Ever since we started creating graphical user interfaces, we’ve been trying to make them friendlier and more usable. Sometimes those two goals coincide; sometimes they don’t.

Striking a balance

Designers know that using one font for all H3 headings, for example, indicates to users that the information under each heading sits at the same level of “depth”, or has equal “weight” to the others in the overall scheme of a piece of content. So the interface designer has given equal weight to the two user options shown below: they take the same font, and each has an image.Look who’s talking

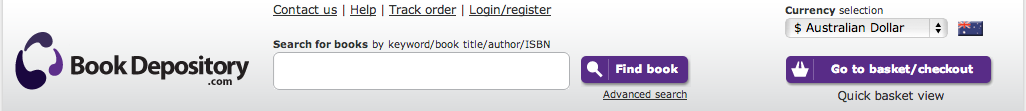

So far we’ve looked at small, straightforward interface examples. If you’re the kind of designer who thinks your CMS interface, for example, doesn’t need to talk to users in their own language, you might be thinking none of this applies to you. So let’s look at a retail example: the Book Depository. Remember how I said a lack of application of grammatical techniques like articles can add up? Here’s a great case in point. Applying the couple of principles we’ve already discussed, let’s see how we can make these labels less like something a robot would say, and more like something an approachable brand would say:

Remember how I said a lack of application of grammatical techniques like articles can add up? Here’s a great case in point. Applying the couple of principles we’ve already discussed, let’s see how we can make these labels less like something a robot would say, and more like something an approachable brand would say:

Login/register

Login or register OR Login | Register

Search for books by keyword/book title/author/ISBN

Search on a book title, keyword, author or ISBN

Find book

Find books OR Search for books

Currency selection

Choose a currency

Go to basket/checkout

View your basket OR Checkout

Clearer interfaces, clearer communication

It’s true: sometimes grammar is the interface designer’s nerdy but smart friend! Don’t waste time and energy creating a gorgeous, friendly brand, but let computer-speak creep into your interfaces. With the kind of grammar we already know, we can carry those brand values through to the smallest snippets of interface text — sometimes making them more compact, but in every case making them more communicative.Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Bad Web Grammar and User Experience (UX)

Why is good grammar important in UX design?

Good grammar is crucial in UX design because it ensures clear communication. Poor grammar can lead to misunderstandings, confusion, and frustration for the user, which can negatively impact their experience on your website. It can also make your site appear unprofessional, which can harm your credibility and trustworthiness. Therefore, it’s essential to ensure that your website’s content is grammatically correct and easy to understand.

What are some common grammar mistakes in UX design?

Some common grammar mistakes in UX design include incorrect use of punctuation, misspelled words, incorrect verb tenses, and misuse of homophones (words that sound the same but have different meanings). These mistakes can make your content difficult to understand and can negatively impact the user’s experience.

How can I avoid grammar mistakes in UX design?

To avoid grammar mistakes in UX design, it’s important to proofread your content carefully before publishing it. You can also use grammar checking tools, such as Grammarly, to help identify and correct any errors. Additionally, it can be helpful to have someone else review your content, as they may spot mistakes that you’ve overlooked.

Can bad grammar affect my website’s SEO?

Yes, bad grammar can negatively impact your website’s SEO. Search engines like Google prioritize high-quality content, and grammar mistakes can make your content appear low-quality. This can result in lower search engine rankings, which can reduce your website’s visibility and traffic.

What is the impact of bad grammar on user engagement?

Bad grammar can significantly impact user engagement. If users struggle to understand your content due to grammar mistakes, they’re likely to leave your site and not return. This can result in lower engagement rates, which can negatively impact your website’s performance.

How can I improve the grammar on my website?

To improve the grammar on your website, consider hiring a professional editor or proofreader. They can review your content and correct any grammar mistakes, ensuring that your content is clear and easy to understand. You can also use online grammar checking tools to help identify and correct errors.

What are some examples of bad UX due to poor grammar?

Examples of bad UX due to poor grammar can include confusing navigation menus, unclear instructions, and misleading information. These issues can make it difficult for users to use your website effectively, leading to frustration and a poor user experience.

How does good grammar contribute to good UX?

Good grammar contributes to good UX by ensuring clear and effective communication. It helps users understand your content, navigate your site, and complete desired actions. This can lead to higher user satisfaction, engagement, and conversion rates.

Can good grammar improve my website’s conversion rates?

Yes, good grammar can improve your website’s conversion rates. Clear and error-free content can enhance your site’s credibility and trustworthiness, which can encourage users to take desired actions, such as making a purchase or signing up for a newsletter.

What resources can I use to improve my grammar skills?

There are many resources available to help improve your grammar skills. Online courses, grammar books, and grammar checking tools can all be useful. Additionally, practicing writing regularly and getting feedback from others can also help improve your grammar skills.

Georgina has more than fifteen years' experience writing and editing for web, print and voice. With a background in marketing and a passion for words, the time Georgina spent with companies like Sausage Software and sitepoint.com cemented her lasting interest in the media, persuasion, and communications culture.