- 1. What Social Problem Does Your App Aim to Address?

- 2. Is Your App Stand Alone or Part of Something Bigger?

- 3. Is the Technology Credible?

- 4. What Are the Consequences of Using the App?

- 5. Have You Anticipated Unintended Consequences?

- 6. Don’t Forget to Consider Predecessors That Have Failed

- 7. What’s Missing?

- Conclusion

When I began working on this article, I intended to focus on crime reporting apps. But I found it impossible to remove crime from the society it’s part of. I decided to look at a broader scope which covered police surveillance, neighborhood watch, human rights abuses, child sex trafficking and how mobile phone apps can record and report these crimes.

Mother Jones did a report of 13 killings by police captured on camera, that included six fatal shootings captured by bystanders using mobile phones. As the article demonstrates, these apps can be more contentious than first appears. Here’s some thoughts on tips to consider when developing a social based app.

1. What Social Problem Does Your App Aim to Address?

It’s easier to create a problem solving app if you focus on a specific aim and audience, rather than try to be all things to all people.

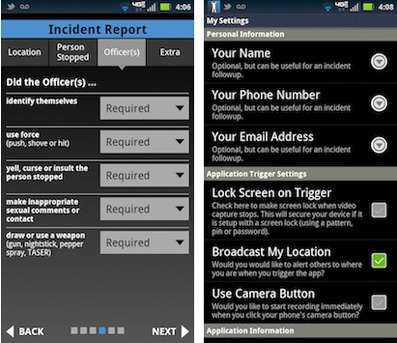

For example the Stop and Frisk Watch App was a response to unlawful ‘Stop and Frisk’ searches, where police stop and question a pedestrian, then frisk them for weapons and other contraband. Due to findings that nearly nine out of 10 stopped-and-frisked New Yorkers have been innocent (and black and latino men are the most likely targets), the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) created an app that enables bystanders to document stop-and-frisk encounters and alert community members when a street stop is in progress.

An incident is recorded by pushing a trigger button on the phone. Shaking the phone stops the filming. When filming stops, the user receives a brief survey allowing them to provide details about the incident. The video and survey are sent to the NYCLU, who use the evidence in their advocacy campaigns. The app alerts users when people in their vicinity are stopped by the police, which is useful for community groups who monitor police activity.

There are a plethora of Neighborhood based apps focused on creating communication between residents of local neighborhoods. these range from issues like events, lost items and garage sales to local crime spotting. An example is Next Door, which connects people within their geographical neighborhoods around local issues.

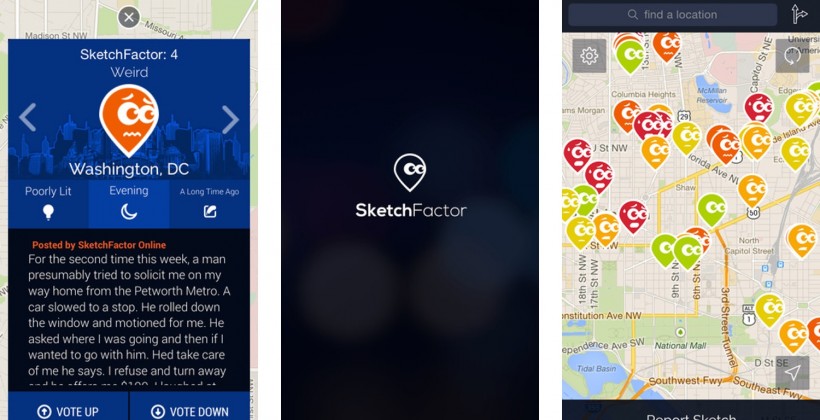

Sketch factor is a community driven navigation app that shows the relative “sketchiness” (security) of an area. The app uses crowd-sourced data from users to pinpoint “sketchy” areas and provides safe walking directions.

Apps like the UK’s Self evident aim to provide a conduit between civilians and police when a crime has occurred. Working in conjunction with local police forces across the UK, Self evident can record a statement, validate the evidence for an insurance or compensation claim and file a crime report with the police from the user’s smartphone.

The Freedom app is a human trafficking app that aims to identify and rescue people from international sex trafficking. It encourages people to report suspected incidences of trafficking and any information they may have.

The eyeWitness app is part of work by international humans rights activists bringing justice to those responsible for war crimes, torture or genocide in conflicts such as those in Syria, Ukraine and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The app provides a means to record images and videos with the addition of a time-stamp and GPS-fixed location and further provides a safe place to store the material. The eyeWitness team then becomes an ongoing advocate for the footage, analyzing the information and working with the appropriate legal authorities to promote accountability for those who commit the worst international crimes.

2. Is Your App Stand Alone or Part of Something Bigger?

Any app focused on issues such as community, crime detection and reporting cannot be considered credible unless it originates from key agencies or partner with relevant organizations to provide resources and information for app users. Think about it in your own life. If you saw a crime committed by police, would you know where and how to report it? Unlikely for most people, which makes the work of organizations like the NYCLU all the more pertinent. Their app includes a “Know Your Rights” section that instructs people about their rights when confronted by police and their right to film police activity in public. Likewise, Self evidence partners directly with local police authorities and the makers of the Freedom app, Orphan secure, works in cooperation with trusted law enforcement agencies and other NGOs.

3. Is the Technology Credible?

Will your app work offline or when a central server is overloaded? If your app aims to record crimes as they occur, is the footage/dialogue gained from your app admissible in court?

If it does not contain the date, time, or geographic coordinates it may be difficult, if not impossible to verify that the footage is original and has not been altered. Verification is challenging if the individual who captured the footage wishes to remain anonymous. In case of counter claims that evidence has been falsified or digitally altered, eyeWitness for example, incorporates a counter that records the number of pixels to demonstrate that images have not been digitally manipulated.

4. What Are the Consequences of Using the App?

If an app is used to record witness statements for at the scene of a crime, who is asking questions to the witness? It may be tempting to interview bystanders like the news channels do, but if witness statements later change, it may compromise any legal proceedings. How much legal information will you provide with your app?

Further, what happens if a person is caught recording a crime? Kevin Moore, the man who filmed the now infamous Freddie Gray arrest, just before police apparently killed the Baltimore resident in the back of a police van, was harassed continuously after he filmed the police. Following that harassment, he was arrested and charged with crimes that included “terrorism”, “inciting a riot” and “evading police”. These crimes were dropped a day later.

NYCLU note that their app should be used with caution but it’s odd that the app has no means of simultaneously uploading data while recording in case police grab the phone and erase the video. By comparison, eyeWitness film can be deleted once sent and there is a “panic button” that allows the user to erase all recorded information as well as the app itself.

5. Have You Anticipated Unintended Consequences?

A number of apps have been accused of inciting racism and stereotyping. For example, a neighbor posted in detail on Nextdoor about the race and wardrobes of two “sketchy” men “lingering” outside her house. They turned out to be friends of another neighbor on Nextdoor who were invited to her home for a party.

Bizarrely, residents organized a “whites-only” meeting to address the issue of how to properly report and describe suspicious people. Nextdoor can become a forum for paranoid racism, the equivalent of the nosy Neighborhood Watch appointee in a gated community.

Sketch Factor has been subject to similar accusations of racism, particularly for labelling black neighborhoods as ‘sketchy’ and has been called an app for whites to avoid colored neighborhoodsby some critics. As well as poor moderation of comments and reviews, Sketch Factor fairs poorly in offering current information as reports of areas stay on the app for 1 year.

Not all unintended consequences are bad. Developer Pham used the Next Door app in response to a hate crime six blocks from his home whilst he was away. He was able to organize a weekend candlelight vigil attended by 500 people and raised over $27,000 from 268 individual donors as a reward to catch the person who committed the crime.

6. Don’t Forget to Consider Predecessors That Have Failed

Crowd Solve addresses the issue of people in prison due to wrongful conviction. With a premise familiar to fans of Serial and the work of Innocence Project, the contention was that the wisdom of the collective crowd would work together via the internet (and visualization tools, access to raw case data and files, and “powerful evidence indexing”) to solve crimes where the wrong person had been charged and the real criminal was free.

Crowdsolve failed on Indiegogo, perhaps due to the bizarre accompanying video which suggested people could solve crime in the locker room after a workout or whilst pretending to work at their day job. There are bigger issues of the impact of amateur sleuths opening closed crimes and the propensity for mob mentality to get it wrong. I’m thinking of when Reddit contributors pledged to identify the Boston Marathon Bomber and as a consequence inaccurately identified deceased student Sunil Tripathi as the bomber. Even the Reddit General Manager admits it was a disaster all round.

7. What’s Missing?

I have been unable to find any apps that address the issue of cyber crime or white collar/corporate crime. Whether created for recording, reporting and education provision, they may be a useful additions to this app genre.

Conclusion

The article provides a brief analysis of a range of apps which aim to respond to social problems and particular crimes. Neighborhood based apps have taken the place of the neighborhood social meeting point. Crime apps are used extensively by police and civilians around the world to prevent and respond to different types of activity.

They have opportunity to provide a concise, accessible and immediate means to respond to criminal activity. But they also can prove inadequate, offensive or even put individuals at risk. What are your experiences with these kinds of apps? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Cate Lawrence

Cate LawrenceCate Lawrence is a Berlin based writer and blogger who spends her spare time cooking and teaching her cat to chase a red dot.