordinates will be based on coordinate system // starting on the center of the screen. But drawing on screen normally starts // from top left. We then need to transform them again to have x:0, y:0 on top left. var x = point.X * bmp.PixelWidth + bmp.PixelWidth / 2.0f; var y = -point.Y * bmp.PixelHeight + bmp.PixelHeight / 2.0f; return (new Vector2(x, y)); } // DrawPoint calls PutPixel but does the clipping operation before public void DrawPoint(Vector2 point) { // Clipping what's visible on screen if (point.X >= 0 && point.Y >= 0 && point.X < bmp.PixelWidth && point.Y < bmp.PixelHeight) { // Drawing a yellow point PutPixel((int)point.X, (int)point.Y, new Color4(1.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f)); } } // The main method of the engine that re-compute each vertex projection // during each frame public void Render(Camera camera, params Mesh[] meshes) { // To understand this part, please read the prerequisites resources var viewMatrix = Matrix.LookAtLH(camera.Position, camera.Target, Vector3.UnitY); var projectionMatrix = Matrix.PerspectiveFovRH(0.78f, (float)bmp.PixelWidth / bmp.PixelHeight, 0.01f, 1.0f); foreach (Mesh mesh in meshes) { // Beware to apply rotation before translation var worldMatrix = Matrix.RotationYawPitchRoll(mesh.Rotation.Y,

mesh.Rotation.X, mesh.Rotation.Z) * Matrix.Translation(mesh.Position); var transformMatrix = worldMatrix * viewMatrix * projectionMatrix; foreach (var vertex in mesh.Vertices) { // First, we project the 3D coordinates into the 2D space var point = Project(vertex, transformMatrix); // Then we can draw on screen DrawPoint(point); } } } }

///<reference path="babylon.math.ts"/> module SoftEngine { export class Device { // the back buffer size is equal to the number of pixels to draw // on screen (width*height) * 4 (R,G,B & Alpha values). private backbuffer: ImageData; private workingCanvas: HTMLCanvasElement; private workingContext: CanvasRenderingContext2D; private workingWidth: number; private workingHeight: number; // equals to backbuffer.data private backbufferdata; constructor(canvas: HTMLCanvasElement) { this.workingCanvas = canvas; this.workingWidth = canvas.width; this.workingHeight = canvas.height; this.workingContext = this.workingCanvas.getContext("2d"); } // This function is called to clear the back buffer with a specific color public clear(): void { // Clearing with black color by default this.workingContext.clearRect(0, 0, this.workingWidth, this.workingHeight); // once cleared with black pixels, we're getting back the associated image data to // clear out back buffer this.backbuffer = this.workingContext.getImageData(0, 0, this.workingWidth, this.workingHeight); } // Once everything is ready, we can flush the back buffer // into the front buffer. public present(): void { this.workingContext.putImageData(this.backbuffer, 0, 0); } // Called to put a pixel on screen at a specific X,Y coordinates public putPixel(x: number, y: number, color: BABYLON.Color4): void { this.backbufferdata = this.backbuffer.data; // As we have a 1-D Array for our back buffer // we need to know the equivalent cell index in 1-D based // on the 2D coordinates of the screen var index: number = ((x >> 0) + (y >> 0) * this.workingWidth) * 4; // RGBA color space is used by the HTML5 canvas this.backbufferdata[index] = color.r * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 1] = color.g * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 2] = color.b * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 3] = color.a * 255; } // Project takes some 3D coordinates and transform them // in 2D coordinates using the transformation matrix public project(coord: BABYLON.Vector3, transMat: BABYLON.Matrix): BABYLON.Vector2 { // transforming the coordinates var point = BABYLON.Vector3.TransformCoordinates(coord, transMat); // The transformed coordinates will be based on coordinate system // starting on the center of the screen. But drawing on screen normally starts // from top left. We then need to transform them again to have x:0, y:0 on top left. var x = point.x * this.workingWidth + this.workingWidth / 2.0 >> 0; var y = -point.y * this.workingHeight + this.workingHeight / 2.0 >> 0; return (new BABYLON.Vector2(x, y)); } // drawPoint calls putPixel but does the clipping operation before public drawPoint(point: BABYLON.Vector2): void { // Clipping what's visible on screen if (point.x >= 0 && point.y >= 0 && point.x < this.workingWidth

&& point.y < this.workingHeight) { // Drawing a yellow point this.putPixel(point.x, point.y, new BABYLON.Color4(1, 1, 0, 1)); } } // The main method of the engine that re-compute each vertex projection // during each frame public render(camera: Camera, meshes: Mesh[]): void { // To understand this part, please read the prerequisites resources var viewMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.LookAtLH(camera.Position, camera.Target, BABYLON.Vector3.Up()); var projectionMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.PerspectiveFovLH(0.78,

this.workingWidth / this.workingHeight, 0.01, 1.0); for (var index = 0; index < meshes.length; index++) { // current mesh to work on var cMesh = meshes[index]; // Beware to apply rotation before translation var worldMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.RotationYawPitchRoll( cMesh.Rotation.y, cMesh.Rotation.x, cMesh.Rotation.z) .multiply(BABYLON.Matrix.Translation( cMesh.Position.x, cMesh.Position.y, cMesh.Position.z)); var transformMatrix = worldMatrix.multiply(viewMatrix).multiply(projectionMatrix); for (var indexVertices = 0; indexVertices < cMesh.Vertices.length; indexVertices++) { // First, we project the 3D coordinates into the 2D space var projectedPoint = this.project(cMesh.Vertices[indexVertices], transformMatrix); // Then we can draw on screen this.drawPoint(projectedPoint); } } } }

var SoftEngine; function (SoftEngine) { var Device = (function () { function Device(canvas) { // Note: the back buffer size is equal to the number of pixels to draw // on screen (width*height) * 4 (R,G,B & Alpha values). this.workingCanvas = canvas; this.workingWidth = canvas.width; this.workingHeight = canvas.height; this.workingContext = this.workingCanvas.getContext("2d"); } // This function is called to clear the back buffer with a specific color Device.prototype.clear = function () { // Clearing with black color by default this.workingContext.clearRect(0, 0, this.workingWidth, this.workingHeight); // once cleared with black pixels, we're getting back the associated image data to // clear out back buffer this.backbuffer = this.workingContext.getImageData(0, 0, this.workingWidth, this.workingHeight); }; // Once everything is ready, we can flush the back buffer // into the front buffer. Device.prototype.present = function () { this.workingContext.putImageData(this.backbuffer, 0, 0); }; // Called to put a pixel on screen at a specific X,Y coordinates Device.prototype.putPixel = function (x, y, color) { this.backbufferdata = this.backbuffer.data; // As we have a 1-D Array for our back buffer // we need to know the equivalent cell index in 1-D based // on the 2D coordinates of the screen var index = ((x >> 0) + (y >> 0) * this.workingWidth) * 4; // RGBA color space is used by the HTML5 canvas this.backbufferdata[index] = color.r * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 1] = color.g * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 2] = color.b * 255; this.backbufferdata[index + 3] = color.a * 255; }; // Project takes some 3D coordinates and transform them // in 2D coordinates using the transformation matrix Device.prototype.project = function (coord, transMat) { var point = BABYLON.Vector3.TransformCoordinates(coord, transMat); // The transformed coordinates will be based on coordinate system // starting on the center of the screen. But drawing on screen normally starts // from top left. We then need to transform them again to have x:0, y:0 on top left. var x = point.x * this.workingWidth + this.workingWidth / 2.0 >> 0; var y = -point.y * this.workingHeight + this.workingHeight / 2.0 >> 0; return (new BABYLON.Vector2(x, y)); }; // drawPoint calls putPixel but does the clipping operation before Device.prototype.drawPoint = function (point) { // Clipping what's visible on screen if (point.x >= 0 && point.y >= 0 && point.x < this.workingWidth

&& point.y < this.workingHeight) { // Drawing a yellow point this.putPixel(point.x, point.y, new BABYLON.Color4(1, 1, 0, 1)); } }; // The main method of the engine that re-compute each vertex projection // during each frame Device.prototype.render = function (camera, meshes) { // To understand this part, please read the prerequisites resources var viewMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.LookAtLH(camera.Position, camera.Target, BABYLON.Vector3.Up()); var projectionMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.PerspectiveFovLH(0.78,

this.workingWidth / this.workingHeight, 0.01, 1.0); for (var index = 0; index < meshes.length; index++) { // current mesh to work on var cMesh = meshes[index]; // Beware to apply rotation before translation var worldMatrix = BABYLON.Matrix.RotationYawPitchRoll( cMesh.Rotation.y, cMesh.Rotation.x, cMesh.Rotation.z) .multiply(BABYLON.Matrix.Translation( cMesh.Position.x, cMesh.Position.y, cMesh.Position.z)); var transformMatrix = worldMatrix.multiply(viewMatrix).multiply(projectionMatrix); for (var indexVertices = 0; indexVertices < cMesh.Vertices.length; indexVertices++) { // First, we project the 3D coordinates into the 2D space var projectedPoint = this.project(cMesh.Vertices[indexVertices], transformMatrix); // Then we can draw on screen this.drawPoint(projectedPoint); } } }; return Device; })(); SoftEngine.Device = Device; )(SoftEngine || (SoftEngine = {}));

Putting it all together

We finally need to create a mesh (our cube), create a camera and target our mesh & instantiate our Device object.

Once done, we will launch the animation/rendering loop. In optimal cases, this loop will be called every 16ms (60 FPS). During each tick (call to the handler registered to the rendering loop), we will launch the following logic every time:

1 – Clear the screen and all associated pixels with black ones (Clear() function)

2 – Update the various position & rotation values of our meshes

3 – Render them into the back buffer by doing the required matrix operations (Render() function)

4 – Display them on screen by flushing the back buffer data into the front buffer (Present() function)

private Device device; Mesh mesh = new Mesh("Cube", 8); Camera mera = new Camera(); private void Page_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e) // Choose the back buffer resolution here WriteableBitmap bmp = new WriteableBitmap(640, 480); device = new Device(bmp); // Our XAML Image control frontBuffer.Source = bmp; mesh.Vertices[0] = new Vector3(-1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[1] = new Vector3(1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[2] = new Vector3(-1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[3] = new Vector3(-1, -1, -1); mesh.Vertices[4] = new Vector3(-1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[5] = new Vector3(1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[6] = new Vector3(1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[7] = new Vector3(1, -1, -1); mera.Position = new Vector3(0, 0, 10.0f); mera.Target = Vector3.Zero; // Registering to the XAML rendering loop CompositionTarget.Rendering += CompositionTarget_Rendering; // Rendering loop handler void CompositionTarget_Rendering(object sender, object e) device.Clear(0, 0, 0, 255); // rotating slightly the cube during each frame rendered mesh.Rotation = new Vector3(mesh.Rotation.X + 0.01f, mesh.Rotation.Y + 0.01f, mesh.Rotation.Z); // Doing the various matrix operations device.Render(mera, mesh); // Flushing the back buffer into the front buffer device.Present();

///<reference path="SoftEngine.ts"/> var canvas: HTMLCanvasElement; var device: SoftEngine.Device; var mesh: SoftEngine.Mesh; var meshes: SoftEngine.Mesh[] = []; var mera: SoftEngine.Camera; document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", init, false); function init() { canvas = <HTMLCanvasElement> document.getElementById("frontBuffer"); mesh = new SoftEngine.Mesh("Cube", 8); meshes.push(mesh); mera = new SoftEngine.Camera(); device = new SoftEngine.Device(canvas); mesh.Vertices[0] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[1] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[2] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[3] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, -1, -1); mesh.Vertices[4] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[5] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[6] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[7] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, -1, -1); mera.Position = new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 0, 10); mera.Target = new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 0, 0); // Calling the HTML5 rendering loop requestAnimationFrame(drawingLoop); // Rendering loop handler function drawingLoop() { device.clear(); // rotating slightly the cube during each frame rendered mesh.Rotation.x += 0.01; mesh.Rotation.y += 0.01; // Doing the various matrix operations device.render(mera, meshes); // Flushing the back buffer into the front buffer device.present(); // Calling the HTML5 rendering loop recursively requestAnimationFrame(drawingLoop);

var canvas; var device; var mesh; var meshes = []; var mera; document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", init, false); function init() { canvas = document.getElementById("frontBuffer"); mesh = new SoftEngine.Mesh("Cube", 8); meshes.push(mesh); mera = new SoftEngine.Camera(); device = new SoftEngine.Device(canvas); mesh.Vertices[0] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[1] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, 1, 1); mesh.Vertices[2] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[3] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, -1, -1); mesh.Vertices[4] = new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[5] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, 1, -1); mesh.Vertices[6] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, -1, 1); mesh.Vertices[7] = new BABYLON.Vector3(1, -1, -1); mera.Position = new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 0, 10); mera.Target = new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 0, 0); // Calling the HTML5 rendering loop requestAnimationFrame(drawingLoop); // Rendering loop handler function drawingLoop() { device.clear(); // rotating slightly the cube during each frame rendered mesh.Rotation.x += 0.01; mesh.Rotation.y += 0.01; // Doing the various matrix operations device.render(mera, meshes); // Flushing the back buffer into the front buffer device.present(); // Calling the HTML5 rendering loop recursively requestAnimationFrame(drawingLoop);

If you’ve managed to follow properly this first tutorial, you should obtain something like that:

If not, download the solutions containing the source code:

– C# : SoftEngineCSharpPart1.zip

– TypeScript : SoftEngineTSPart1.zip

– JavaScript : SoftEngineJSPart1.zip or simply right-click –> view source on the embedded iframe

Simply review the code and try to find what’s wrong with yours. :)

In the next tutorial, we’re going to learn how to draw lines between each vertex & the concept of faces/triangles to obtain something like that:

See you in the second part of this series.

Originally published: https://blogs.msdn.com/b/davrous/archive/2013/06/13/tutorial-series-learning-how-to-write-a-3d-soft-engine-from-scratch-in-c-typescript-or-javascript.aspx. Reprinted here with permission of the author.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Writing a 3D Soft Engine from Scratch

What are the basic concepts I need to understand before starting to write a 3D soft engine from scratch?

Before you start writing a 3D soft engine from scratch, you need to understand some basic concepts. These include understanding the Cartesian coordinate system, which is used to represent 3D objects in a 2D space. You also need to understand vectors, which are used to represent direction and magnitude in 3D space. Other important concepts include understanding how to perform transformations such as scaling, rotation, and translation on 3D objects, and understanding the concept of a camera in a 3D space.

How do I start developing a 3D game engine?

Developing a 3D game engine from scratch can be a complex task, but it can be broken down into several steps. First, you need to decide on the programming language you will use. C++ is a popular choice due to its performance and flexibility, but other languages like Java or Rust can also be used. Next, you need to understand the basic concepts of 3D graphics, such as vectors, matrices, and transformations. Then, you can start implementing basic features such as rendering 3D objects, handling user input, and managing game states. As you progress, you can add more advanced features like physics, lighting, and AI.

What are the challenges I might face when writing a 3D soft engine from scratch?

Writing a 3D soft engine from scratch can be a challenging task. One of the main challenges is the complexity of 3D mathematics. Understanding and implementing concepts like vectors, matrices, and transformations can be difficult. Another challenge is performance. Rendering 3D graphics requires a lot of computational power, so you need to write efficient code to ensure your engine runs smoothly. Finally, debugging can be difficult, as errors in your code can result in subtle visual glitches that are hard to track down.

How can I optimize the performance of my 3D soft engine?

There are several ways to optimize the performance of your 3D soft engine. One way is to use efficient data structures and algorithms. For example, using a spatial partitioning data structure like an octree can help you quickly determine which objects are visible and need to be rendered. Another way is to use hardware acceleration. Modern GPUs are designed to perform 3D calculations quickly, so you can offload some of the work from the CPU to the GPU. Finally, you can use techniques like frustum culling and level of detail to reduce the amount of work your engine needs to do.

Can I write a 3D soft engine using a language other than C++?

Yes, you can write a 3D soft engine using a variety of programming languages. While C++ is a popular choice due to its performance and flexibility, other languages like Java, Rust, and Python can also be used. The choice of language depends on your personal preference and the requirements of your project. For example, if you want to develop a web-based game, you might choose to use JavaScript or WebGL. If you’re more comfortable with Python, you might choose to use a library like Pygame or Panda3D.

What resources can I use to learn more about 3D graphics programming?

There are many resources available to help you learn about 3D graphics programming. Online tutorials and articles can provide a good introduction to the basics. Books like “Real-Time Rendering” by Tomas Akenine-Möller and “Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice” by James D. Foley provide a more in-depth look at the subject. There are also many online forums and communities where you can ask questions and get help from experienced developers.

How long does it take to write a 3D soft engine from scratch?

The time it takes to write a 3D soft engine from scratch can vary greatly depending on your experience level, the complexity of the engine, and the amount of time you can dedicate to the project. For a simple engine, it might take a few months. For a more complex engine, it could take several years. It’s important to start with a clear plan and set realistic goals for your project.

Can I use a 3D soft engine to create a game?

Yes, a 3D soft engine can be used to create a game. In fact, many popular games are built using custom 3D engines. However, creating a game requires more than just a 3D engine. You also need to create or import 3D models, design levels, implement game mechanics, and more. If you’re new to game development, you might find it easier to start with a game engine like Unity or Unreal Engine, which provide a lot of tools and resources to help you create a game.

What is the difference between a 3D soft engine and a game engine?

A 3D soft engine is a software that is responsible for rendering 3D graphics. It takes 3D models and textures as input and produces a 2D image as output. A game engine, on the other hand, is a more comprehensive software that includes a 3D engine as well as other components necessary for game development, such as physics engine, audio engine, input handling, and more.

Can I write a 3D soft engine from scratch if I’m a beginner in programming?

Writing a 3D soft engine from scratch can be a challenging task, especially for beginners. It requires a good understanding of programming concepts and 3D mathematics. However, it’s not impossible. If you’re willing to put in the time and effort to learn, you can definitely write your own 3D soft engine. Start by learning a programming language, then move on to learning about 3D graphics. There are many resources available online to help you along the way.

David Rousset is a Senior Program Manager at Microsoft, in charge of driving adoption of HTML5 standards. He has been a speaker at several famous web conferences such as Paris Web, CodeMotion, ReasonsTo or jQuery UK. He’s the co-author of the WebGL Babylon.js open-source engine. Read his blog on MSDN or follow him on Twitter.

Published in

·automation·Cloud·Debugging & Deployment·Meta·Open Source·PHP·Programming·Web·July 19, 2014