Modules are wonderfully flexible language constructs which can be applied to a wide variety of use cases, such as namespacing, inheritance, and decorating. However, some developers are still confused about how modules work and how they interact with their own code. This article aims to shed some light on Modules and their usage.

The Ruby Object Model (ROM)

As with most things Ruby, modules are very easy to use, once we understand how they fit into the Ruby Object Model (ROM). The ROM is populated by objects that are classes (class-objects, a.k.a. Classes) and objects that are instances of classes (instance-objects). Oh, and Modules too! Let’s create a couple of classes:

class Car

def drive

"driving"

end

end

class Trabant < Car

end

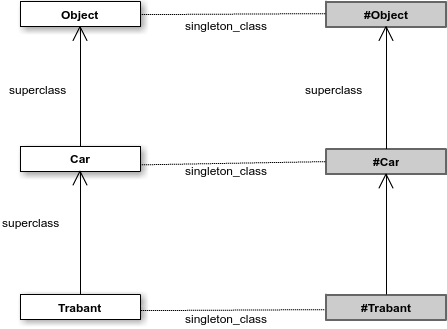

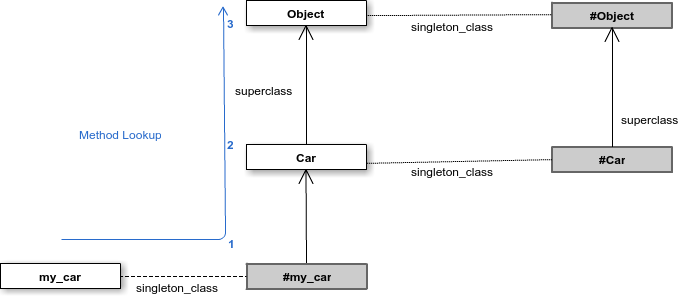

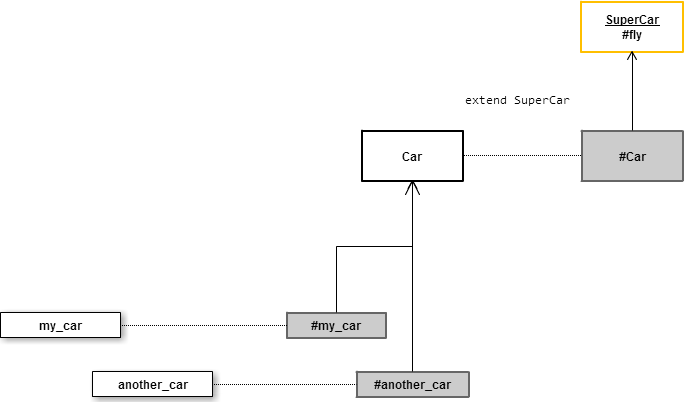

If we visualize the ROM on a 2D plain, then the object hierarchy looks like this:

The class-objects our class is derived from live above our class. The class-objects deriving from our class live below it. To the right of our class, lives its eigenclass (a.k.a singleton class or meta-class). Eigenclasses are class-objects, too, and as such, they have superclasses, usually the eigenclass of our class’s superclass or, in the case of instance objects, the class of the object itself. A full description of eigenclasses is beyond the scope of this article and deserves an article in itself. For now, don’t worry too much about them, just know that they are there and that they have a purpose.

So, what happens when we instantiate an object based on our class?

my_car = Car.new

Ruby will create our object’s eigenclass directly under our Car class. It will place our new instance (my_car) to the left of its eigenclass and outside the object hierarchy.

We can actually verify all this in Ruby’s irb:

my_car.class

=> Car

> my_car.singleton_class

=> #<Class:#<Car:0x0000000165e568>>

> my_car.singleton_class.class

=> Class

> my_car.singleton_class.superclass

=> Car

Method Lookup

Let’s call a method on our object?

my_car.drive

The object we call a method on (my_car) is called the receiver object. Ruby has a very simple algorithm for looking up methods:

receiver –> look to the right –> look up

When we call the drive method on my_car, Ruby will first look to the right in my_car‘s eigenclass object. It won’t find the method definition there, so it will look up to the Car objects, where it will find the definition of drive. Knowing this makes understanding how to use modules easy.

Modules in Their Environment

There are three things we can do with a module:

- Include it in our class-objects

- Prepend it to our class-objects

- Extend our class objects or instance objects with it

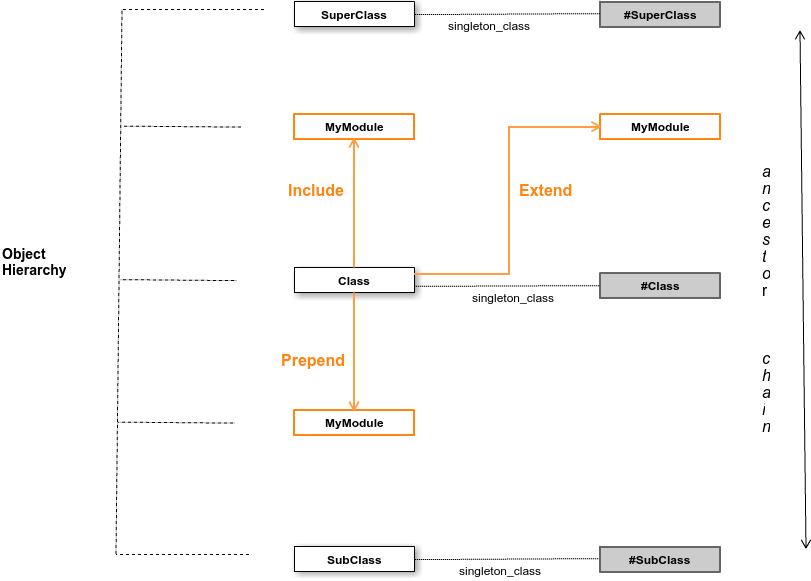

The Helicopter Rule

Ruby slots Modules into the ROM by following what I call the Helicopter rule. I call it that because in my warped imagination the diagram looks like a helicopter, as shown in the above image. The Helicopter Rule means:

- Including a module in our object will place it directly above our object.

- Prepending a module to our object will place it directly below our object.

- Extending our object with a module will place it directly above our object’s eigenclass.

Let’s verify this in code:

module A; end

module B; end

module C; end

class MyClass

include A

prepend B

extend C

end

MyClass.ancestors

=> [B, MyClass, A, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

MyClass.singleton_class.ancestors

=> [#<Class:MyClass>, C, #<Class:Object>, #<Class:BasicObject>, Class, Module, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

We observe that module A is placed directly above MyClass (included), module B is placed directly below MyClass (prepended) and module C is placed directly above MyClass‘s eigenclass (extended)

NOTE: Calling the superclass method on a class object will give us the next higher class in the ancestor chain above our class. However, as Modules aren’t technically Classes, superclass won’t show us any modules directly above our class. For that, we need to use the ancestors method.

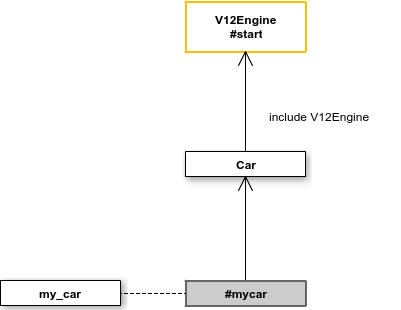

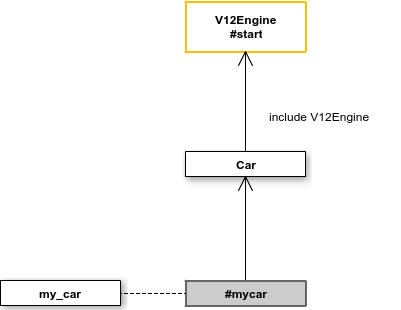

Including

Let’s open our Car class and include a Module:

module V12Engine

def start; "...roar!"; end

end

class Car

include V12Engine

end

When we include a module in our class, Ruby places it directly above our class. This means that when we call a method on our instance object, Ruby will find it in the object hierarchy and run it:

my_car.start

=> ...roar!"

This is the usual way to implement multiple inheritance in Ruby, as we can include many modules in our class, thereby giving it a lot of extra functionality. Modules used to that effect are known as “mixins”.

Note: It also means that if we define a method with the same name in our Car class, Ruby will find and run this instead and our Module method will never be called.

Prepending

When we prepend a module to our class, Ruby places it directly below our class. The means that, during method lookup, Ruby will encounter the methods defined in the Module before the methods defined in our Class. As a result, any module methods will effectively override any class methods with the same name. Let’s try this:

module ElectricEngine

def drive; "eco-driving!"; end

end

class Car

prepend ElectricEngine

end

my_car = Car.new

my_car.drive

=> eco-driving!

Observe that if we now call the drive method on my_car, we’re getting the prepended module’s implementation of the method, instead of the Car class implementation. Prepending modules can be very useful when we want to scope our method logic according to various external conditions. Say, for example, we want to measure our methods’ performance when running in a test environment. Instead of polluting our methods with if statements and instrumentation code, we can put our specialized methods in a separate module and prepend the module to our class only if we’re in a test environment:

module Instrumentable

require 'objspace'

def drive

puts ObjectSpace.count_objects[:FREE]

super

puts ObjectSpace.count_objects[:FREE]

end

end

class Car

prepend Instrumentable if ENV['RACK_ENV'] = 'test'

end

my_car = Car.new.drive

=> 711

=> driving

=> 678

Including and Prepending with Instances

As instance objects are placed outside the ROM hierarchy, there is no ‘above’ or ‘below’ them where we can place modules (see the Method Lookup diagram). This means that we cannot include or prepend modules to instance objects.

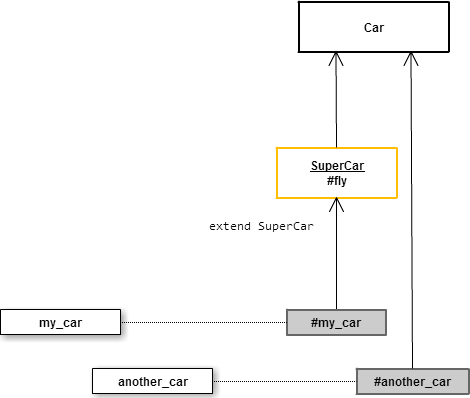

Extending Classes

When we extend our class object with a module, Ruby places it directly above our object’s eigenclass:

module SuperCar

def fly; "flying!"; end

end

class Car

extend SuperCar

end

Our Car instances can’t access the fly method, as the method lookup will start at the car instance, my_car, move right to the eigenclass my_car and then up to the Car class and its ancestors. The fly method will never be found in that path:

my_car.fly

=> NoMethodError: undefined method `fly' for #<Car:0x000000019ae8d0>

But what if we call the method on our class object instead?

Car.fly

=> flying

Our receiver object is now the Car class itself. Ruby will first look to the right (Car) and then up to SuperCar module where, lo and behold, it will find the fly method. So, extending a Class with a Module, effectively gives our Class new class methods.

Extending Instances

We can extend a specific instance of our Class, like so:

my_car.extend(SuperCar)

This will place the SuperCar module above our object’s eigen-class.

We can now call fly on our car:

my_car.fly

=> flying

But not on any other car:

another_car.fly

=> NoMethodError: undefined method `fly' for #<Car:0x000000012ae868>

Extending an instance object with a Module is a great way to dynamically decorate specific Class instances. I use it all the time in Rails applications to easily and quickly implement the Presenter pattern (i.e. model objects that I want to show in my views)

<%= my_article.extend(Presentable).title %>

Epilogue

There’s much more to Modules than can be covered in a single article. Understanding how Modules fit into the Ruby Object Model is essential in order to use them fully and creatively. Let us know how Modules fit into your designs and all the cool things you do with them!

Frequently Asked Questions about Ruby Modules

What is the difference between Ruby modules and classes?

In Ruby, both modules and classes are used to encapsulate methods, constants, and other data. The primary difference between them is that classes can be instantiated, while modules cannot. This means you can create an object from a class, but not from a module. Modules are typically used as a namespace or for mixin functionality, allowing you to add methods to multiple classes without repeating code.

How do I use a module in Ruby?

To use a module in Ruby, you first need to define it using the ‘module’ keyword, followed by the name of the module. Inside the module, you can define methods, constants, and other data. To use the methods or constants defined in a module, you can use the ‘include’ keyword in the class where you want to use them. This will make all methods from the module available as instance methods in the class.

What is the purpose of the ‘superclass’ method in Ruby?

The ‘superclass’ method in Ruby is used to get the parent class of a class. This is useful when you want to know the inheritance hierarchy of a class. The ‘superclass’ method returns the parent class, or ‘nil’ if the class has no parent (i.e., it’s a basic object or a module).

Can a Ruby module have instance variables?

Yes, a Ruby module can have instance variables. However, these variables are not shared among different instances of the class that includes the module. Each instance of the class will have its own copy of the module’s instance variables.

What is the ‘Class’ class in Ruby?

The ‘Class’ class in Ruby is the ultimate parent of all classes in Ruby. It provides a number of methods for creating and managing classes. For example, the ‘new’ method is used to create a new instance of a class, and the ‘superclass’ method is used to get the parent class of a class.

How do I create a subclass in Ruby?

To create a subclass in Ruby, you simply define a new class and specify the parent class after the ‘<‘ symbol. For example, ‘class Subclass < ParentClass’ would create a new subclass of ‘ParentClass’.

Can a Ruby class include multiple modules?

Yes, a Ruby class can include multiple modules. When a class includes multiple modules, it gains all the methods from all the included modules. If there are method name conflicts between modules, the last included module’s method will be used.

What is the difference between ‘include’ and ‘extend’ in Ruby?

The ‘include’ and ‘extend’ keywords in Ruby are used to add methods from a module to a class. The difference between them is that ‘include’ adds the methods as instance methods, while ‘extend’ adds them as class methods.

How do I check if a class includes a module in Ruby?

To check if a class includes a module in Ruby, you can use the ‘include?’ method on the class’s ancestors. For example, ‘ClassName.ancestors.include? ModuleName’ will return true if the class includes the module, and false otherwise.

Can a Ruby module include another module?

Yes, a Ruby module can include another module. This is known as module composition. When a module includes another module, it gains all the methods from the included module. This can be useful for organizing related methods into separate modules, and then combining them as needed.

Fred Heath

Fred HeathFred is a software jack of all trades, having worked at every stage of the software development life-cycle. He loves: solving tricky problems, Ruby, Agile methods, meta-programming, Behaviour-Driven Development, the semantic web. Fred works as a freelance developer, and consultant, speaks at conferences and blogs.