Single Sign-On (SSO) Explained

Key Takeaways

- Single Sign-On (SSO) is a process that allows a user to access multiple services after authenticating their identity only once, which eliminates the need for repeatedly confirming identity through passwords or other systems.

- Implementing SSO can be beneficial when developing a product that interacts with other services or when using third-party services, as it ensures that users don’t need to separately log into each service.

- While the SSO process slightly varies across different services, the basic idea remains the same: generating a token and validating it. Strong security measures, such as multi-factor authentication and regular password updates, should be implemented to mitigate risks associated with SSO.

When you’re developing a product for the masses, it is very rare that you would come up with a totally standalone product that does not interact with any other service. When you use a third-party service, user authentication is a relatively difficult task, as different applications have different mechanisms in place to authenticate users. One way to solve this issue is through Single Sign On, or SSO.

Single Sign On (SSO) is a process that permits a user to access multiple services after going through user authentication (i.e. logging in) only once. This involves authentication into all services the user has given permission to, after logging into a primary service. Among other benefits, SSO avoids the monotonous task of confirming identity over and over again through passwords or other authentication systems.

Let’s look at SSO in more detail and we’ll use a very well-known service to demonstrate its uses and benefits.

The Authentication Process

The basic process of SSO is as follows:

- The first step is logging into the main service (Facebook or Google, for instance).

- When you visit a new service, it redirects you to the original (or parent) service to check if you are logged in at that one.

- An OTP (One-time password) token is returned.

- The OTP token is then verified by the new service from the parent’s servers, and only after successful verification is the user granted entry.

Although making the API for SSO is a tedious task, especially in handling security, implementation is a relatively easier task!

A good example of the use of SSO is in Google’s services. You need only be signed in to one primary Google account to access different services like YouTube, Gmail, Google+, Google Analytics, and more.

SSO for Your Own Products

When you are building your own product, you would need to ensure that all its components use the same authentication. This is easy to do when all of your services are confined to your own code base. However, with popular services like Disqus commenting system and Freshdesk for customer relationship management, it is a good idea to use those instead of creating your own from scratch.

But a problem arises with the use of such third party services. As their code is hosted on their respective servers, the user needs to login explicitly on their services even if they are logged into your website. The solution, as mentioned, is the implementation of SSO.

Ideally, you are provided a pair of keys – public and private. You generate a token for a logged in user and send it to the service along with your public key for verification. Upon verification, the user is automatically logged into the service. To understand this better, let’s use a real example.

The Disqus SSO

Disqus is a popular comment hosting service for websites, which provides a load of features like social network integration, moderation tools, analytics, and even the ability to export comments. It started out as a YCombinator startup and has grown into one of the most popular websites in the world!

As the Disqus comment system is embedded into your pages, it is important that the user doesn’t need to login for a second time within Disqus if he or she is already logged in on your website. Disqus has an API with extensive documentation on how to integrate SSO.

You first generate a key called the remote_auth_s3 for a logged in user using your private and public Disqus API keys. You are provided the public and private keys when you register SSO as a free add-on within Disqus.

You pass the user’s information (id, username, and email) to Disqus for authentication as JSON. You generate a message which you need to use while rendering the Disqus system on your page. To understand it better, let us have a look at an example written in Python.

The code examples in a few popular languages like PHP, Ruby, and Python are provided by Disqus on Github.

Generating the Message

Sample Python code (found on GitHub to sign in a user on your website is as follows.

import base64

import hashlib

import hmac

import simplejson

import time

DISQUS_SECRET_KEY = '123456'

DISQUS_PUBLIC_KEY = 'abcdef'

def get_disqus_sso(user):

# create a JSON packet of our data attributes

data = simplejson.dumps({

'id': user['id'],

'username': user['username'],

'email': user['email'],

})

# encode the data to base64

message = base64.b64encode(data)

# generate a timestamp for signing the message

timestamp = int(time.time())

# generate our hmac signature

sig = hmac.HMAC(DISQUS_SECRET_KEY, '%s %s' % (message, timestamp), hashlib.sha1).hexdigest()

# return a script tag to insert the sso message

return """<script type="text/javascript">

var disqus_config = function() {

this.page.remote_auth_s3 = "%(message)s %(sig)s %(timestamp)s";

this.page.api_key = "%(pub_key)s";

}

</script>""" % dict(

message=message,

timestamp=timestamp,

sig=sig,

pub_key=DISQUS_PUBLIC_KEY,

)Initializing Disqus Comments

You then send this generated token, along with your public key to Disqus in a JavaScript request. If the authentication is verified, the generated comment system has the user already logged in. If you have any trouble, you can ask for assistance in the DIsqus Developers Google Group.

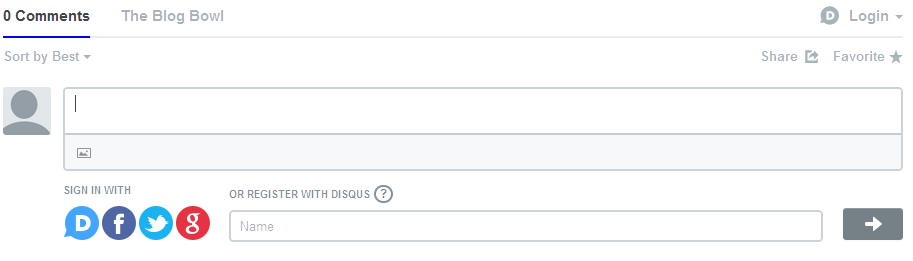

We can see the implementation of SSO on The Blog Bowl, which is a directory of blogs developed in Python/Django. If you are logged into the website, you should be logged in when the Disqus comment system is rendered. In this example, the person object stores the id (which is unique for each person on the site), email, and pen_name. The message is generated as shown below.

sso = get_disqus_sso({

'id': person.id,

'email': person.user.email,

'username': person.pen_name

})On the front end, you just print this variable to execute the script. For a live demo, you can visit this post on the Blog Bowl and check the comments rendered at the bottom. Naturally, you would not be logged in.

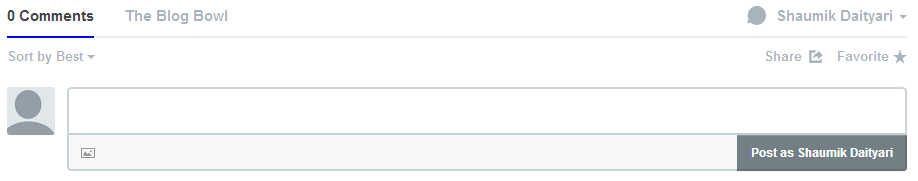

Next, sign into the Blog Bowl, visit the same post again (you need to sign in to view the effect). Notice that you are logged in to the comment system below.

Another interesting feature that the Blog Bowl provides is anonymity while posting content (like this post). Think of a situation when you would want a user to post replies to comments on Disqus as an anonymous user (like on Quora). We took the easy way out and appended a large number to the id. To associate a unique email for the user (so that it doesn’t appear along with other comments by the user), we generate a unique email too. This keeps your anonymous comments together, but does not combine it with your original profile or anonymous comments by other users.

And here is the code:

sso = get_disqus_sso({

'id': 1000000 + person.id,

'email': str(person.id) + '-' + str(post.id) + 'anon@theblogbowl.in',

'username': 'Anonymous'

})Conclusion

Although the SSO processes for different services vary slightly, the basic idea behind them is the same – generate a token and validate it! I hope this post has helped you gain an insight into how applications integrate SSO and maybe this will help you implement SSO yourself.

If you have any corrections, questions, or have your own experiences to share with SSO, feel free to comment.

Frequently Asked Questions about Single Sign-On (SSO)

What is the main purpose of Single Sign-On (SSO)?

The primary purpose of Single Sign-On (SSO) is to simplify the user authentication process by allowing users to access multiple applications or websites with a single set of login credentials. This eliminates the need for remembering multiple usernames and passwords, thereby enhancing user convenience and productivity. SSO also improves security by reducing the chances of password mismanagement and unauthorized access.

How does Single Sign-On (SSO) work?

SSO works by establishing a trusted relationship between multiple applications or websites. When a user logs into one application, the SSO system authenticates the user’s credentials and issues a security token. This token is then used to authenticate the user for other applications within the SSO system, eliminating the need for multiple logins.

What are the benefits of using Single Sign-On (SSO)?

SSO offers several benefits. It simplifies the user experience by reducing the need for multiple logins, thereby saving time and reducing frustration. It also enhances security by minimizing the risk of password-related breaches. Additionally, it can reduce IT costs by decreasing the number of password reset requests.

Are there any risks associated with Single Sign-On (SSO)?

While SSO offers many benefits, it also comes with potential risks. If a user’s SSO credentials are compromised, an attacker could gain access to all applications linked to those credentials. Therefore, it’s crucial to implement strong security measures, such as multi-factor authentication and regular password updates, to mitigate these risks.

What is the difference between Single Sign-On (SSO) and multi-factor authentication (MFA)?

SSO and MFA are both authentication methods, but they serve different purposes. SSO simplifies the login process by allowing users to access multiple applications with a single set of credentials. On the other hand, MFA enhances security by requiring users to provide two or more forms of identification before granting access.

Can Single Sign-On (SSO) be used with mobile applications?

Yes, SSO can be used with mobile applications. Many SSO solutions offer mobile support, allowing users to access multiple apps on their mobile devices with a single set of credentials.

How does Single Sign-On (SSO) improve user experience?

SSO improves user experience by simplifying the login process. Users only need to remember one set of credentials, reducing the frustration of forgotten passwords. It also saves time, as users don’t need to repeatedly enter their credentials when accessing different applications.

What industries can benefit from Single Sign-On (SSO)?

Virtually any industry can benefit from SSO. Industries that rely heavily on multiple applications, such as healthcare, education, finance, and technology, can particularly benefit from the convenience and security that SSO provides.

How does Single Sign-On (SSO) enhance security?

SSO enhances security by reducing the number of passwords that users need to remember and manage. This decreases the likelihood of weak or reused passwords, which are common targets for cyberattacks. Additionally, many SSO solutions incorporate additional security measures, such as multi-factor authentication and encryption, to further protect user data.

Can Single Sign-On (SSO) be integrated with existing systems?

Yes, most SSO solutions can be integrated with existing systems. However, the integration process may vary depending on the specific SSO solution and the systems in place. It’s important to work with an experienced IT team or SSO provider to ensure a smooth and secure integration.

Shaumik is a data analyst by day, and a comic book enthusiast by night (or maybe, he's Batman?) Shaumik has been writing tutorials and creating screencasts for over five years. When not working, he's busy automating mundane daily tasks through meticulously written scripts!

Published in

·automation·Cloud·Debugging & Deployment·Meta·Open Source·PHP·Programming·Web·July 17, 2014