Mobile Accessibility Fails: Do we need a WCAG3?

Key Takeaways

- The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) have not kept pace with the evolution of technology, particularly with regard to mobile accessibility.

- There is a need for implementation criteria and specific techniques for mobile accessibility, which are currently lacking in WCAG2.

- Common mobile accessibility issues include hover inaccessibility, keyboard focus traps, and mobile hover traps, which are not adequately addressed in the current guidelines.

- To ensure accessibility for all users, there is a need for further development of specific mobile techniques, potentially leading to a WCAG3.

Back in 2005 when I attended my first (and only) face-to-face WCAG Working Group event in Seattle we couldn’t even comprehend where technology would be today; with the array of smartphones, tablets, laptops and smartwatches to come.

Nevertheless, we were very focused on making the second version of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines ‘technology neutral’; so that it would still be applicable to any of the myriad of future technologies available now.

In some cases, we were successful, but when it comes to mobile accessibility, unfortunately, we were not.

The W3C has released a discussion paper on Mobile and accessibility and how it relates to WCAG2. It is a good read, but it doesn’t provide any implementation criteria. It does list WCAG2 Techniques that apply to mobile, but there is no information on how they apply to mobile, and there aren’t any additional techniques that are specific only to mobile.

At AccessibilityOz, we started testing mobile-only sites early last year. Initially, we used the BBC Mobile Accessibility Guidelines and merged them with WCAG2 to conduct our testing.

However, we quickly realised that this wasn’t enough; we found a number of things that were not covered in WCAG2 or the BBC Mobile Accessibility Guidelines and considered many of them quite serious accessibility issues.

This resulted in us developing our own unique AccessibilityOz Mobile Testing Methodology which we have since used in our testing of many mobile-only and responsive websites.

There are a number of ways that viewing a website (whether it is optimized for mobile or not) on a mobile device can be problematic. Here I am going to focus on hover inaccessibility.

Firstly we know that on a mobile device there is no continual access to a keyboard (unless someone is using it as an add-on to the device – or using a Blackberry Classic). WCAG2 requires that all content be accessible to the keyboard interface, but it does not require that all content be accessible to a mouse or to a touchscreen user. The definition of a ‘keyboard interface’ in WCAG2 makes this very clear:

WCAG definition of keyboard interface – interface used by software to obtain keystroke input (link1)

Note 1: A keyboard interface allows users to provide keystroke input to programs even if the native technology does not contain a keyboard.

Example: A touchscreen PDA has a keyboard interface built into its operating system as well as a connector for external keyboards. Applications on the PDA can use the interface to obtain keyboard input either from an external keyboard or from other applications that provide simulated keyboard output, such as handwriting interpreters or speech-to-text applications with “keyboard emulation” functionality.

Note 2: Operation of the application (or parts of the application) through a keyboard-operated mouse emulator, such as MouseKeys2, does not qualify as operation through a keyboard interface because operation of the program is through its pointing device interface, not through its keyboard interface.

That means that a UI component that is accessible to an external keyboard on a mobile device can actually comply with WCAG2; even if it is not accessible via a mouse or via touch. WCAG2 was written this way as back in the 2000s it was incomprehensible that a website would be created that was not mouse-accessible. Keyboard accessibility had to be included in WCAG2 though as it was (and still is) quite common to find keyboard-inaccessible websites. And of course, we didn’t even think of touch accessibility.

However, instead of a pointing device, users only have the ability to activate components on the mobile. There is no equivalent ability to ‘hover’ over a component, as you can with the mouse or ‘focus’ on a component, as you can with the keyboard. This can cause a range of functionality problems.

Activating Menu Items

Dropdown or flyout menus are very popular at the moment. In many cases, you hover over the top-most menu item to reveal its sub-menu items.

If that main menu item is actually a link to another page, then this hover feature can’t be replicated on a mobile device. Tapping on the main menu item will just take users to that page; there is no way to replicate the mouse hover effect on a mobile (well some mobile devices have the ability to replicate the hover effect but it certainly isn’t a well-known technique). This is one reason that in order to activate the flyout menus on the AccessibilityOz website, you need to actually click on the top-most menu item.

For sites that make this top menu item a link, mobile users have only one option: to activate that top menu item. This means they cannot access the dropdown or flyout menu, as touching the top menu item will activate the link – taking the user to that particular page.

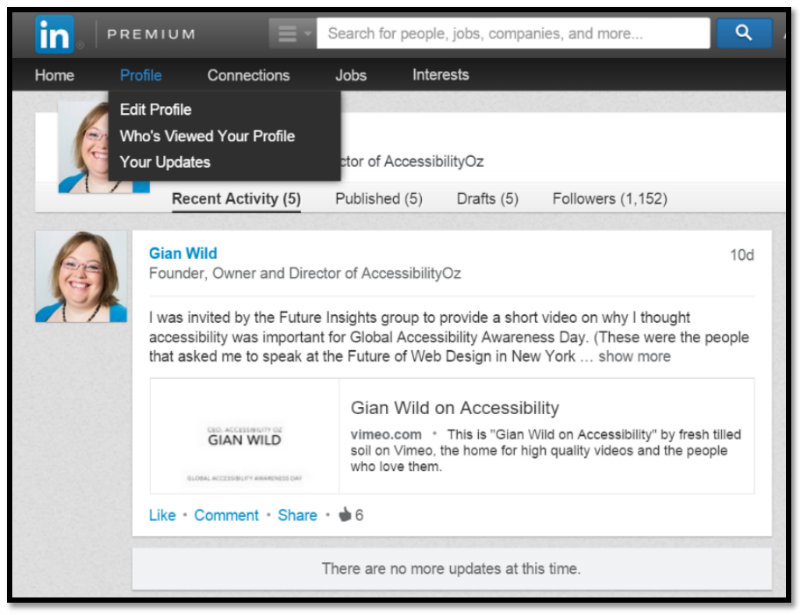

We can see this scenario on LinkedIn.

Figure 1: Drop-down appears only on mouse hover or keyboard focus.

If you access this page on a mobile device, it’s impossible to activate the dropdown. Touching the ‘Profile’ top menu item takes you to the Profile page.

Keyboard Focus Traps

Most people are aware of the term “keyboard trap”. It is when a keyboard user gets trapped within a particular component, such as a video player. There is often no way to exit from the keyboard trap other than closing the browser window. We have also come across what we term a “reverse keyboard trap”; where the keyboard activates a component which cannot be closed.

Although the user can continue tabbing through the page, the component overlaps other content which can make the site difficult, or almost impossible, to use. We have also come across what we term a “reverse keyboard trap”; where the keyboard activates a component which cannot be closed. Although the user can continue tabbing through the page, the component overlaps other content which can make the site difficult, or almost impossible, to use.

Of course, this is a serious accessibility issue – not to mention a huge UX concern – and is one of the four non-interference success criteria in WCAG2.

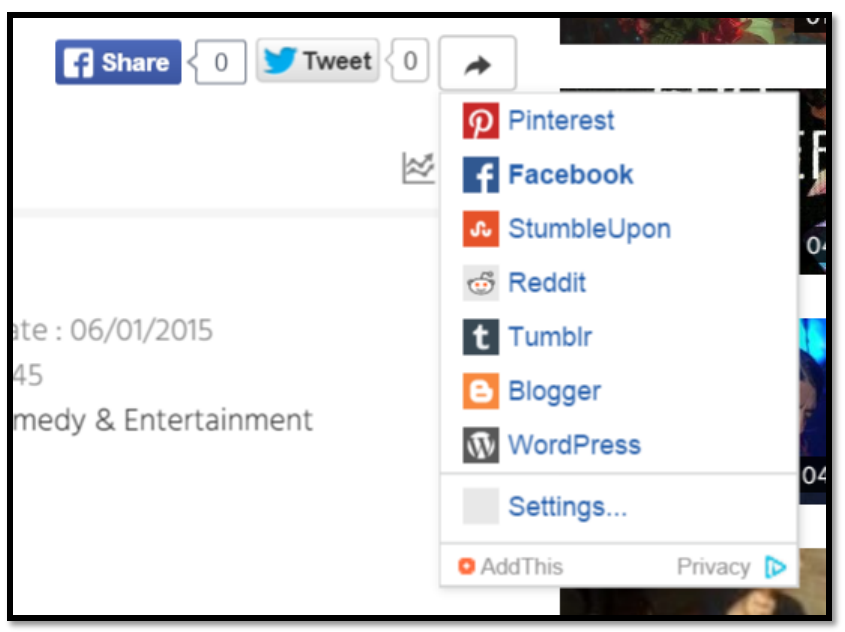

A non-interference success criterion is a requirement that an entire site needs to meet in order to claim accessibility even for only a section of that site. We see the ‘AddThis’ plugin as a keyboard trap on a lot of sites – for example, www.theage.com.au.

We have also come across a different type of keyboard issue, which we call a “Keyboard Focus Trap”. When focussing on a component with the mouse, a popup or ‘tooltip’ appears. When moving the mouse away, this popup disappears. When activated on keyboard focus, this popup appears, but it does not disappear when keyboard focus is removed. We can see this in action on DailyMotion with the AddThis plugin.

Figure 2: Popout appears on keyboard focus but does not disappear when keyboard focus is removed.

Thankfully, on the DailyMotion mobile site, this Addthis functionality is withdrawn. However, we often see a similar error in mobile devices.

Mobile Hover Traps

Some sites provide additional functionality when the mouse hovers over an item, or when it has keyboard focus. The most obvious of these is the TITLE attribute that can be added to links, images and fields. The contents of the TITLE attribute appears on a tooltip on mouse hover and disappears when the mouse moves away.

<a href="http://example.com" title="Visit example.com">Link</a>One of the problems with the standard HTML implementation of the TITLE attribute is that this title content does not automatically appear on keyboard focus. We recommend that you use JavaScript to ensure that this information is always exposed on keyboard focus.

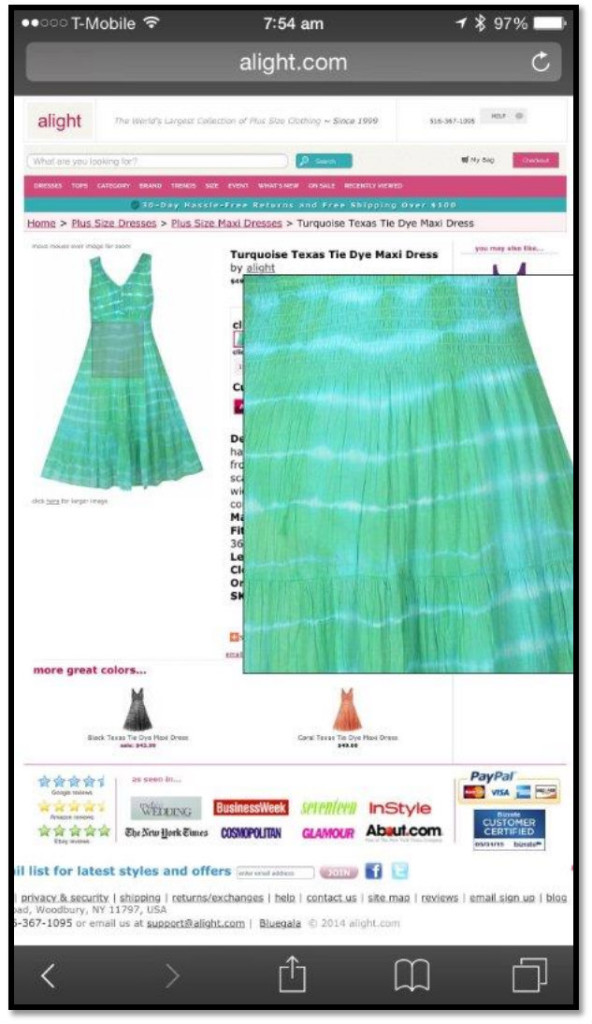

However, other sites take this functionality even further by providing a zoomed-in view of the site on mouse hover. This is commonly seen on websites selling clothing – hovering over a particular item provides a zoomed-in version of the clothing so you can easily see the patterns and fabric texture.

When the mouse leaves the item, the popup disappears. Often this functionality is not made available to the keyboard, but it does function on a mobile device; though, not in an accessible way.

In the example below, the user has activated the popup by touching the clothing item. This popup partially obscures other content in the site. However, as the site is being viewed on a mobile device there is no way to remove that focus, as you normally would do by moving your mouse to another area in the site.

The popup generally remains activated and cannot be dismissed by the user unless they close the browser entirely. We have called this a ‘mobile hover trap’. Even tapping on any other part of the screen is often not enough not close this popup.

Figure 3: Mobile hover trap: popup cannot be removed

Of course, sites built specifically for mobile are unlikely to have this error, as it is well-known that the hover effect can’t be replicated on mobile.

The Wrap Up..

These are just a couple of accessibility issues that are unique to mobile and are not covered properly in WCAG2. Although I commend the WCAG Working Group for an excellent discussion paper on mobile issues, I think that they need to go further and develop specific mobile techniques.

Related Reading:

Gian will be speaking on the topic of mobile and accessibility at:

- CodeMotion Berlin, Germany on the 2nd November

- StarTechConf in Santiago, Chile on the 6th November.

Footnotes

- https://www.w3.org/WAI/GL/wiki/Keyboard_interface ↩

- Mouse keys is a feature of some graphical user interfaces that uses the keyboard (especially numeric keypad) as a pointing device (usually replacing a mouse). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouse_keys ↩

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Mobile Accessibility Fails

What are some common mobile accessibility fails?

Mobile accessibility fails are common and can significantly impact the user experience. Some of the most common ones include small touch targets, lack of keyboard accessibility, poor color contrast, and lack of alternative text for images. These issues can make it difficult for users, especially those with disabilities, to navigate and interact with mobile applications and websites.

How can I test my mobile app for accessibility?

There are several tools available for testing mobile accessibility. These include automated tools like Google’s Lighthouse, manual testing tools like the Accessibility Inspector in iOS, and user testing with individuals who have disabilities. It’s important to use a combination of these methods to ensure your app is fully accessible.

What is WCAG and why is it important for mobile accessibility?

WCAG stands for Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. These guidelines provide a set of recommendations for making web content more accessible to people with disabilities. Following these guidelines can help ensure your mobile app or website is accessible to all users, including those with visual, auditory, physical, speech, cognitive, language, learning, and neurological disabilities.

What are some examples of mobile accessibility fails?

Examples of mobile accessibility fails can range from simple design oversights to more complex technical issues. For instance, a mobile app that doesn’t support screen readers would be inaccessible to visually impaired users. Similarly, an app that requires complex gestures or precise tapping may be difficult for users with motor impairments to use.

How can I improve the color contrast in my mobile app for better accessibility?

Improving color contrast can significantly enhance the accessibility of your mobile app. You can use tools like the Colour Contrast Analyser to check the contrast of your app. If the contrast is too low, consider adjusting your color scheme to make text and important elements stand out more clearly against the background.

What is the role of alternative text in mobile accessibility?

Alternative text, or alt text, provides a textual description of images and other non-text content. This is crucial for visually impaired users who rely on screen readers to understand the content. Without alt text, these users may miss out on important information conveyed through images.

How can I make my mobile app more keyboard-friendly?

Making your mobile app keyboard-friendly is an important aspect of accessibility. This can be achieved by ensuring all interactive elements can be accessed and activated using the keyboard alone. Additionally, providing clear focus indicators can help keyboard users navigate your app more easily.

What are some free mobile accessibility testing tools?

There are several free tools available for testing mobile accessibility. These include Google’s Lighthouse, WAVE, and the Accessibility Scanner for Android. These tools can help identify accessibility issues in your app and provide recommendations for improvements.

What are some of the greatest accessibility fails of all time?

Some of the greatest accessibility fails include websites and apps that are completely inaccessible to screen readers, lack of captions for videos, and websites that prevent users from resizing text. These fails not only create barriers for users with disabilities but can also lead to legal consequences for the organizations responsible.

How can I ensure my mobile app complies with accessibility guidelines?

Ensuring compliance with accessibility guidelines involves several steps. First, familiarize yourself with the guidelines, such as WCAG. Then, use a combination of automated and manual testing methods to identify any accessibility issues in your app. Finally, involve users with disabilities in your testing process to gain valuable insights into the user experience.

Gian Wild has been working in accessibility since 1998. She worked on the very first Australian accessible web site and was the accessibility consultant for the Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games. For six years she was actively involved in the W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Working Group. Gian Wild is the Director of AccessibilityOz.

Published in

·Accessibility·Design·Design & UX·Sketch·Technology·Typography·Usability·UX·February 25, 2016

Published in

·Accessibility·Animation·Animation·Design·Design & UX·Technology·Usability·UX·March 22, 2017

Published in

·Accessibility·Animation·Design·Design & UX·Technology·UI Design·Usability·UX·September 13, 2017