We sometimes come across some amazing posts in other locations, and with the permissions of their authors, repost them on SitePoint. This is one such instance. In the post below, Thomas Punt implements the range operator in PHP. If you’ve ever been interested in PHP internals and adding features to your favorite programming language, now’s the time to learn!

This article assumes that the reader is able to build PHP from source. If this is not the case, then please see the Building PHP chapter of the PHP Internals Book first.

This article will demonstrate how to implement a new operator in PHP. The following steps will be taken to do this:

- Updating the lexer: This will make it aware of the new operator syntax so that it can be turned into a token

- Updating the parser: This will say where it can be used, as well as what precedence and associativity it will have

- Updating the compilation stage: This is where the abstract syntax tree (AST) is traversed and opcodes are emitted from it

- Updating the Zend VM: This is used to handle the interpretation of the new opcode for the operator during script execution

This article therefore seeks to provide a brief overview of a number of PHP’s internal aspects.

Also, a big thank you to Nikita Popov for proofreading and helping to improve my article!

The Range Operator

The operator that will be added into PHP in this article will be called the range operator (|>). To keep things simple, the range operator will be defined with the following semantics:

- The incrementation step will always be one

- Both operands must either be integers or floats

- If min = max, return a one element array consisting of min.

(The above points will all be referenced in the final section, Updating the Zend VM, when we finally implement the above semantics.)

If any of the above semantics are not satisfied, then an Error exception will be thrown. This will therefore occur if:

- either operand is not an integer or float

- min > max

- the range (max – min) is too large

Examples:

1 |> 3; // [1, 2, 3]

2.5 |> 5; // [2.5, 3.5, 4.5]

$a = $b = 1;

$a |> $b; // [1]

2 |> 1; // Error exception

1 |> '1'; // Error exception

new StdClass |> 1; // Error exception

Updating the Lexer

Firstly, the new token must be registered in the lexer so that when the source code is tokenized, it will turn |> into the T_RANGE token. For this, the Zend/zend_language_scanner.l file will need to be updated by adding the following code to it (where all of the other tokens are defined, line ~1200):

<ST_IN_SCRIPTING>"|>" {

RETURN_TOKEN(T_RANGE);

}

The ST_IN_SCRIPTING mode is the state the lexer is currently in. This means it will only match the |> character sequence when it is in normal scripting mode. The code between the curly braces is C code that will be executed when |> is found in the source code. In this example, it simply returns a T_RANGE token.

Note: Since we’re modifying the lexer, we will need Re2c to regenerate it. This

dependency is not needed for normal builds of PHP.

Next, the T_RANGE identifier must be declared in the Zend/zend_language_parser.y file. To do this, we must add the following line to where the other token identifiers are declared (at the end will do, line ~220):

%token T_RANGE "|> (T_RANGE)"

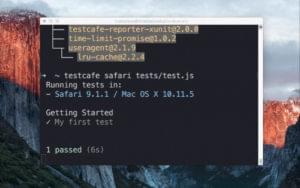

PHP now recognizes the new operator:

1 |> 2; // Parse error: syntax error, unexpected '|>' (T_RANGE) in...

But since its usage hasn’t been defined yet, using it will lead to a parse error. This will be fixed in the next section.

First though, we must regenerate the ext/tokenizer/tokenizer_data.c file in the tokenizer extension to cater for the newly added token. (The tokenizer extension simply provides an interface for PHP’s lexer to userland through the token_get_all and token_name functions.) At the moment, it is blissfully ignorant of our new T_RANGE token:

echo token_name(token_get_all('<?php 1|>2;')[2][0]); // UNKNOWN

We regenerate the ext/tokenizer/tokenizer_data.c file by going into the ext/tokenizer directory and executing the tokenizer_data_gen.sh file. Then go back into the root php-src directory and build PHP again. Now the tokenizer extension works again:

echo token_name(token_get_all('<?php 1|>2;')[2][0]); // T_RANGE

Updating the Parser

The parser needs to be updated now so that it can validate where the new T_RANGE token is used in PHP scripts. It’s also responsible for stating the precedence and associativity of the new operator and generating the abstract syntax tree (AST) node for the new construct. This will all be done in the Zend/zend_language_parser.y grammar file, which contains the token definitions and production rules that Bison will use to generate the parser from.

Digression:

Precedence determines the rules of grouping expressions. For example, in the expression 3 + 4 * 2, * has a higher precedence than +, and so it will be grouped as 3 + (4 * 2).

Associativity is how the operator will behave when chained. It determines whether the operator can be chained, and if so, then what direction it will be grouped from in a particular expression. For example, the ternary operator has (rather strangely) left-associativity, and so it will be grouped and executed from left to right. Therefore, the following expression:

1 ? 0 : 1 ? 0 : 1; // 1

Will be executed as follows:

(1 ? 0 : 1) ? 0 : 1; // 1

This can, of course, be changed (read: rectified) to be right-associative with proper grouping:

$a = 1 ? 0 : (1 ? 0 : 1); // 0

Some operators, however, are non-associative and therefore cannot be chained at all. For example, the less than (>) operator is like this, and so the following is invalid:

1 < $a < 2;

Since the range operator will evaluate to an array, having it as an input operand to itself would be rather useless (i.e. 1 |> 3 |> 5 would be non-sensical). So let’s make the operator non-associative, and whilst we’re at it, let’s set it to have the same precedence as the combined comparison operator (T_SPACESHIP). This is done by adding the T_RANGE token onto the end of the following line (line ~70):

%nonassoc T_IS_EQUAL T_IS_NOT_EQUAL T_IS_IDENTICAL T_IS_NOT_IDENTICAL T_SPACESHIP T_RANGE

Next, we must update the expr_without_variable production rule to cater for our new operator. This will be done by adding the following code into the rule (I placed it just below the T_SPACESHIP rule, line ~930):

| expr T_RANGE expr

{ $$ = zend_ast_create(ZEND_AST_RANGE, $1, $3); }

The pipe character (|) is used to denote an or, meaning that any one of those rules can match in that particular production rule. The code within the curly braces is to be executed when that match occurs. The $$ denotes the result node that stores the value of the expression. The zend_ast_create function is used to create our AST node for our operator. This AST node is created with the name ZEND_AST_RANGE, and has two values: $1 references the left operand (expr T_RANGE expr) and $3 references the right operand (expr T_RANGE expr).

Next, we will need to define the ZEND_AST_RANGE constant for the AST. To do this, the Zend/zend_ast.h file will need to be updated by simply adding the ZEND_AST_RANGE constant under the list of two children nodes (I added it under ZEND_AST_COALESCE):

ZEND_AST_RANGE,

Now executing our range operator will just cause the interpreter to hang:

1 |> 2;

It’s time to update the compilation stage.

Updating the Compilation Stage

We now need to update the compilation stage. The parser outputs an AST that is then recursively traversed, where functions are triggered to execute as each node in the AST is visited. These triggered functions emit opcodes that the Zend VM will then execute later during the interpretation phase.

This compilation happens in Zend/zend_compile.c , so let’s start by adding our new AST node name (ZEND_AST_RANGE) into the large switch statement in the zend_compile_expr function (I’ve added it just below ZEND_AST_COALESCE, line ~7200):

case ZEND_AST_RANGE:

zend_compile_range(result, ast);

return;

Now we must define the zend_compile_range function somewhere in that same file:

void zend_compile_range(znode *result, zend_ast *ast) /* {{{ */

{

zend_ast *left_ast = ast->child[0];

zend_ast *right_ast = ast->child[1];

znode left_node, right_node;

zend_compile_expr(&left_node, left_ast);

zend_compile_expr(&right_node, right_ast);

zend_emit_op_tmp(result, ZEND_RANGE, &left_node, &right_node);

}

/* }}} */

We start by dereferencing the left and right operands of the ZEND_AST_RANGE node into the pointer variables left_ast and right_ast. We then define two znode variables that will hold the result of compiling down the AST nodes for both of the operands (this is the recursive part of traversing the AST and compiling its nodes into opcodes).

Next, we emit the ZEND_RANGE opcode with its two operands using the zend_emit_op_tmp function.

Now would probably be a good time to quickly discuss opcodes and their types to better explain the usage of the zend_emit_op_tmp function.

Opcodes are instructions that are executed by the Zend VM. They each have:

- a name (a constant that maps to some integer)

- an op1 node (optional)

- an op2 node (optional)

- a result node (optional). This is usually used to store a temporary value of the opcode operation

- an extended value (optional). This is an integer value that is used to differentiate between behaviours for overloaded opcodes

Digression:

The opcodes for a PHP script can be seen using either:

- PHPDBG:

sapi/phpdbg/phpdbg -np* program.php - Opcache

- Vulcan Logic Disassembler (VLD) extension:

sapi/cli/php -dvld.active=1 program.php - Or, if the script is short and trivial, then 3v4l can be used

Opcode nodes (znode_op structures) can be of a number of different types:

IS_CV– for Compiled Variables. These are simple variables (like$a) that are cached in a simple array to bypass hash table lookups. They were introduced in PHP 5.1 under the Compiled Variables optimisation. They’re denoted by!nin VLD (where n is an integer)IS_VAR– for all other variable-like expressions that aren’t simple (like$a->b). They can hold anIS_REFERENCEzval, and are denoted by$nin VLD (where n is an integer)IS_CONST– for literal values (e.g. hard-coded strings)IS_TMP_VAR– temporary variables are used to hold the intermediate result of an expression (making them typically short-lived). They too can be refcounted (as of PHP 7), but cannot hold anIS_REFERENCEzval (because temporary values cannot be used as references). They are denoted by~nin VLD (where n is an integer)IS_UNUSED– generally used to mark an op node as not used. Sometimes, however, data will be stored in theznode_op.nummember to be used in the VM.

This brings us back to the above zend_emit_op_tmp function, which will emit a zend_op with a type of IS_TMP_VAR. We want to do this because our operator will be an expression, and so the value it produces (an array) will be a temporary variable that may be used as an operand to another opcode (such as ASSIGN from code like $var = 1 |> 3;).

Updating the Zend VM

Now we will need to update the Zend VM to handle the execution of our new opcode. This will involve updating the Zend/zend_vm_def.h file by adding the following code (at the bottom will do):

ZEND_VM_HANDLER(182, ZEND_RANGE, CONST|TMP|VAR|CV, CONST|TMP|VAR|CV)

{

USE_OPLINE

zend_free_op free_op1, free_op2;

zval *op1, *op2, *result, tmp;

SAVE_OPLINE();

op1 = GET_OP1_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF(BP_VAR_R);

op2 = GET_OP2_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF(BP_VAR_R);

result = EX_VAR(opline->result.var);

// if both operands are integers

if (Z_TYPE_P(op1) == IS_LONG && Z_TYPE_P(op2) == IS_LONG) {

// for when min and max are integers

} else if ( // if both operands are either integers or doubles

(Z_TYPE_P(op1) == IS_LONG || Z_TYPE_P(op1) == IS_DOUBLE)

&& (Z_TYPE_P(op2) == IS_LONG || Z_TYPE_P(op2) == IS_DOUBLE)

) {

// for when min and max are either integers or floats

} else {

// for when min and max are neither integers nor floats

}

FREE_OP1();

FREE_OP2();

ZEND_VM_NEXT_OPCODE_CHECK_EXCEPTION();

}

(The opcode number should be one more than the previous highest, so 182 may already be taken for you. To quickly see what the highest current opcode number is, look at the bottom of the Zend/zend_vm_opcodes.h file – the ZEND_VM_LAST_OPCODE constant should hold this value.)

Digression:

The above code contains a number of pseudo-macros (like USE_OPLINE and GET_OP1_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF). These aren’t actual C macros – instead, they’re replaced by the Zend/zend_vm_gen.php script during VM generation, as opposed to by the preprocessor during source code compilation. Therefore, if you’d like to look up their definitions, you’ll need to dig through the Zend/zend_vm_gen.php file.

The ZEND_VM_HANDLER pseudo-macro contains each opcode’s definition. It can have 5 parameters:

- The opcode number (182)

- The opcode name (ZEND_RANGE)

- The valid left operand types (CONST|TMP|VAR|CV) (see

$vm_op_decodein Zend/zend_vm_gen.php for all types) - The valid right operand types (CONST|TMP|VAR|CV) (ditto)

- An optional flag holding the extended value for overloaded opcodes (see

$vm_ext_decodein Zend/zend_vm_gen.php for all types)

From our above definitions of the types, we can see that:

// CONST enables for

1 |> 5.0;

// TMP enables for

(2**2) |> (1 + 3);

// VAR enables for

$cmplx->var |> $var[1];

// CV enables for

$a |> $b;

If one or both operands are not used, then they are marked with ANY.

Note that TMPVAR was introduced into ZE3 and is similar to TMP|VAR in that it handles the same opcode node types, but differs in what code is generated. TMPVAR generates a single method to handle both TMP and VAR, which decreases the VM size but requires more conditional logic. Conversely, TMP|VAR generates methods for both of TMP and VAR, increasing the VM size but with less conditionals.

Moving onto the body of our opcode definition, we begin by invoking the USE_OPLINE pseudo-macro to declare the opline variable (a zend_op struct). This will be used to fetch the operands (with pseudo-macros like GET_OP1_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF) and setting the return value of the opcode.

Next, we declare two zend_free_op variables. These are simply pointers to zvals that are declared for each operand we use. They are used when checking if that particular operand needs to be freed. Four zval variables are then declared. op1 and op2 are pointers to zvals that hold the operand values. result is declared to store the result of the opcode operation. Lastly, tmp is used as an intermediary value of the range looping operation that will be copied upon each iteration into a hash table.

The op1 and op2 variables are then initialized by the GET_OP1_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF and GET_OP2_ZVAL_PTR_DEREF pseudo-macros, respectively. These pseudo-macros are also responsible for initializing the free_op1 and free_op2 variables. The BP_VAR_R constant that is passed into the aforementioned macros is a type flag. It stands for BackPatching Variable Read and is used when fetching compiled variables. Lastly, the opline’s result is dereferenced and assigned to result, to be used later on.

Let’s now fill in the first if body when both min and max are integers:

zend_long min = Z_LVAL_P(op1), max = Z_LVAL_P(op2);

zend_ulong size, i;

if (min > max) {

zend_throw_error(NULL, "Min should be less than (or equal to) max");

HANDLE_EXCEPTION();

}

// calculate size (one less than the total size for an inclusive range)

size = max - min;

// the size cannot be greater than or equal to HT_MAX_SIZE

// HT_MAX_SIZE - 1 takes into account the inclusive range size

if (size >= HT_MAX_SIZE - 1) {

zend_throw_error(NULL, "Range size is too large");

HANDLE_EXCEPTION();

}

// increment the size to take into account the inclusive range

++size;

// set the zval type to be a long

Z_TYPE_INFO(tmp) = IS_LONG;

// initialise the array to a given size

array_init_size(result, size);

zend_hash_real_init(Z_ARRVAL_P(result), 1);

ZEND_HASH_FILL_PACKED(Z_ARRVAL_P(result)) {

for (i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

Z_LVAL(tmp) = min + i;

ZEND_HASH_FILL_ADD(&tmp);

}

} ZEND_HASH_FILL_END();

ZEND_VM_NEXT_OPCODE_CHECK_EXCEPTION();

We start by defining the min and max variables. These are declared as zend_long, which must be used when declaring long integers (likewise with zend_ulong for defining unsigned long integers). This size is then declared as zend_ulong, which will hold the size of the array to be generated.

A check is then performed to see if min is greater than max – if it is, an Error exception is thrown. By passing in NULL as the first argument to zend_throw_error, the exception class defaults to Error. We could specialise this exception by sub-classing Error and make a new class entry in Zend/zend_exceptions.c, but that’s probably best covered in a later article. If an exception is thrown, then we invoke the HANDLE_EXCEPTION pseudo-macro that skips onto the next opcode to be executed.

Next, we calculate the size of the array to be generated. This size is one less than the actual size because it does not take into account the inclusive range. The reason why we don’t simply plus one onto this size is because of the potential for overflow to occur if min is equal to ZEND_LONG_MIN (PHP_INT_MIN) and max is equal to ZEND_LONG_MAX (PHP_INT_MAX).

The size is then checked against the HT_MAX_SIZE constant to ensure that the array will fit inside of the hash table. The total array size must not be greater than or equal to HT_MAX_SIZE – if it is, then we once again throw an Error exception and exit the VM.

Because HT_MAX_SIZE is equal to INT_MAX + 1, we know that if size is less than this, we can safely increment size without fear of overflow. So this is what we do next so that our size now accommodates for an inclusive range.

We then change the type of the tmp zval to IS_LONG, and then initialise result using the array_init_size macro. This macro basically sets the type of result to IS_ARRAY_EX, allocates memory for the zend_array structure (a hashtable), and sets up its corresponding hashtable. The zend_hash_real_init function then allocates memory for the Bucket structures that hold each of the elements of the array. The second argument, 1, specifies that we would like it to be a packed hashtable.

Digression:

A packed hashtable is effectively an actual array, i.e. one that is numerically accessed via integer keys (unlike typical associative arrays in PHP). This optimization was introduced into PHP 7 because it was recognized that many arrays in PHP were integer indexed (keys in increasing order). Packed hashtables allow the hashtable buckets to be directly accessed (like a normal array). See Nikita’s PHP’s new hashtable implementation article for more information.

Note: The _zend_array structure has two aliases: zend_array and HashTable.

Next, we populate the array. This is done with the ZEND_HASH_FILL_PACKED macro (definition), which basically keeps track of the current bucket to insert into. The tmp zval stores the intermediary result (the array element) when generating the array. The ZEND_HASH_FILL_ADD macro makes a copy of tmp, inserts this copy into the current hashtable bucket, and increments to the next bucket for the next iteration.

Finally, the ZEND_VM_NEXT_OPCODE_CHECK_EXCEPTION macro (introduced in ZE3 to replace the separate CHECK_EXCEPTION() and ZEND_VM_NEXT_OPCODE() calls made in ZE2) checks whether an exception has occurred. Provided an exception hasn’t occurred, then the VM skips onto the next opcode.

Let’s now take a look at the else if block:

long double min, max, size, i;

if (Z_TYPE_P(op1) == IS_LONG) {

min = (long double) Z_LVAL_P(op1);

max = (long double) Z_DVAL_P(op2);

} else if (Z_TYPE_P(op2) == IS_LONG) {

min = (long double) Z_DVAL_P(op1);

max = (long double) Z_LVAL_P(op2);

} else {

min = (long double) Z_DVAL_P(op1);

max = (long double) Z_DVAL_P(op2);

}

if (min > max) {

zend_throw_error(NULL, "Min should be less than (or equal to) max");

HANDLE_EXCEPTION();

}

size = max - min;

if (size >= HT_MAX_SIZE - 1) {

zend_throw_error(NULL, "Range size is too large");

HANDLE_EXCEPTION();

}

// we cast the size to an integer to get rid of the decimal places,

// since we only care about whole number sizes

size = (int) size + 1;

Z_TYPE_INFO(tmp) = IS_DOUBLE;

array_init_size(result, size);

zend_hash_real_init(Z_ARRVAL_P(result), 1);

ZEND_HASH_FILL_PACKED(Z_ARRVAL_P(result)) {

for (i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

Z_DVAL(tmp) = min + i;

ZEND_HASH_FILL_ADD(&tmp);

}

} ZEND_HASH_FILL_END();

ZEND_VM_NEXT_OPCODE_CHECK_EXCEPTION();

Note: We use long double to handle the cases where there is potentially a mix of floats and integers as operands. This is because double only has 53 bits of precision, and so any integer greater than 2^53 may not be accurately represented as a double. long double, on the other hand, has at least 64 bits of precision, and so it can therefore accurately represent 64 bit integers.

This code is very similiar to the previous logic. The main difference now is that we handle the data as floating point numbers. This includes fetching them with the Z_DVAL_P macro, setting the type info for tmp to IS_DOUBLE, and inserting the zval (of type double) with the Z_DVAL macro.

Lastly, we must handle the case where either (or both) min and max are not integers or floats. As defined in point #2 of our range operator semantics, only integers and floats are supported as operands – if anything else is provided, an Error exception will be thrown. Paste the following code in the else block:

zend_throw_error(NULL, "Unsupported operand types - only ints and floats are supported");

HANDLE_EXCEPTION();

With our opcode definition done, we must now regenerate the VM. This is done by running the Zend/zend_vm_gen.php file, which will use the Zend/zend_vm_def.h file to regenerate the Zend/zend_vm_opcodes.h, Zend/zend_vm_opcodes.c, and Zend/zend_vm_execute.h files.

Now build PHP again so that we can see the range operator in action:

var_dump(1 |> 1.5);

var_dump(PHP_INT_MIN |> PHP_INT_MIN + 1);

Outputs:

array(1) {

[0]=>

float(1)

}

array(2) {

[0]=>

int(-9223372036854775808)

[1]=>

int(-9223372036854775807)

}

Now our operator finally works! We’re not quite done yet, though. We still need to update the AST pretty printer (that turns the AST back to code). It currently does not support our range operator – this can be seen by using it within assert():

assert(1 |> 2); // segfaults

Note that assert() uses the pretty printer to output the expression being asserted as part of its error message upon failure. This is only done when the asserted expression is not in string form (since the pretty printer would not be needed otherwise), and is something that is new to PHP 7.

To rectify this, we simply need to update the [Zend/zend_ast.c] (http://lxr.php.net/xref/PHP_7_0/Zend/zend_ast.c) file to turn our ZEND_AST_RANGE node into a string. We will firstly update the precedence table comment (line ~520) by specifying our new operator to have a priority of 170 (this should match the zend_language_parser.y file):

* 170 non-associative == != === !== |>

Next, we need to insert a case statement in the zend_ast_export_ex function to handle ZEND_AST_RANGE (just above case ZEND_AST_GREATER):

case ZEND_AST_RANGE: BINARY_OP(" |> ", 170, 171, 171);

case ZEND_AST_GREATER: BINARY_OP(" > ", 180, 181, 181);

case ZEND_AST_GREATER_EQUAL: BINARY_OP(" >= ", 180, 181, 181);

The pretty printer has been updated now and assert() works fine once again:

assert(false && 1 |> 2); // Warning: assert(): assert(false && 1 |> 2) failed...

Conclusion

This article has covered a lot of ground, albeit thinly. It has shown the stages ZE goes through when running PHP scripts, how these stages interoperate with one-another, and how we can modify each of these stages to include a new operator into PHP. This article demonstrated just one possible implementation of the range operator in PHP – I’ll cover an alternative (and better) implementation in the followup.

Frequently Asked Questions about Implementing the Range Operator in PHP

What is the range operator in PHP and why is it important?

The range operator in PHP is a built-in function that creates an array containing a range of elements. It’s important because it allows developers to generate sequences of numbers or characters without having to manually create an array. This can be particularly useful in loops and other repetitive tasks, making your code more efficient and easier to read.

How do I use the range operator in PHP?

To use the range operator in PHP, you simply call the range function with two or three arguments. The first two arguments define the start and end of the range, and the optional third argument defines the step value. For example, range(0, 10, 2) would generate an array with the numbers 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10.

Can I use the range operator with letters as well as numbers?

Yes, the range operator in PHP can be used with both numbers and letters. When used with letters, it generates an array with a range of characters. For example, range('a', 'd') would generate an array with the letters ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’.

What happens if I use the range operator with a start value greater than the end value?

If you use the range operator with a start value greater than the end value, PHP will return an empty array. This is because the function cannot generate a sequence that decreases in value.

Can I use negative numbers with the range operator?

Yes, you can use negative numbers with the range operator in PHP. For example, range(-10, -5) would generate an array with the numbers -10, -9, -8, -7, -6, -5.

How can I use the range operator in a for loop?

You can use the range operator in a for loop by using the generated array as the iterable object. For example, foreach(range(0, 10) as $number) { echo $number; } would print the numbers 0 through 10.

What is the performance impact of using the range operator?

The range operator in PHP is generally quite efficient, but it can consume a lot of memory if used to generate large arrays. Therefore, it’s best to use it judiciously, especially in memory-sensitive applications.

Can I use the range operator with floating point numbers?

Yes, you can use the range operator with floating point numbers. However, due to the way floating point numbers are represented in computers, the results may not always be as expected.

How can I reverse the order of the array generated by the range operator?

You can reverse the order of the array generated by the range operator by using the array_reverse function. For example, array_reverse(range(0, 10)) would generate an array with the numbers 10 through 0.

Can I use the range operator to generate an array of dates?

No, the range operator in PHP cannot be used to generate an array of dates. However, you can achieve this by using a loop and the DateTime class.

Thomas is a recently graduated Web Technologies student from the UK. He has a vehement interest in programming, with particular focus on server-side web development technologies (specifically PHP and Elixir). He contributes to PHP and other open source projects in his free time, as well as writing about topics he finds interesting.