Keeping The Community In The Java Community Process (JCP)

It’s Open Source Week at SitePoint! All week we’re publishing articles focused on everything Open Source, Free Software and Community, so keep checking the OSW tag for the latest updates.

Java is over twenty years old and is consistently rated as one of the most popular programming language on the planet. Part of what makes Java so appealing to developers is the way that features evolve in a controlled way that rarely has any impact on backwards compatibility. The way Java evolves has had a somewhat varied history, especially with respect to open source. In this article we’ll look at how the Java platform is standardised whilst maintaining community involvement through the Java Community Process (JCP). We’ll also see some of the challenges that process has faced and still faces today.

Key Takeaways

- The Java Community Process (JCP) was created by Sun as a new standards body to develop Java specifications, maintaining a balance between a single company’s total control and a completely open process where all parties have an equal say.

- The JCP is made up of interested parties contributing ideas for Java’s development, and its structure includes Executive Committees (EC) responsible for approving the passage of specifications. The EC is made up of 16 ratified seats, 6 elected seats, 2 associate seats, and 1 permanent seat for Oracle America.

- Any full member of the JCP can submit a Java Specification Request (JSR) which, if accepted, begins the process of developing a standard. An Expert Group (EG) is formed from full JCP members or member representatives to develop the specification, which is then published for public review before the JCP membership votes for its approval.

- Despite the JCP’s success, it still faces challenges, particularly in the areas of Java ME, Java SE and Java EE. However, the JCP’s focus on community and recent changes to the JCP membership agreement are steps in the right direction to ensure that Java standards remain open and continue to evolve to meet the needs of developers.

Before the JCP

After its launch, Java rapidly gained popularity and numerous corporations, both big and small, wanted to be part of this exciting new software platform. In the early days, IBM quickly got involved through Taligent – a joint venture between IBM and Apple, which started out developing an object-oriented application framework. Taligent also had strengths in internationalisation and contributed a number of classes to JDK 1.1 (like the java.text package and the java.util.Calendar class).

Microsoft became a Java licensee as well, integrating it into early versions of Internet Explorer. Microsoft’s implementation caused a lot of trouble, resulting in a long and protracted lawsuit over how Microsoft broke the terms of their license agreement. This was ultimately settled in Sun’s favour but was essentially what prompted the development of C#.

Around 1997 there was a lot of pressure on Sun Microsystems to hand over the standardisation of Java to a well know international standards body such as ANSI or the ECMA. Sun was not keen to do this for two reasons. Primarily, it would give control of the Java platform to other people and Sun realised the value of Java to them, certainly in terms of marketing if not in pure revenue.

The second reason was more about how quickly Java could evolve over time. Standardisation processes can be classified on a spectrum where one end is a single company with total control and the other is a completely open process where all involved parties have an equal say. Each of these has strengths, but also weaknesses. If Sun continued to control the development of Java alone, developers would simply have to accept whatever Sun’s product management deemed to be the best features. If Sun handed Java over to someone like ANSI the speed of development would be impacted. Open, international standards bodies are notoriously slow in developing and ratifying standards (ANSI has only managed to produce three revisions of the C standard in the last 26 years!)

The Java Community Process

Sun’s management decided that the best way to develop the specifications for Java was to create a new standards body whose processes would be somewhere between the two ends of the spectrum. Having released an initial proposal in October, Sun officially launched the Java Community Process (JCP) on December 8th, 1998, which was the same day it released JDK 1.2. It also took this opportunity to rebrand Java as Java 2 and introduced the concept of different ”editions”, specifically:

- Java 2 Micro Edition (J2ME) for mobile and embedded devices

- Java 2 Standard Edition (J2SE) covering the language, core libraries and JVM

- Java 2 Enterprise Edition (J2EE) for enterprise applications using components like servlets and Enterprise Java Beans (EJBs) in an application server container (who says microservices are new?)

The JCP’s Structure

The JCP would be made up of parties interested in contributing ideas for how Java could be developed. Initially, membership was restricted only to corporations but that was later changed to include Java User Groups, academics and even individuals.

Fortunately, Sun realised the key word in the name of the JCP was Community.

The original structure of the JCP had two Executive Committees (EC), whose role was to approve the passage of specifications through key points of the process. One EC was responsible for J2ME and another for J2SE and J2EE. In August 2012 these were merged into a single EC for all Java standardisation activities.

Today, under JCP rules Version 2.10 the EC is formed of the following:

- 16 ratified seats

- 6 elected seats

- 2 associate seats

- 1 permanent seat for Oracle America

Members serve 2-year terms that are staggered so that 12 of the 24 seats are normally up for ratification or election each year. The latest version of the JCP charter also removed the requirement for membership fees. The current goal is clearly to increase membership and therefore participation from the community.

Changing Java through the JCP

Any full member of the Java Community Process can submit a Java Specification Request (JSR), which consists of a variety of information about the proposed specification including a description of what it will standardise, estimated dates for development and why it is required. The EC votes on the JSR and, if accepted, the process of developing the standard begins.

To do this an Expert Group (EG) is formed from full JCP members or member representatives who are interested in helping to develop the specification. The specification lead (typically the person who submitted the JSR, but this can change over time) decides who to accept for the EG. Once the EG has created the specification it is published for public review before the JCP membership votes for its approval.

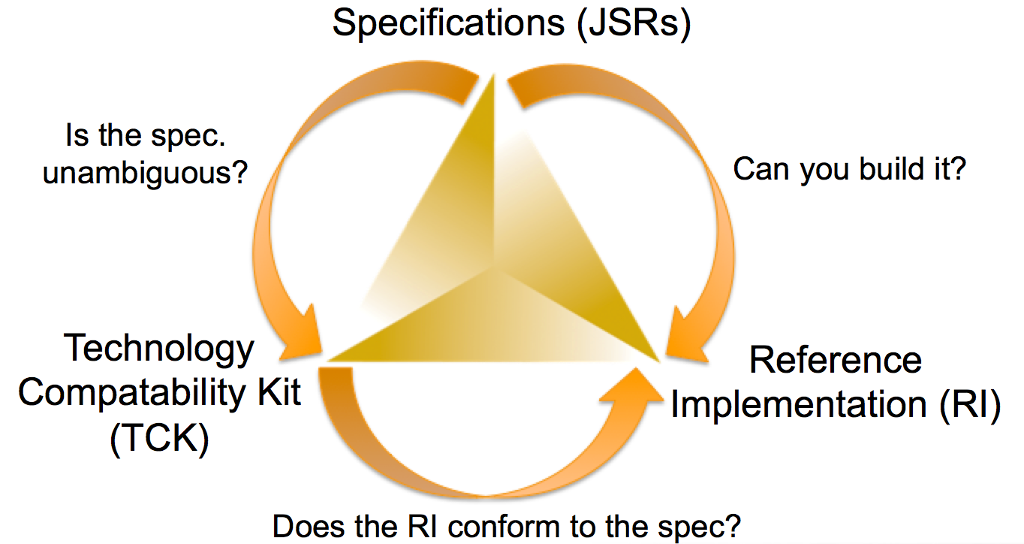

The deliverables of a JSR consist of three parts and make up the “golden triangle” of the JCP:

- The formal specification

- A Reference Implementation (RI) of the specification

- A Test Compatibility Kit (TCK)

The diagram below shows the relationship of these three parts.

Initially, the JCP saw a storm of activity with many JSRs being filed, expert groups created and specifications defined. At the time of writing, there are 380 JSRs listed on the JCP website with a further 27 maintenance JSRs covering existing specifications.

Another mechanism also exists for accepting and tracking changes to the Java platform: that of JDK Enhancement Proposals (JEPs). Sun finally released the source code of it’s Java Development Kit (JDK) in 2006 under an open source license and started the OpenJDK project to manage this. The Java SE specification defined through the JCP only covers the Java language, virtual machine and class libraries. JEPs cover any modification to the JDK, which may lead to changes being passed into relevant JSRs. As we will see later, these have recently become a topic of some debate.

The Java Specification Participation Agreement

Another important part of the JCP, which I have not mentioned so far, is the Java Specification Participation Agreement (JSPA, pdf). This is significant because it covers the intellectual property (IP) rights associated with JSR specifications. Initially, the JCP did not provide any way for independent implementations of JSRs so there was no ability to produce open source versions.

At JavaOne in 2002, the big announcement was that the Apache Software Foundation (ASF) was joining the Java SE/EE EC. It was also announced that all current and future JSRs led by Sun would be made available under a license that allowed for open source implementations.

Section 5 of the new JSPA covered outbound IP and ensured that the specification lead granted a perpetual, royalty-free, irrevocable license for copyrights and patents covering the specification to anyone who wished to create an independent implementation of the specification. In order to qualify for this, the implementation would have to fully implement the specification, not modify, subset or superset the specification and pass the TCK.

Harmony Strikes the Wrong Chord

For some years the JCP ran smoothly with a wide variety of JSRs submitted, specifications written and both commercial and open source implementations created.

On September 30th, 2004 Java 2 SE 5.0 was launched. This included significant changes to the Java language syntax and also changed the numbering scheme of Java once again. To indicate the level of change to the platform the release number was moved forward to 5.0. Through the JCP, the release contents were specified in JSR 176, which was an “umbrella” JSR. This specification defined contents that also included elements specified by other JSRs, for example generic types from JSR 14, annotations from JSR 175, etc.

Then things got more complicated.

Enter Project Harmony

In May of the following year, a new incubator project was created by the ASF whose goal was “architecting and implementing J2SE 5”. This was known as Project Harmony. For some time prior to this announcement proponents of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) had wanted the source code of Java to be freely available with an open source license. Sun had resisted this call for a variety of reasons; not least of which was the sheer amount of work that due diligence would require to enable them to release the source code under an open source license, but also, as we’ll see, because of how Sun made money from Java.

Since Java’s specifications were freely available from the JCP, in theory, it would be possible to produce a “clean room” implementation that could be distributed free of Sun’s binary licensing terms. The most significant of these was the Field-of-Use (FoU) restriction. The FoU essentially said that Java could be used freely (i.e. without paying Sun a licensing fee) as long as it was used on “General Purpose Desktop Computers and Servers”.

Sun Resists

At this time, the only place that Sun made any revenue directly from Java was licensing Java Card (a tiny subset of Java that ran in only a few kilobytes of RAM) and Java 2 ME, which was used by mobile phone manufacturers. Sun wanted to protect this (not insignificant) revenue stream.

Work on an open source version of Java had started back in 1998 in the form of the GNU Classpath project, but that had only focused on the standard class libraries of Java, not the virtual machine. Project Harmony intended to produce a complete open-source Java runtime environment.

Unfortunately, this is where the problems started. In order for an implementation of JSR 176 to be granted free use of all necessary IP and for it to be called Java that implementation must pass all the tests in the TCK. In August 2006 the ASF approached Sun to gain access to the TCK for JSR 176 (to make things a little more confusing the TCK, in this case, is also referred to as the Java Compatibility Kit (JCK)). Despite the announcements made at JavaOne in 2002, Sun would only provide the TCK/JCK to Apache under certain licensing restrictions. These restrictions meant that any implementation tested would still be constrained by a FoU very similar to Sun’s binary distribution.

Standoff

Apache clearly felt that this was in contravention of the JSPA and wrote an open letter to Sun Microsystems on April 10th, 2007 essentially demanding that Sun honour the terms of the JSPA and provide them with the TCK under an appropriate license. Sun refused to do this.

The impasse was finally resolved after Oracle acquired Sun Microsystems and put the proposed Java SE 7 JSR to a vote of the Java SE/EE EC. This was effectively a vote on whether the licensing terms of the TCK for Java SE would change to allow the ASF access the way they wanted. However, despite the objections of several members of the EC, the vote was passed paving the way for the JCP to return to developing standards as normal.

Tim Peierls and Doug Lea, both individual members of the SE/EE EC resigned in protest. The ASF tried one more time to get Oracle to honour the commitments of the JSPA but eventually resigned from the JCP SE/EE EC in December 2010.

State of Affairs

Since the ASF left the JCP over forty JSRs have been proposed covering all aspects of Java. Does this indicate that all is well now with the JCP? In some ways, yes, but it still has its issues.

Java ME

There are only two JSRs relevant to Java ME from the last few years covering the Connected Limited Device Configuration (CLDC) release 8 and the Java ME embedded profile. Now that mobile phones have moved away from Java ME and many embedded devices are easily powerful enough to run a full Java SE implementation it’s difficult to see where Java ME will go in the future.

From Java SE 8 on, the plan from Oracle was to have Java ME releases in step with Java SE. Right now, it seems unlikely that there will be a Java ME 9 next year.

Java SE

Component JSRs have been submitted for various core platform features. The most significant recently was the Java Platform Module System (Project Jigsaw, JSR 376) to be included in Java SE 9 (JSR 379).

The management of Oracle’s Java Engineering Group recently addressed the JCP EC on the subject of the JSRs for Java SE. The issue they have is that software development has changed a lot in the last twenty years and a more agile approach to the development of the core Java platform is required. JSRs use a structured process for development that does not lend itself well to this methodology.

The JDK Enhancement Proposals (JEPs) were introduced to the OpenJDK project to address this need. JEPs cover smaller pieces of work than a full JSR and can be included or excluded from a JDK release quickly and easily (JDK 9 is already demonstrating this).

Despite the use of JEPs there will continue to be JSRs for Java SE, but they will collect all of the changes when a release is ready to ship, rather than defining these at the start of the development process. This is good because it ensures the IP for Java SE is available under the same terms as before. However, there are some concerns from people wanting to do commercial “clean room” implementations of the JDK, as the only specification reference will be the OpenJDK project until the Java SE JSR is eventually published.

Java EE

Numerous JSRs had been submitted for the various aspects of Java EE such as EJBs, Servlets, Web Services, MVC, etc. all intended to be part of Java EE 8. Recently, though, there was considerable concern in the Java community that most of these JSRs had no activity associated with them and that Oracle was no longer actively developing Java EE. Recent announcements at this year’s JavaOne have promised to put Java EE 8 and 9 back on track so expect to see a lot more progress on these JSRs in the near future.

In the End, It’s All about Community

The JCP certainly faces challenges moving forward. To ensure that standards remain open it is important that membership of the JCP continues to grow. Recent changes to the JCP membership agreement are a clear step in the right direction for this.

Most recently the JCP had elections for the membership of the EC. Since the election was the first to be held under the new version 2.10 rules all seats were up for re-election. The EC is now made up of sixteen ratified, six elected and two associate seats as well as one permanent seat for Oracle America. I am happy to report that the company I work for, Azul Systems, was re-elected for a two-year term and we will continue to help develop the Java platform through this involvement.

Java is different to most other development platforms because of one key factor. Hopefully, the JCP will use this to ensure that Java continues to evolve to meet the ever-changing needs of developers and remains the most popular platform on the planet. The key factor? It’s in the name: Community.

Simon Ritter is the Deputy CTO of Azul Systems. Simon has been in the IT business since 1984 and holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Physics from Brunel University in the U.K. Simon joined Sun Microsystems in 1996 and spent time working in both Java development and consultancy. He has been presenting Java technologies to developers since 1999 focusing on the core Java platform as well as client and embedded applications. Now at Azul Systems he continues to help people understand Java and Azul’s JVM products.

Published in

·Debugging·Development Environment·Patterns & Practices·PHP·Programming·Web·February 26, 2014