Today we are joined by none other than Brendan Eich, creator of the JavaScript programming language, co-founder of the Mozilla project and most recently CEO of Brave Software—a start-up that aims to transform the online ad ecosystem with faster and safer browsing.

Brendan is joining us to talk about the Brave browser—a new browser which automatically blocks ads and trackers and which will soon incorporate a micropayments system to offer users a choice between viewing selected ads, paying websites not to display them, or even going “ad free for free”.

Elio: Brendan, thank you for sparing the time to talk to us. I guess these past few months have been pretty busy for you?

Brendan: Very!

Elio: Could you start by telling us who Brave is tailored to? Is it aimed at your average user, or those who are more technically savvy?

Brendan: Brave is for all people who care about their privacy and browsing speed on the Web, which are closely related concerns due to the rise of intrusive, inefficient, and even dangerous third party advertising technology.

Elio: And how is using Brave different to the current status quo (i.e. users installing ad-blockers and privacy extensions)? For example, will it protect people from malware served via ads?

Brendan: Brave blocks ads and their tracking cookies and “pixels” by default, without taking fees to let some through as top ad-blocking browser extensions do. We restore secure https: links where possible, to use HTTPS everywhere. We will also defend against various kinds of fingerprinting.

On our roadmap: a private/anonymous ad system where the advertisers do not have the means to track our users, but will have authentic measures of ad performance that are truly anonymous. Our users’ data stays only on their own devices; even Brave servers never see it. All the ad matching logic runs on-device too. To prove valid ad impressions we use a new protocol based on zero-knowledge proofs.

From this business, we give our users the same cut of the gross ad revenue as we take.

Elio: The business model is obviously controversial. One concern I heard voiced recently went as follows: “If I don’t like Brave, but I own a site, I have no choice but to deal with them. They take the ad network I chose to deal with, replace it with their own, and make me go to them to get my money after they take their cut.” Can you answer that?

Brendan: Sure.

First, we have many ways of working with publishers. Our ad replacement system won’t replace all ads, instead focusing on the standardized “programmatic” ads that are most intrusive and even dangerous today. These ads are matched and placed by layers of intermediaries in a complex ecosystem. Many publishers run such ads, but no publishers can control exactly which ads win the “real-time bid” process by which programmatic ads are placed.

This is why malvertisement (ransomware) has been able to get onto the New York Times and the BCC websites. Almost all publishers use third party ads, but none wants to take the blame when attackers exploit the over-delegated, non-contractual system of middle-players in ad-tech.

Even setting aside malware, programmatic ads bother many users with inappropriate, intrusive, and even abusive practices. People do not like being retargeted across sites and devices, especially if the ad isn’t working — or has already worked and the user bought what was advertised. Brave is a browser, so with high privacy, only on your device, it can do a better job avoiding such pitfalls.

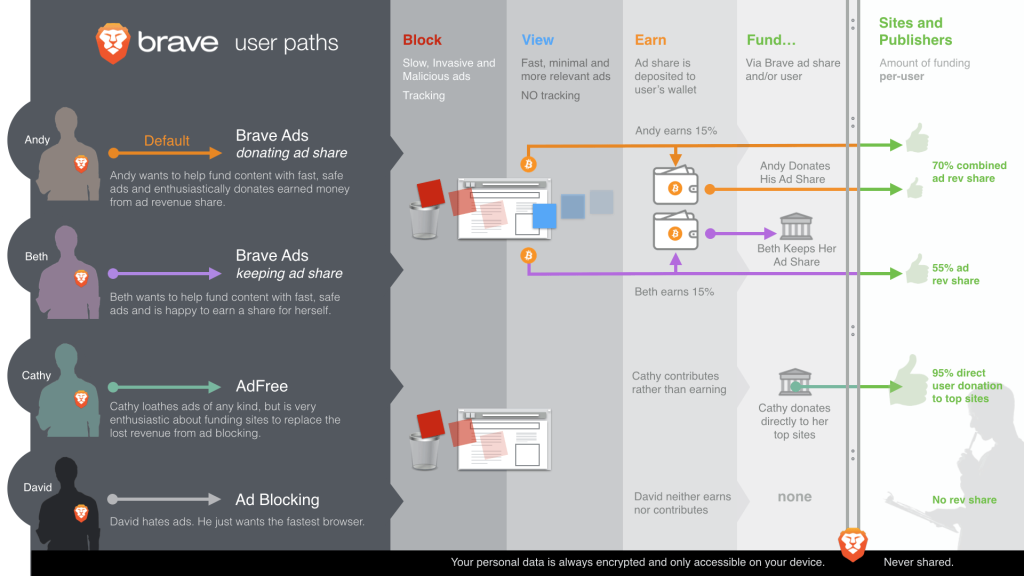

Finally, because of all the middle-players, the revenue left in the pie for the publishers is small and shrinking. The IAB 2014 Programmatic Ads study found 45% left for publishers, and I’ve heard of much lower shares. Brave has a transparent revenue share that gives 55% directly to publishers for the kind of ads we replace, which we believe will cleanly beat like for like ads.

On top of this, we will give 15% to our users, and by default trickle that back to their favorite sites. So the aggregate share of revenue to websites is 70% with Brave, same as with Facebook Instant Articles and Apple’s App Store.

A second way we will work with publishers addresses the concerns from some of the big ones, that their best inventory is direct-sold, or sold via private marketplaces, and they get better net revenue than from programmatic ads. We do not propose to replace these direct or even “native” ads; we agree publishers often place the best image for the slot in this kind of advertising.

The problem these publishers face from all ad-blockers (all else equal — especially discounting the top ad-blockers’ practice of taking fees prospectively to let ads and trackers through from the fee-paying network) is that direct/native ads are also full of tracking cookies and pixels (so-called from when 1×1 images were used; today, often pure JS scripts). Ad blockers worth their salt, and definitely Brave, block these trackers and signals for getting paid based on ad performance.

But with Brave, we have private on-device ad-matching and anonymous zero-knowledge-based impression and click confirmation. So we will work with top publishers to let their best ads place, but without any third party tracking systems that damage both privacy and speed.

A final way we hope to work with publishers: since we have a permissionless bitcoin-under-the-hood payments system built into Brave, which we use to share revenue with both users and publishers, we can add micropaywall features for each publisher. If a publisher needs several price tiers for micropaying readers, we will accommodate. We hope to innovate in the space between micropayments and “micro-kickstarters” so each article finds enough readers to pay its cost of production — and great articles win lots of reward on top of its kickstarter-like cost goal.

Elio: If I’m understanding things correctly, for Brave’s block-and-replace model to work, Brave will have to work directly with all of the big advertising networks. But at the same time, Brave will be blocking ads from those same advertising networks. Will those advertisers have to pay twice: once for the spot on the website—which gets automatically stripped out—and then again so that Brave will display their ad as well?

Brendan: Let me answer that in two parts.

If I’m understanding things correctly, for Brave’s block-and-replace model to work, Brave will have to work directly with all of the big advertising networks.

No. Ad networks aggregate ads and so use cookies and tracking pixels, as detailed above. Instead, we go to the source of ads: brands and agencies who work for them.

But at the same time, Brave will be blocking ads from those same advertising networks. Will those advertisers have to pay twice: once for the spot on the website—which gets automatically stripped out—and then again so that Brave will display their ad as well?

No, and this shows a common misunderstanding of how ads pay. Advertisers do not pay for ad spaces in advance. They pay based on economic performance, whether measured by impression counts (typically patched into thousands, Latin Millenia, hence CPM for Cost Per Millennium) or further attributable actions (clicking to download a new app, e.g.).

Further, ads on the web are not like ink-on-paper newspaper ads. The browser typically fetches scripts which, even in the direct/native case but always in the programmatic case, do the work of fetching the right ads. Some ads are almost pure images on the publisher’s page, but these are one-size-fits-all “sponsorship” or “brand” ads. Even these ads, as noted above, have tracking at least for confirming impressions and counting other beans.

Ad blockers block ads and therefore publishers do not get paid for any space they’ve given up, for those users running the blockers.

Only Brave has a model for recovering lost revenue, even beating the low rev-share of the ads we aim to replace.

Elio: Instead of tracking you around the net, Brave will use your local browsing history to target ads. What (if anything) will you do with info you collect? Where will it be stored?

Brendan: We don’t collect (which my dictionary says means “to get (things) from different places and bring them together”) onto our servers at all. Instead your data stays stored on your device, and that is where Brave code studies it to give you the value you’re due from such analysis. This is different from today’s cloud-based services which track, aggregate, and study en-masse without sharing revenue with you.

As with all browsers, we provide means to clear history, and we’ll also provide affordances for clearing the results of the local studies. These can be of value to users purely for self-profiling, but as noted above, we hope to provide a better ad model, because much of the Web depends on ads and users seem unwilling or unable to pay for most content.

Elio: Sites can now detect users with adblockers and block them based on that. Will sites be able to detect people running Brave and block them in the same way?

Brendan: Sure, and some already do. But we work around such blocker-blockers, e.g. at forbes.com, and we relish a little arms-racing on behalf of the user. The arms-race so far has gone on in the cloud, to the user’s detriment.

We also note a claim out of Europe that sites that block ad-blockers violate the EC’s privacy regulations.

We’re following this story with interest.

Elio: Can you give us the technical lowdown on Brave? For example which rendering engine is it built on? How do its dev tools compare with those of other browsers and if there is anything else that makes it attractive for devs?

Brendan: On Mac OS X and Windows we use the same chromium engine that Chrome uses, and we are automating as we go to track closely to the stable release.

We have the chromium devtools built-in and we’re working on improving their user interface.

In general we aim to neutralize Chrome by using its open source code, and differentiate where Chrome cannot go: blocking ads and trackers (including Google Doubleclick — but not first-party Google search ads, note well).

On mobile we use the OS webview: chromium-based on Android, and UIWebView currently on iOS (it has the rich network request-level blocking APIs we need).

Elio: Are there any exciting features coming in new releases? For example when will we get plugins?

Brendan: Plugins are dying thanks to their being banned by Steve Jobs on iOS and then dropped from Android. Indeed plugins such as Flash are the exploitable native code targeted by malvertisement kits such as the Angler Exploit Kit. So we are taking a hard line on Flash and other plugins: we will allow them only for sites on a controlled list, and “time out” their approval on any such list, whether we curate it or let users opt in one by one.

We’ll have more to say about plugins over time, unless they go away sooner. They are zombies from the ’90s, the walking dead.

Elio: Ah no, sorry, I meant extensions. You know, things you can install from the Google web store (for example), that enhance the functionality of your browser. Will they be coming to Brave any time soon?

Brendan: Actually, Brave has been supporting extensions since early April, with our 0.9 developer release. We started with password manager support, and now have bundled 1Password. Support for DashLane, MasterPassword, and LastPass is right around the corner. We also have plans to support more extensions over the next few months, as extension authors validate our build signature so their standard distribution can run in Brave.

Elio: I read recently that a number of major U.S. newspaper publishers have sent you a cease-and-desist letter regarding Brave, calling the browser “blatantly illegal”. Have there been any developments since this story was first reported?

Brendan: Not really, and the letter itself said neither “cease” nor “desist”, since we aren’t doing anything discussed above in the way of ad replacement yet.

Elio: What has Brave’s uptake been like? You stated you needed 7 million users to “hit critical mass”—are you near that?

Brendan: Not yet, but we’re growing nicely as we work toward 1.0.

Elio: You are the father of JavaScript, so I have to ask: How much has JavaScript contributed to creating the problem that Brave is trying to solve?

Brendan: The problem predates JS: in 1993, Marc Andreessen announced the HTML img tag, which can load cross-site. In 1994, Lou Montulli created the cookie at Netscape, for first-party login credential caching (so you don’t have to log into a server every time you visit it). The two innovations combined to create third-party tracking: by embedding an image, even a 1×1 pixel, in two sites, the third party hosting the image could store an identifier in a cookie associated with its domain, and through the URLs used to embed the image, see the two sites’ addresses too.

JS came in 1995 and I didn’t get cross-site script loading going until Netscape 3 in 1996. This added fuel to the fire but it was neither first nor did it replace images and cookies.

Elio: And staying with JavaScript (if I may): What are some of the things you see JavaScript being used for, which you never intended it to be used for. Is there anything which has really surprised you?

Brendan: Cross-compiling Unity and Epic (Unreal Engine) and other C++ games to the Web.

Elio: What are your predictions for the future of JavaScript—could you name one or two technologies that will (in your opinion) have the biggest impact in the coming year.

Brendan: WebAssembly. ES6 and what lies beyond for pure JS.

Elio: Thank you for your time, Brendan. I wish you the best of luck with Brave’s future development.

And for those of you interested in finding out more, please visit Brave’s Response to the NAA: A Better Deal for Publishers for further background on the business model and how Brave shares revenue. You can download Brave here.

What are your thoughts on Brave? Let us know in the comments below.

Frequently Asked Questions about Brendan Eich and Brave

What is Brendan Eich’s net worth?

Brendan Eich, the CEO of Brave, has an estimated net worth of $50 million. This wealth has been accumulated through his various roles in the tech industry, including his time as the creator of JavaScript and as a co-founder of Mozilla. His current role as the CEO of Brave, a privacy-focused web browser, also contributes to his net worth.

What is Brendan Eich’s contribution to the crypto world?

Brendan Eich is a significant figure in the crypto world due to his role in the creation of Basic Attention Token (BAT), a blockchain-based system for tracking media consumers’ time and attention on websites. BAT is integrated within the Brave browser, allowing users to earn tokens by viewing opt-in ads.

What is the Brave browser and how does it work?

Brave is a free and open-source web browser that focuses on providing privacy and blocking intrusive ads and trackers. It is built on the Chromium web browser and its Blink engine. Brave also integrates with the Basic Attention Token (BAT) system, allowing users to earn and donate tokens for viewing opt-in ads.

What is Brendan Eich’s educational background?

Brendan Eich holds a bachelor’s degree in Mathematics and Computer Science from Santa Clara University and a master’s degree in Computer Science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

What is Brendan Eich’s role in the creation of JavaScript?

Brendan Eich is the creator of JavaScript, one of the most widely used programming languages today. He developed JavaScript while working at Netscape Communications in just ten days in 1995.

What led to Brendan Eich’s departure from Mozilla?

Brendan Eich stepped down from his role as CEO of Mozilla in 2014 following controversy over his past donation to a campaign supporting Proposition 8, a California ballot proposition against same-sex marriage.

How does Brendan Eich’s Brave browser protect user privacy?

Brave browser is designed to automatically block third-party ads, trackers, and autoplay videos, thereby protecting users’ privacy. It also offers features like HTTPS Everywhere for secure connections and private browsing with Tor for enhanced privacy.

How does the Basic Attention Token (BAT) system work?

The Basic Attention Token (BAT) system is a blockchain-based digital advertising platform that measures users’ attention to ads. Users earn BAT tokens for viewing opt-in ads, which they can then donate to content creators or use to access premium content.

What is Brendan Eich’s vision for the future of the web?

Brendan Eich envisions a future where the web is free from intrusive ads and trackers, and where users have control over their own data. He believes that the Basic Attention Token (BAT) system and the Brave browser are steps towards this future.

What are some of Brendan Eich’s notable achievements?

Apart from creating JavaScript and co-founding Mozilla, Brendan Eich is also known for his role in the development of the Netscape Navigator web browser. His current project, the Brave browser, has also gained significant recognition for its focus on privacy and ad-blocking.

Elio Qoshi

Elio QoshiElio is a open source designer and founder of Ura Design. He coordinates community initiatives at SitePoint as well. Further, as a board member at Open Labs Hackerspace, he promotes free software and open source locally and regionally. Elio founded the Open Design team at Mozilla and is a Creative Lead at Glucosio and Visual Designer at The Tor Project. He co-organizes OSCAL and gives talks as a Mozilla Tech Speaker at various conferences. When he doesn’t write for SitePoint, he scribbles his musings on his personal blog.