You Don’t Know Jack About Firefox!

If you feel that the Web has lost its sparkle, that’s probably because you’re slogging across it in an old browser. I’m over here on the other side, and the grass is not only greener: there are none of those microscopic grass bugs that cause nasty rashes!

Firefox Secrets

This excerpt is taken from Firefox Secrets, SitePoint’s new release, by Cheah Chu Yeow. Firefox is revolutionizing the way people browse the Web. Don’t get left behind: grab yourself a copy of Firefox Secrets and be part of the revolution!

The title contains over 290 pages of Firefox tips, tricks and hacks, providing invaluable pointers to help you customize the browser to your specfic preferences.

It starts with some of the better-known tweaks, such as search customizations and favourites, password, and history management. But later chapters challenge even the most hardened Firefox devotee, revealing the inner workings of Web developer extensions, RSS feed subscripton, and the little-known about:config interface.

This sample should give you a taste of the action. It begins at Chapter 2, Essential Browsing Features, which outlines the must-have functionality that any Firefox user should use to their advantage. We then skip to samples from Chapter 6, Tips, Tricks, and Hacks, and Chapter 7, Web Development Nirvana, through which you can roll up your sleeves and get your hands dirty tweaking the behind-the-scenes capabilities of this powerful browser. To find out more about Firefox Secrets, visit the book’s information page, or review the contents of the entire publication. As always, you can download this excerpt as a PDF if you prefer. And now, to Chapter 2.

Chapter 2. Essential Browsing Features

This chapter is all about moving forward to browse the Web with a new sense of style. We’ll investigate the major features of Firefox and I’ll show you how to use them. You’ll learn how to explore the Web more efficiently, and with fewer interruptions. You’ll also see how you might (if you so choose) let go of a few old Web surfing habits that may be holding you back; window management habits and Web search habits are two very important examples. There may even be pictures of attractive models, both male and female. Okay, there are no models. Let’s explore Firefox!

Tabbed Browsing

Tabbed browsing has been called “the best thing since sliced bread and the biggest fundamental improvement in Web browsing in years,” by Walter S. Mossberg, Staff Reporter of The Wall Street Journal. It has also been criticized, rejected and labeled a useless non-innovation. You must be wondering what the big deal is with tabbed browsing and which point of view is right. You might also be curious about which side of the argument I, your intrepid author who pretends to know what’s best for you, am on. You’ll find out soon enough!

If you’re a stranger to tabbed browsing, you’re probably trapped in a somewhat old-fashioned Web surfing pattern. Perhaps you click on an interesting link, wait for that link to load, then press the Back button when you’ve finished reading that new page. Alternatively, perhaps you right-click (or context-click on Mac OS X) on a hyperlink and select Open in New Window on those occasions when you don’t have time to wait for the new page to load.

Either way, prepare to be blown away when you see how effectively tabbed browsing eliminates waiting and unnecessary backwards and forwards tracking. You’ll be wondering how you could ever have been satisfied browsing one Web page at a time in a single window. Those who have already made the leap may still need some convincing as to why tabbed browsing is better than browsing with multiple windows. I’m here to encourage you to consider the benefits.

Let’s learn everything about use of tabbed browsing in Firefox. But remember: you are not forced to use it. If you’re more comfortable with a single window per Web page, then that’s your choice. Don’t deny yourself the possibility of a better alternative, though.

A Short History and a Warning

Tabbed browsing is not that new an idea; in fact, it wasn’t invented by Firefox. It’s probable that NetCaptor, a third-party program that provides an alternative tabbed browsing interface for Internet Explorer, pioneered this approach. The Mozilla Application Suite followed hot on the heels of that tool, and more recently, Opera has, too. Opera developed a Multiple Document Interface (MDI), which is not the same as the Tabbed Document Interface (TDI) of tabbed browsing; Opera has added a faux-tabbed browsing interface in Opera 7.60 preview 3 (and later). Firefox, being a derivative of the Mozilla Application Suite, naturally inherited its tabbed browsing capability. Of course, spreadsheet tools like Microsoft Excel have used tabs in the worksheet display area for a long time.

Currently, most graphical browsers support tabbed browsing. A quick (and incomplete) list of tab-enabled browsers reads: Firefox, Opera, Mozilla, Safari, Konqueror, Netscape, OmniWeb, and Camino. This list doesn’t include programs like NetCaptor, Maxthon, Avant Browser, and Crazy Browser, which add tabbed browsing functionality to Internet Explorer. The only notable exception is Internet Explorer itself, which may possibly be feature-enhanced with tabs in version 7.0.

It’s important to realize that the add-ons that provide tabbed browsing functionality in Internet Explorer (such as the aforementioned NetCaptor, Maxthon, and kin) carry the same faults as the Internet Explorer engine, since they are no more than superficial “skins” over this product. This means that, when you use one of these variant browsers, you remain open to the set of security risks implied by Internet Explorer.

Tabs vs. Multiple Windows

Here I am, stepping onto my soapbox and making the case for tabbed browsing against the alternative: multiple browser windows. Naturally, I’ll use Internet Explorer as the prime example for the case of multiple browser windows, since it’s the most popular tab-free browser. I’ll make objective arguments (I hope!) for both tabbed browsing and multiple windows, and leave it to you to make the decision as to which option suits you best.

Organizational Differences

Tabbed browsing doesn’t prevent the use of multiple windows; in fact, you can opt to use a browser that supports tabbed browsing in the same way as you use Internet Explorer (i.e. displaying a single window per Web page). You can use this compatibility to your advantage, mixing and matching both styles to suit your needs. Tabbed browsing groups related tabs in a single window, so you can have one window of tabs for work, another window for email and personal stuff, and so on. Tabbed browsing also lets you keep related tabs in a logical group. Multiple windows, on the other hand, are just that: a single window displays a single Web page.

There’s not much I can say to help the old-style multiple window case, even though I want to be objective. One small advantage is that closing a non-tabbed window dismisses only the single page it displays. Closing a tabbed window can dismiss a whole set of pages, some of which you may have meant to keep.

Managing Multiple Web Pages

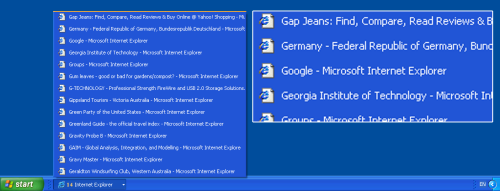

It’s second nature for most of us to work with multiple windows simultaneously. Naturally, we expect that those windows can be operated in a manageable way, but the crunch really comes when we have a large number of Web pages open. Does Figure 2.1 below, which shows the Windows taskbar, look manageable to you? There are 14 browser windows open!

Figure 2.1. Using multiple browser windows in IE.

I know I’d have a hard time finding the Web page I wanted here, particularly as each taskbar button shows the same unhelpful Internet Explorer icon. One solution, of course, is to use the “Group similar taskbar buttons” option that’s available on Windows XP; Linux KDE and Gnome users have an equivalent feature. Grouping helps – at least you can see the page titles, as shown in Figure 2.2. Personally, though, I dislike this feature because it requires me to click twice to reach the particular window I want.

Figure 2.2. Grouping IE windows makes browsing slightly easier.

In my view, tabs are a better solution. Figure 2.3 shows the same Web pages opened in tabs in Firefox.

Tabbed browsing suffers the same page title truncation problem as the taskbar, although a few more letters show in the given tab space. But, with the same number of windows open, it’s still hard to work out which page is the one I want. At least the tabs display helpful icons (called favicons) for Websites that provide them. You can see that about half of the tabs displayed in Figure 2.3 have favicons.

Figure 2.3. Multiple tabs displaying in Firefox.

Another redeeming feature of tabbed browsing is that this system allows you to juggle more Web pages than would be possible using multiple separate windows. You can handle more Web pages because there’s no competition for space on the tab bar (the section of the display that holds the tab names and icons). Multiple window browsing requires each IE window to compete with other open programs for space on the taskbar. That includes non-IE windows, the system notification area at the bottom right, the Start bar, the Quick Launch bar, and any other bars you may happen to have configured.

Which solution stands out? Well, both have merits. Firefox helpfully displays an indicative icon (a favicon) for different Websites, which, to my mind, is much more helpful than the showing the same “e” icon for every page. These displays vary a little between the Macintosh and Linux desktop environments, but I’m sure you get the picture.

Avoiding Context Pollution

There is a little issue I like to call “context-switching pollution.” Application context-switching occurs when you switch from one window to another on the desktop. My apologies to techies for this simplification and my abuse of the term “context-switching.” In Windows, you do that by clicking on a taskbar item, or by pressing Alt-Tab to bring up another window. Mac OS X users are probably big fans of Exposé. In Linux, depending on your Desktop Environment, you may have Windows-like Alt-Tab context-switching, or even an Exposé-like feature. When you context-switch, Windows displays an icon (a context object) for each available window; you then pick the one you want.

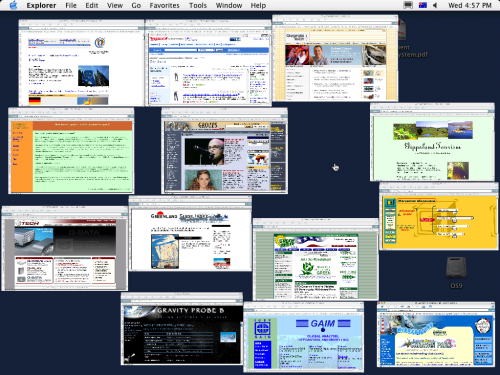

Now, if you have tabbed browsing in place, you’ll probably have a few windows open at most. In fact, most of the Firefox users I know have no need for more than a single window to hold all their tabs. I usually stick to a single window, myself. You can open as many tabs as you want within a window, and the bonus you receive is this: you have just one context object for that set of tabs. One window: one context object. By comparison, imagine that you have multiple IE windows open: one for each Web page. Each of these windows counts as a context object. And you have a bad case of context-switching pollution, my friend! Figure 2.4 shows what context-switching pollution looks like.

Figure 2.4. Context-switching pollution in Windows XP.

How are we ever going to quickly find the window we want without some furious Windows-style Alt-Tabbing? Figure 2.5 shows a similarly cluttered summary delivered by Exposé on Mac OS X.

Although Exposé fares better than the Windows context-switcher, you’re still left to perform laborious squint-and-click selection.

Tabbed browsing reduces those nasty multiple windows into individual tabs in a single window – two or three windows at most. Bye-bye, context-switching clutter!

Productivity Differences

When you read a Web page in a tabbed browser, you can open interesting links in “background” tabs, which will load those pages as you continue to read the original. You can access those new pages in your own time, once you’ve finished with the current page. By then, they will likely have finished loading, and will be ready to view.

When you use a single window per Web page, you have to open interesting links in new windows to achieve the same effect. In Internet Explorer, this will open a new window, which then has the “focus:” it’s brought to the front of all other windows. This stealing of focus may or may not be what you want. If it isn’t, too bad, you just have to navigate back to the original window again. You can’t change this behavior in IE; in Opera, at least, there is an ‘Open behind’ option that keeps the focus on the current page. In a tabbed system, you’re able to tell the browser whether or not to open new tabs in the background, and when you want them to steal the focus. We’ll see how to do both later.

Figure 2.5. Exposé pollution on Mac OS X.

I’ve found opening links in background tabs to be the most productive and efficient method of Web browsing. There is a near-perfect match between the basic concepts of Web browsing, and of opening interesting links in background tabs. Think about it: Web pages are built on hypertext, which means that there are always hyperlinks to other Web pages. Some links may interest you; most probably won’t. You’ll want to visit those links you do care about, so you click on them. But, wait! We’re talking about “links,” not “a link.” Usually, more than a single link will catch your attention (especially when using Google or one of the other search engines). You’ll want to visit all those interesting links, and it’s a natural process to open those links as you read the current page, so that you aren’t distracted from the current task, and visit them when you’re done. Tabbed browsing allows you to do that. IE doesn’t, because it steals focus when you open links in a new window.

The Verdict

Needless to say, tabbed browsing makes a very strong case for itself. I loved tabbed browsing the first time I tried it (in the Mozilla Application Suite). To me, it feels like the way the Web was meant to be browsed!

There is more to tabbed browsing than tabs alone, as we’ll see as we review the other features of Firefox. Firefox is built around the tabbed browsing paradigm, and, throughout this discussion, we’ll explore instances of how this integration can be used to further improve your browsing experience.

Using Tabs

By now, you’re probably convinced of the superiority of tabbed browsing – or are, at least, willing to give it a try! In this section, we’ll see how to use tabbed browsing in Firefox.

Opening, Closing and Changing Tabs

Opening a new tab is easy; it can be done in many ways.

The simplest way to open a new tab is the middle-click. Middle-clicking (or scroll wheel-clicking) on a link creates a new tab and loads the linked page into it. This is also the most efficient way to open links, so it’s worthwhile to learn to middle-click if you aren’t used to doing so. Most people aren’t even aware that scroll wheels are clickable, but you can simply click the wheel as if it were a button, as the wheel has both button and scrolling functions. If you have a three-button mouse, just click away. If you have a two-button mouse with a scroll wheel, middle-clicking can be a bit disconcerting at first. On Mac OS X, use command-left-click instead. If you like middle-clicking, you can make this a standard on the Macintosh by reassigning command-click to the mouse wheel (middle button) via the Mac OS X mouse driver.

Note that if you miss the link with the mouse pointer when middle-clicking, Firefox goes into “free scroll” mode, which is probably not what you’re after. If that happens, click again while the mouse pointer is still away from any links, and you’ll be back to normal.

Here are a few other ways to open tabs:

- Ctrl-T opens a new, empty tab.

- Right-click (or context click on the Mac) a link, and select Open Link in a New Tab from the resulting context menu.

- Hold Ctrl down while clicking a link.

- Type a URL into the location bar, then hit Alt-Enter. This loads the URL in a new foreground tab.

- Press trl-Enter when a link is selected (for example, after you’ve run a page search for it and the link is highlighted).

- Drag a URL (from a Web page or an external application) and drop it onto the tab bar.

Closing tabs is also easy and flexible: simply middle-click on a tab’s description (the bit that sticks up above the tab content). You can also use Ctrl-W to close the current tab, or you can right-click on the tab and select Close Tab. Choose whichever groove suits you. Finally, you can click on the Close Tab icon, which appears as an “X” on the right-hand end of the tab bar, and “Poof!” – no more tab. Figure 2.6 shows the Close Tab icon as it appears on the tab bar.

Figure 2.6. The Close Tab icon adjacent to the tab bar.

![]()

Once you’ve got your tabs set up, switching focus between them is easily done: just click on the required tab. Less obvious ways to switch tabs are to use Ctrl-Tab to switch focus to the next tab (to the right of the current tab), and Ctrl-Shift-Tab to access the previous tab (to the left of the current tab). This is very useful if you’ve got your hands on the keyboard most of the time.

Tab-Related Preferences

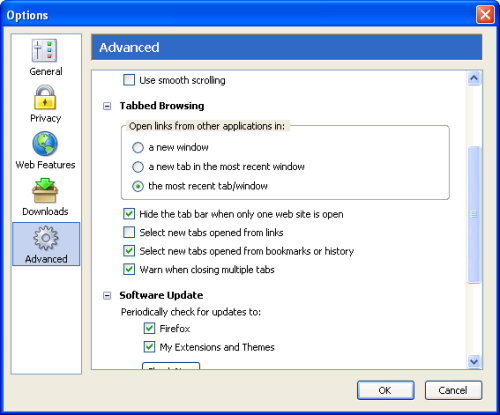

Let’s take a look at the available user preferences that are related to tabs and tabbed browsing. Start Firefox and choose Tools > Options (Windows), Firefox > Options (Macintosh) or Edit > Preferences (Linux) from the menu bar, then select the Advanced panel. You should see a dialog box that’s something like the one shown in Figure 2.7.

Figure 2.7. Tabbed browsing preferences in Firefox 1.0.

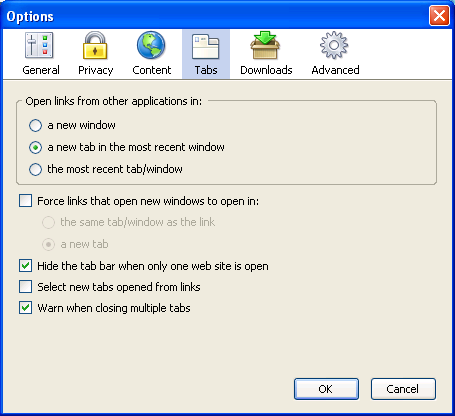

Note that the options panel has been redesigned slightly for Firefox 1.1 and beyond: there, you must click a tab rather than an icon to see this information. Figure 2.8 shows the shape of things to come.

Figure 2.8. Tabbed browsing preferences in Firefox 1.1 and beyond.

You can see that, although there’s a little reorganization, the options are much the same in both versions. Here’s what each preference does:

- Open links from other applications in:

If you click on a link displayed in an another program, such as Microsoft Word or Adobe Acrobat Reader, this preference dictates how that link will be displayed by Firefox. I prefer to have links from other applications open in a new tab in the most recent window, because I usually use a single window, and I don’t want to lose the Web page on my most recent tab. Of course, links will only load in Firefox if Firefox is set as your default browser. - Force links that open new windows to open in:

This is a newish feature that can be used to tame popup windows: check the box to turn it on. Instead of popups launching in a separate, new window, or being blocked by the popup blocker (discussed later), this option lets that new content be created inside an existing tab or an existing window. This option is available only in Firefox versions 1.1 and later. - Hide the tab bar when only one Website is open

If checked, this hides the tab bar when only one Web page is open. Personally, I have this unchecked (it’s checked by default), because it’s disconcerting to have the tab bar disappear and re-appear. This option was made the default as a deliberate design decision to enable users who don’t use tabbed browsing to enjoy more screen real estate. Users of tabbed browsing, however, will probably prefer to have this option unchecked. - Select new tabs opened from links

This is the preference I was talking about earlier, which allows you to choose whether new tabs open in the background, or steal focus from the current page. Checking this option will cause links opened in new tabs to steal focus. I recommend that you leave this unchecked to gain the productivity benefits I mentioned earlier.Note: Those who have the Select new tabs opened from links preference set one way or the other can reverse their setting temporarily with the Shift key modifier. For example, if you’ve set Firefox up so that new tabs opened from links load in the background, but you want a particular link to open in the foreground, just hold on to the Shift key when clicking the link (i.e. Shift-middle-click, or Ctrl-Shift-left-click).

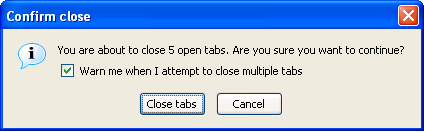

- Warn when closing multiple tabs

This option will display a warning dialog if you take an action to close more than one tab simultaneously, as will occur if you try to close a window in which multiple tabs are open. This is a useful warning that can prevent you from accidentally closing a window full of tabs, but it could be annoying if you mean to close that window. Figure 2.9 shows this warning.

Figure 2.9. Warning dialog shown when closing multiple tabs simultaneously.

As you can see, you don’t have to change any of the options if you are a “normal” user: Firefox is built so that sensible configuration choices are available from the start.

A Single Homepage: So 1999!

Another good thing about tabbed browsing is that tabbed browsers are no longer stuck with a single homepage. If you’re like most other Web surfers, you probably have more than one favorite Web page: pages that you absolutely must visit the first time you launch your Web browser. I, for example, have a total of eight URLs that I want to check at the start of every Web surfing session.

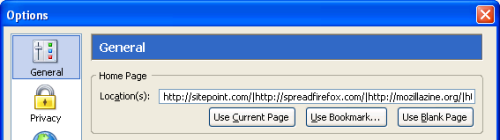

What’s a user of a Single Document Interface (SDI)Web browser – Internet Explorer, for example – to do? A Single Document Interface (SDI) is, simply put, a way to organize applications into individual windows, one for each application (or each instance of an application). If you’ve used Internet Explorer, you already know what an SDI is. Well, they’d better start looking through their bookmarks! Those lucky users of tabbed browsers, on the other hand, can set multiple homepages and load all of their favorite pages at once. Figure 2.10 illustrates the format required for setting multiple homepages via the Options dialog box.

Figure 2.10. Specifying a tabbed set of homepages.

Note the vertical bar (|) that separates each URL: one URL is shown per tab. You simply load the preferred Web pages into tabs, and mark the set as your homepage. For example, if you want https://www.sitepoint.com/ and http://www.spreadfirefox.com/ to be your homepages, load them up in Firefox, go to Tools > Options > General (or Firefox > Preferences > General on Mac OS X, or Edit > Preferences > General on Linux), then click the Use Current Pages button.

Alternatively, you can hand-enter the URLs you want to set as your homepages in the Location(s) text box, separating each using the pipe character (|) as shown above. For example, if you want sitepoint.com and Spreadfirefox.com to be your homepages, enter https://www.sitepoint.com/|http://spreadfirefox.com/ into the Location(s) textbox. The pipe character key is located near the Backspace key on most PC keyboards, and is represented by two vertical dashes placed on atop the other.

A third approach is to click on the Use Bookmark… button, and then select the bookmark folder that contains the bookmarks you want to use as your homepages. We’ll cover bookmarks in more detail later.

Setting more than a single homepage does have a disadvantage, though. If all you want to do is a quick Web search, Firefox startup is too clever (or perhaps too dumb), and insists upon loading your entire set of homepages instead. This does slow things down a bit, especially on a dial-up connection, because loading eight Web pages is almost certainly slower than loading just one. You can always press Ctrl-T to get a new tab and turn eight into nine, if you’re feeling impatient. You can then type your desired URL into the ninth tab and have it load at (hopefully) more than one-ninth of its normal rate.

Despite the performance implications, it’s hard to deny the convenience of loading up multiple Web pages at once, and it’s even harder not to feel sorry for those poor Internet Explorer users still facing dilemmas like, “Do I want Yahoo! email as my homepage, or should I set it to sitepoint.com instead?” With Firefox, you can avoid such decisions. Just set all your favorite Web pages as your homepage and be done with it!

Back, Forward and Home Buttons

Now, Firefox is a tabbed browsing Web browser, right? Of course it is. So it would make sense if Firefox could open the previous page in a new tab if you middle-click on the Back button, right? In fact, this is exactly how Firefox behaves.

You can middle-click (command-left-click on Mac OS X) on all of the Back, Forward, and Home buttons in the toolbar to open the corresponding link(s) in a new tab (or tabs). If your homepage is a set of four pages in separate tabs, middle-clicking on the Home button will add four tabs to your current tab set. Figure 2.11 reminds us of what these major buttons look like. There’s no special tab action for the Reload or Stop buttons.

Figure 2.11. Firefox’s toolbar icons.

![]()

The provision of tab support within the main browser buttons clearly demonstrates that tabbed browsing is part and parcel of Firefox’s design. It’s neither an afterthought nor a bolted-on feature.

Search and Search Tools

Search: you can’t escape it as a fundamental Web surfing activity. Well, perhaps you can if you have the uncanny ability to guess URLs that give you the exact Web page you wanted. A good dab of clairvoyance is probably necessary as well! “Hmm… Let’s see. Are there any good Firefox ebooks online? I shall use my Powers of Uncanny Deduction to find out…” (Supernatural pause.) “Ah, I’ll go to http://firefox-book.com/.”

Does that even sound remotely possible? Well, if there was a Website at http://firefox-book.com/ (there isn’t), it would probably have something to do with a book on Firefox. Relying on your powers of deduction is, in the end, unlikely to produce results, and besides, Uncanny Deduction is tremendously exhausting!

This rigmarole underscores the reality that Search is an integral part of using the World Wide Web. You can’t find the information you want using hit-and-miss techniques. Instead, we use search tools that offer systematic solutions: search engines, directories, and similar online services.

Examples of search are everywhere. Are you looking for the scoop on your favorite band? Perhaps you’re trying to learn Java programming? Google is your best bet. Are you reading up on the latest in flux capacitors and time travel for your thesis? Run a search over at ScienceDirect or arXiv.org. Looking for a good computer book, self-improvement manual, or Dragonlance novel? I’m a Dragonlance fan, in case you’re wondering. I’m not into self-improvement books, though. (It’s more fun to write your own D&D campaign settings – Ed.). Amazon.com has a nice search feature that yields customer reviews and recommendations.

If search is an integral part of the Web, it follows that it should also be an integral part of your Web browser. Firefox promises unobtrusive and integrated search functionality. The Firefox developers know what you want, and they give it to you. I wish all software projects did that!

Here, we take a detailed look at Firefox’s search-related features and see how you can best employ them to make things easy for yourself.

There’s More than One Way to Find it!

That’s right: There Is More Than One Way To Find It (TIMTOWTFI). Search is an integrated feature in Firefox, but it’s integrated in several ways. There are many separate search features and several different starting points from which you can perform a search. Each method of searching is convenient for its particular situation.

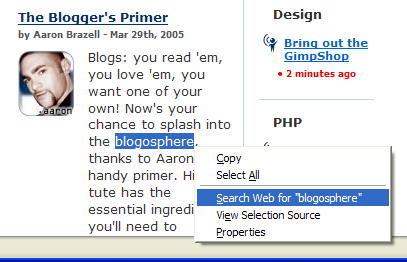

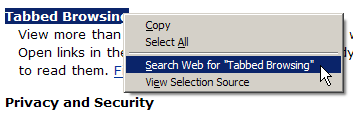

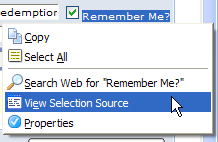

For example, you can search for the meaning of a word or phrase (say, “blogosphere”) on a Web page by highlighting it, then context-clicking and selecting the context menu entry Search Web for “blogosphere.” Figure 2.12 shows this technique at work.

Figure 2.12. Context Web searching for highlighted text.

Alternately, you can surf to the search engine’s homepage and type your search terms into the form (not that this is a Firefox feature, but it is a way to perform a search). Or you can… but let’s put an end to these trivial examples and dive straight into discussing the more effective and efficient ways that you can search using Firefox.

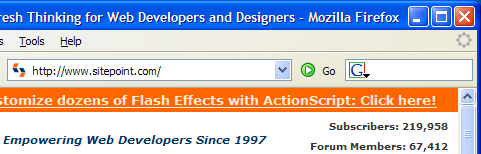

The Search Bar: Drunk on Search!

When you first launched Firefox, you probably noticed that there were two textboxes into which you could type text. One of these is the location bar, into which you can type URLs; the other has a funny looking “G” next to it. Figure 2.13 shows this corner of the browser.

Figure 2.13. Search bar on the right, location bar on the left.

The “G” is actually an icon for the Google search engine, and this textbox is called the “search bar.” If you type in a search phrase, and hit Enter, Firefox will take you to the Google search results page for that phrase. Go ahead and try it out for yourself: it’s a very convenient arrangement. No longer do you have to type in http://www.google.com/, wait for it to load, and then search using the standard form. The search bar saves a good three seconds each time you do a search – possibly more if you’re on dial-up. Since the average Web surfer performs 12 searches per hour, that’s a good 36 seconds saved for every hour spent online, or 14.4 minutes per day, or 3.65 days per year! This figure was derived through a complex process called guessing! Try doing a search on Google for “36 seconds per hour in days per year.” Google’s calculator kicks in and does the conversion for you! I knew Google’s calculator function was really smart, but this smart?! Imagine what you could do with those 3.65 days. You could take a three-day vacation and still have 0.65 days left in which to do nothing. When the Firefox folks say that Firefox helps make your online experience more productive, they aren’t just boosting the marketing hype: the productivity increases are real.

Using the Search Bar like a Pro

The search bar is easy to use, but you can do a lot more with it than merely search Google. Learn these other tricks before you embarrass yourself in front of your Firefox evangelist friends!

To start with, hitting Enter loads the search results page in the current tab. At times, it may be more convenient to load in a new tab. For cases like this, hit Alt-Enter instead of just Enter.

The shortcut keys that place the input cursor in the search bar are Ctrl-K and Ctrl-E – you can use either. If, like me, you don’t like to take your hands off the keyboard, those shortcuts are very useful. The way I search is to hit Ctrl-E, type in my query, and then hit Alt-Enter to specify a new tab.

You can also search using drag and drop. Simply select a piece of text (from any drag and drop-capable program, not just Firefox), and drag it into the Firefox search bar. And, if you’re thinking of dragging and dropping text from a Firefox Web page specifically, there is an Even Better Way! Let me keep you in suspense for now: we’ll come back to this shortly.

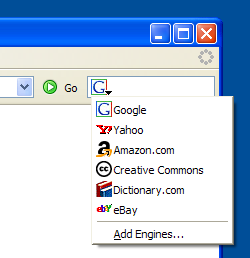

Adding More Search Engines

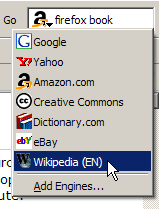

You aren’t restricted to searching on Google, even if it is the best search engine around and complemented by totally cool software. You can easily add other search engines, like AltaVista, AllTheWeb, and even the new kid on the block, Clusty. To do so, click on the G icon. You should see a drop-down like the one shown in Figure 2.14, which lists the search plugins installed by default in the Firefox product.

To search with a different search engine – say, Amazon.com – simply select that item from the drop-down. The icon to the left of the search box will change from the G icon to its Amazon equivalent. Now, any searches you perform through the search bar will be run on Amazon.com (try searching for “Firefox”).

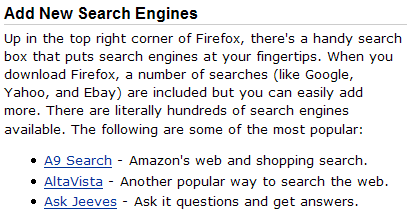

Naturally, everyone has his or her own specific needs and favorite search engines. You’ll probably be wondering how to add a new option to the search bar, and you might have guessed that you simply click the Add Engines item in the drop-down to do so. Choosing that item takes you to Firefox Central, where you can add other search plugins. Figure 2.15 shows a slice of that page.

Figure 2.14. Adding and changing search engines.

Figure 2.15. Adding new search engines at Firefox Central.

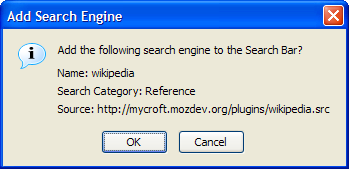

Figure 2.16. Adding the Wikipedia search plugin.

To add a particular search engine, just click on the appropriate link. Let’s add the search plugin for Wikipedia (a very useful and comprehensive online encyclopedia). You should see the confirmation dialog shown in Figure 2.16 after you click on the Wikipedia search plugin link.

Click OK, and you’re done! You can now see Wikipedia in the search bar drop-down. Simply select it to search Wikipedia, as shown in Figure 2.17.

Figure 2.17. Successful installation of the Wikipedia search option.

If you want to add a search engine that isn’t on the provided list, go to the Mycroft project Website, which offers a collection of search plugins for many sites. Search for the plugin you want, or browse the search plugins categories. Over a thousand search plugins are listed here, so there’s definitely something for everyone.

Removing a search engine from the search bar is a little bit of a hassle. First, use the desktop file manager (Explorer or Finder) to locate the searchplugins directory inside the Firefox installation directory. It’s at C:Program FilesMozilla Firefoxsearchplugins on Windows systems. There, two files are stored for each search plugin. One is a .src file, the other is a graphic, usually either a .png or .gif file. Delete the pair of files whose names match the search option that you no longer want. For example, if I wanted to remove the Yahoo! search plugin, I would simply delete yahoo.src and yahoo.gif, then restart Firefox. An interface for removing unwanted search engines is planned for inclusion in a future release of Firefox. The related bug note is available online.

Next, we’ll take a look at a clever and convenient way of searching.

Smart Keywords

Smart Keywords are a great way to perform search queries from the location bar. With smart keywords, you can type dict extemporaneous into the location bar, hit Enter, and be taken to the Dictionary.com definition of “extemporaneous.” The hard way to do this is to go to Dictionary.com, wait for it to load, click on its search box and enter extemporaneous. Bah! That takes too many steps.

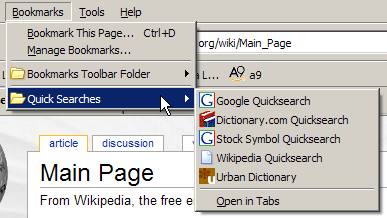

Firefox comes with several Smart Keywords automatically installed. You can find them in the Quick Searches folder in your bookmarks, as illustrated in Figure 2.18. You don’t have to use this menu at all – it’s just an easy way to see which Smart Keywords are installed.

Figure 2.18. Firefox’s pre-defined Smart Keywords offering.

The predefined Smart Keywords are:

- Dictionary.com

Typedict wordto lookup the definition of a word. - Google

Typegoogle search keyword(s)to perform a normal Google search. - Stock Symbol

Typequote symbolto look up stock quotes for a stock symbol. This content is sourced from Yahoo! Finance by Google. - Wikipedia

Typewp anythingto access the Wikipedia entry on just about anything (Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia). - Urban Dictionary

Typeslang slang wordto look up the meaning of urban slang words, and keep up with the times!

I’m sure you’re wondering how Smart Keywords are created. After all, it would be nice to construct additional keywords for searches that Firefox has not already provided for you. There are two ways to create a Smart Keyword: the easy way, and the hard way. The easy way is preferred, but when it occasionally fails, you’ll have to fall back on the hard way. Let’s look at both, starting with the easy way.

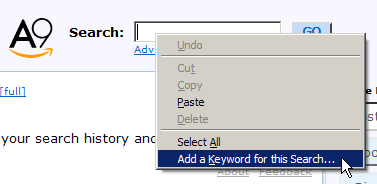

Let’s add a Smart Keyword for A9, Amazon’s relatively new search engine. First display A9’s homepage. Right-click in the search box, and you should see the context menu item Add a Keyword for this Search…, as shown in Figure 2.19.

Figure 2.19. Adding a Smart Keyword from a search field.

The last item on the menu looks like the one we’re after, and indeed it is. When you pick that item, an Add Bookmark dialog will appear, prompting you to fill in the name of the bookmark as well as the keyword. Let’s name it A9 keyword and use a9 for the special keyword. Save the result in a bookmark folder of your choice – I recommend you save it in the Quick Searches folder with all the other predefined Smart Keywords.

When you’re done, you can try it out straight away. Enter a9 firefox, and you’ll be taken to the A9 search results for the “firefox” search term that you entered. Great! We’re making progress.

Now, let’s try doing this same task the hard way. We’re not doing this just so we can say we’ve done it to impress fellow guests at dinner parties. We’re doing it because the easy way doesn’t work.

For example, go to the Yahoo! search engine, and try to add a Smart Keyword the easy way. Nothing happens: no Add Bookmark dialog appears – at least, not as this book goes to print. (Technically, this is because the Yahoo! Search text field is not specified with id=”search”).

Perhaps Yahoo! will fix this someday. Perhaps it will already have been fixed by the time this book lands in your hands: such is the nature of the Internet. Fixed or not, it’s clear that many Websites do not support the easy addition of Smart Keywords.

To add a Smart Keyword the hard way, you must first study Web addresses a little. Type a query into the search box, hit Enter, and look at the URL that’s generated. We need to pull that URL apart for our own purposes. If we use the Yahoo! Search search engine to search for “firefox,” the resulting search URL looks like this: http://search.yahoo.com/search?ei=UTF-8&fr=sfp&p=firefox. Those who are familiar with URL query strings, and understand how certain search engines work, will recognize that only http://search.yahoo.com/search?p=firefox is necessary to perform the search. The rest is extra information for Yahoo!, like the character encoding for your search query and where you conducted the search.

Replace the search query (“firefox”) in that URL with %s to create a URL that’s suitable for a Smart Bookmark. A Smart Bookmark is a special bookmark that is used to define a Smart Keyword. Firefox recognizes “%s” as a placeholder for your keyword, and replaces it with your typed information whenever you perform a Smart Keyword search. If you enter two or more words, possibly separated by spaces, Firefox treats them all as a single keyword string. So you can only use “%s” once.

To create the Smart Bookmark, we bookmark the search page (the ordinary search page for the search engine in question), then modify the new bookmark. We change the bookmark’s name to something better, like “Yahoo! QuickSearch,” and tweak the bookmark so that it acts in a Smart Keyword-like manner. We then save the bookmark in the QuickSearch bookmark folder.

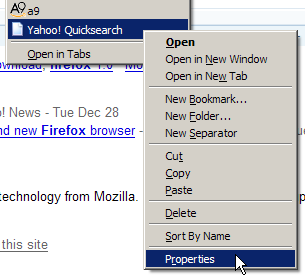

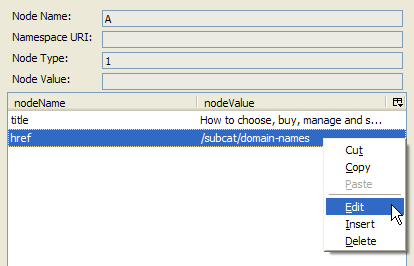

To do all this, find the new bookmark in the Bookmarks menu, select it, right-click, and select Properties. Figure 2.20 shows the menu that holds the Properties item.

Figure 2.20. Displaying a plain bookmark’s properties.

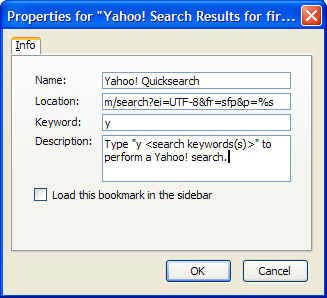

Choosing Properties should bring up the bookmark properties dialog, in which we can make all the required edits. Update the name, replacing “firefox” with the special %s placeholder, and provide a keyword (I chose “y” for “yahoo”). You can also add a description if you wish. Figure 2.21 shows these changes.

Finally, click OK, and there you have it: a Smart Keyword for Yahoo! Search. Try it out for kicks.

Now that you’re armed with enough knowledge to create Smart Keywords the hard way, you can use it to do some innovative and interesting stuff. Let’s create a currency conversion Smart Keyword that converts from European Euros to US Dollars. Using the service at XE.com, let’s try to do this the hard way.

It turns out that this task is even more challenging than usual. Web developers will understand me when I say that the xe.com currency converter normally uses HTTP POST for form submission, instead of HTTP GET, so there isn’t a URL that we can exploit: one into which we can insert the “%s” placeholder we used before. POST (or rather, HTTP POST) is a method of passing data to a Web page (or rather, a Web server). The Smart Keyword system can only use URLs based on GET requests. Non-developers probably won’t understand this technicality, nor should they have to. The upshot is that we need to find a GET request that we can use as the basis of our Smart Keyword.

Figure 2.21. Specifying the Yahoo! Quicksearch Smart Bookmark properties.

To do so, we have to dig into the HTML source of the Web page that performs the search (from the menu, choose View > Page Source, then start tearing your hair out!). With a little digging into the HTML source of the http://www.xe.com Web page, we can deduce that a useful Smart Keyword URL would be: http://www.xe.com/ucc/convert.cgi?Amount=%s&From=EUR&To=USD

We bookmark that URL, and edit the bookmark properties, remembering to give it a keyword: “e2u” is a good choice. To test out the new keyword – for example, to find out how much one million Euros is worth in USD – type e2u 1000000 in the location bar.

If you know how to sift through HTML source, life is great; if you don’t, life isn’t so terrible. A little help from someone else is all you need. Here are some other Smart Keywords that you might consider.

- Google I’m Feeling Lucky

- Altavista

- Amazon

- Google News

- Google Groups

- eBay

- Feedster recent blog posts

- The Internet Movie Database

- Thesaurus.com

- CiteSeer (Computer and information science publications database)

The basic premise behind the Smart Keyword feature is very simple: it simply replaces the “%s” placeholder with the keyword that you type in. Armed with this knowledge, you can make a Smart Keyword for just about any Web service that has a variable component in its URL.

Right-Click Text Searching

I started this section by saying that TIMTOWTFI (There Is More Than One Way To Find It). Then, we searched for the text “blogosphere.” That technique is called “text search,” and it’s something that bears a little further exploration.

To perform a text search, you must master two mouse gestures: highlight, and context select. Highlighting text is easy – for simple operations, at least. To do so, click before the required piece of text, then, holding the left mouse button down, drag the mouse over the text to create the highlight. Release the mouse button to finish the highlight. When you do the context-selection (right-clicking on the highlighted content), you’ll see a Search Web for “whatever you selected” item appear in the context menu, as shown in Figure 2.22.

Figure 2.22. Convenient search from the context menu.

If you left-click on this menu item (I dare you to!), Firefox will perform a search for the selected text on Google in a new background tab. Yes: on Google, again!

Text search isn’t restricted to text, either. If you highlight an image on the page (by clicking just outside the left edge of the image, then dragging across it), the context menu will provide a search based on any alt (descriptive) text that’s specified with the image. Alas, if the image is provided as part of a style, you can’t do this yet; the image must be a proper part of the page.

You can also perform a highlighted search for text that appears in a link. Highlighting text in a link is quite tricky, though: you might accidentally start a download or open a tab if you try to drag-highlight across such text. Instead, start by highlighting the text with the Find Links As You Type feature (discussed next as part of the section called “FastFind: Find As You Type”). Once the text is highlighted, bring up the context menu by right-clicking on it as you would for any highlighted text.

As yet, you can’t perform a text search on text inside a textbox or a text input field, but that feature may come in future.

What if you don’t want to use Google as the default search engine? A bit of geek-speak is required to change that. You might like to read Chapter 6, Tips, Tricks, and Hacks before experimenting, though.

Type about:config into your Firefox address bar, hit Enter and look for the browser.search.defaulturl preference in the displayed set of preferences. Its value should be set to: http://www.google.com/search?lr=&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&q=. Replace this string by right-clicking on the preference. Use http://search.yahoo.com/search?p= for a Yahoo! search, or the equivalent string for another engine. Note that “%s” is not required in this case.

FastFind: Find As You Type

Other than searching for a Web page, you will often find yourself searching within a Web page. This is especially so for Web pages that contain lots of (largely irrelevant) content, for long listings, and when you’re looking for a specific piece of information.

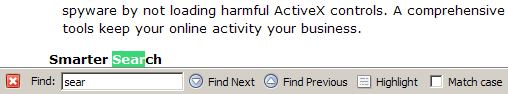

Firefox has an easy to use über-feature called FastFind. This is the official marketing buzzword; it’s also known among veteran Firefox users as Find As You Type (FAYT), or Type-Ahead Find. Find As You Type does exactly what it says: it finds text as you type. How does it work? Just hit / (forward-slash) or Ctrl-F, then start typing the word (or words) you’re looking for. Firefox will find and highlight the first instance of the word(s) that matches what you’ve typed, from the second you start typing. The easiest way to see what I mean is to try this out for yourself. Go to the Mozilla site and type /firefox as soon as the page has finished loading.

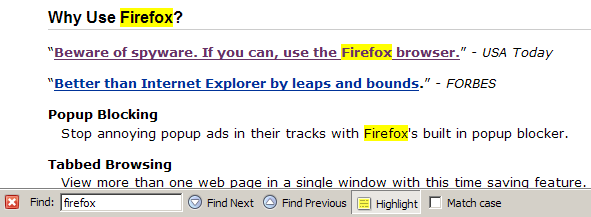

You can also use F3 or Ctrl-G to find the next match on the page, and Ctrl-Shift-G to find the previous match. So there’s no need to take your hands off the keyboard, and no need to deal with a pesky Find dialog window that gets in the way! Instead, you get an unobtrusive Find toolbar at the bottom of the page, as shown in Figure 2.23.

Figure 2.23. The Find toolbar.

This is one of my favorite Firefox features. When I occasionally use Internet Explorer, I often lapse into hitting / and typing text in an attempt to search for stuff. Alas, this feature doesn’t work in IE…

If you’re daunted by having to remember keyboard shortcuts, have no fear: the Find toolbar is here (so much for poetry). Whenever you start a find, the toolbar springs into existence at the bottom of the page. You can use the buttons on the Find toolbar to find the next or previous matches. I recommend you get used to the keyboard shortcuts though, because they really speed up the searching process.

Perhaps you noticed the Highlight button in the Find toolbar. You can use this to highlight all text that matches your search word(s). The keyboard shortcut for this is Ctrl-Enter. Figure 2.24 shows what this looks like.

Figure 2.24. Highlighting “Firefox” through the Find toolbar.

This kind of highlighting uses yellow to mimic the action of a felt pen highlighter, and doesn’t change your current selection. There’s also a checkbox that you can check should you want to match case (i.e. typing FiReFoX will match “FiReFoX” but not “Firefox” or “firefox”).

Tip

There are probably times when you want to search only within the text of links, ignoring all the other text on the page. A good example is my endless scanning for the “download” link on a Web page. To start searching only within links, hit ‘ (single apostrophe), instead of the usual / (forward-slash) or Ctrl-F, then start typing as you normally would. Only link text that matches your search term is highlighted. When you come to a link that you want, you can use Enter to load it in the current tab, or CtrlEnter to load it into a new tab.

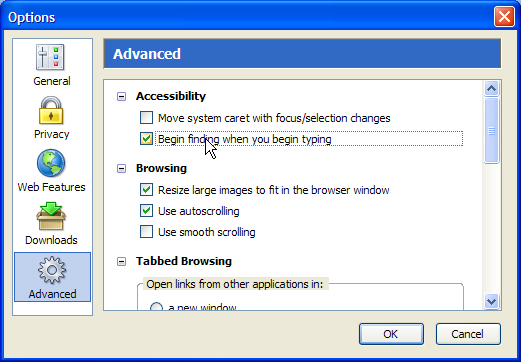

A final variation that improves the efficiency of your searching is to enable the preference Begin finding when you begin typing, which can be found under Tools > Options > Advanced >Accessibility (Firefox >Preferences on Mac OS X, Edit >Preferences on Linux). That option’s shown in Figure 2.25.

When this preference is enabled, you no longer have to hit / or Ctrl-F to start a search: just start typing your search phrase! This used to be the default behavior prior to Firefox 1.0, and is a well-loved feature among power users, yours truly included.

Figure 2.25. Begin finding when you begin typing.

Search is what you do with a browser when you want to find something. But, what do you do when you’re presented with information that you’d rather not know? We take a look at this issue next.

Non-invasive Browsing

Firefox has built-in features that make your online browsing experience as smooth and uninterrupted as possible. Lots of features exist to remove the annoyances we tend to suffer when using IE. Popup and pop-under ads, spoofed status bar text that hides URLs, animated status bar text, flashing “Click me!” banner advertisements, windows that resize themselves to be either incredibly small or incredibly large: all these are annoyances. I have not seen any of them since I started using Firefox.

Annoyance elimination is the process of silently removing all these irritants. Annoyance elimination is one thing at which Firefox excels, so let’s see how you can configure Firefox to create the uninterrupted browsing experience that you deserve.

Popup Blocking

In the past, we lived with popup and pop-under windows that contained advertisements as if they were an unavoidable part of life. Fortunately, someone conceived of popup blocking software, which provided some relief. Eventually, software developers started building popup-blocking capabilities into their browsers; Firefox is one such browser. Popup blocking has become such an important feature of Web browsers that you’d now be hard-pressed to find one without it. Firefox, Safari, the Mozilla Application Suite, and even Internet Explorer on Windows XP (provided Service Pack 2 is installed) offer integrated popup-blocking features.

If you visit sites that use popups as a necessary element of the site’s functionality (a banking site, for example), or you simply have some strange popup ad fetish, you can turn off Firefox’s popup blocker, either globally, or on an individual site basis. We’ll see how to tune the Firefox popup blocker to suit your requirements as we move through this discussion.

Note

This is not the place to discuss the “ethics” of popup blocking and online advertising, so throughout this discussion I’ll assume you’ll want to block popups. What has popup blocking got to do with ethics? Well, people argue that since online advertising is what funds many free (and non-free) Websites, popup blocking is like stealing from these sites, since they don’t get revenue from your viewing of their content. To debate these issues is beyond the scope of this book.

Avoiding Popups

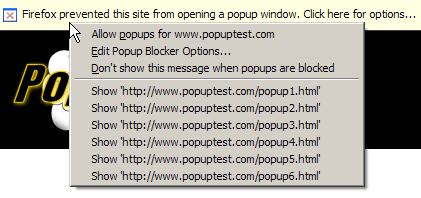

Firefox is configured out-of-the-box to block popup windows, so you don’t need to do anything to get this working. You can test out the popup blocker by going to a Website that uses popups. I suggest searching for “popup test” and visiting one of the popular testing sites. Whenever Firefox encounters a Website-initiated popup, as opposed to a user-initiated popup (more on that shortly), it will block that popup and display a notice that it has done so. You can see an example of the notice in Figure 2.26: the strip across the top appears by default; the displayed menu appears if you click on that strip.

Figure 2.26. Firefox’s popup blocker generating a notice and blocked popup menu.

In this example, Firefox has dutifully blocked a popup from PopupTest.com. If you want, you can choose from the context menu the option to permanently allow popups from that site; additionally, you may (just once) choose to load the blocked popups.

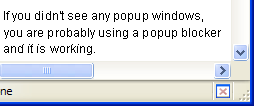

When popups are blocked, you will also see an icon at the bottom right corner of your Firefox window: this will always be visible, even after you select Don’t show this message when popups are blocked. In Figure 2.27 the icon appears to the left of the window resize grip (the small triangle of dots in the bottom-right corner).

Figure 2.27. The blocked popup icon.

To view any blocked popup, click on the information bar and select the appropriate Show ‘http://www.example.com/popup.html‘ option. The blocked popup will burst into existence for one time only. This is useful if you want to be sure you aren’t missing anything (like a good deal on Viagra).

You can also tell Firefox to allow the Website to open popups from this point forward for a particular site. This is best used when you trust the Website and don’t mind seeing its popup windows – perhaps it’s a work-related Website whose popups you should see. Whatever the reason, you can view popups for a given site by selecting Allow popups for www.example.com from the information bar.

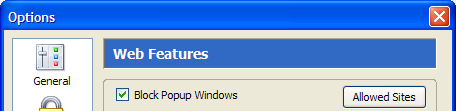

Don’t be afraid to allow popups: you can just as easily disable popups again. To do so, access the Popup Blocker Options. Under Tools > Options > Web Features, you will see a Block Popup Windows checkbox, with an Allowed Sites button beside it. Figure 2.28 shows this feature.

Figure 2.28. Popup blocker options.

Click on the Allowed Sites button to bring up the list of sites that are allowed to open popup windows in your browser. An example setup is shown in Figure 2.29.

Figure 2.29. The Allowed Sites dialog.

This dialog holds a simple whitelist of sites whose popups are allowed to appear in your browser. You can add Websites to the list by typing their URLs into the Address of web site field in the dialog, but that’s the hard way to do it. It’s much easier to allow popups from the information bar, as we did before. Removing a site is as simple as selecting it in the list (left-click), then clicking the Remove Site button.

User-Initiated Popups

A small note about popup blocking: Firefox doesn’t block user-initiated popups. Such popups occur if you click on a link that spawns a popup. If you do this, the popup isn’t blocked, because you asked for it. This is logical behavior: if I click on the link, I probably want it to do what it’s supposed to do. See the Tabbed Browsing discussion in Chapter 3, Revisiting Web Pages for a way to trap even these popups inside an existing window or a tab.

User-initiated popups are often implemented using JavaScript. Next, we’ll see how to control what JavaScript can and can’t do.

Disabling Annoying JavaScript

I don’t know about you, but all those pesky things that Websites do with JavaScript really annoy me. My pet-hates are popup windows that spawn more popup windows, animated status bar tickers that obscure the normal status bar text, and spoofed status bar text that tries to mislead.

I’d always wished there was a way to turn off those particular JavaScript effec ts in my browser without losing the rest of the dynamic JavaScript functionality offered by the Websites in question. Preventing a Website from spoofing the status bar text is good. Preventing a dynamic form from using its JavaScript scripts to calculate whether I am “the life of the party” or the “uninvited nerd” is not so helpful.

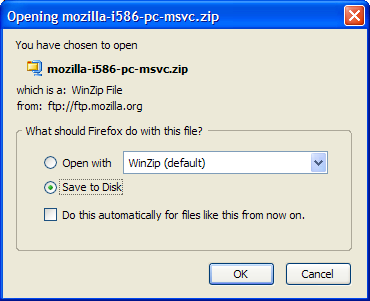

Firefox supports this distinction nicely by blocking certain JavaScript calls while allowing the rest. Exactly which JavaScript calls are blocked can be configured in the Web Features preferences pane.

JavaScript Web Features

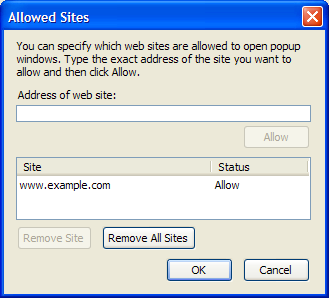

To find these JavaScript settings, look in the Web Features pane of the Options or Preferences dialog box. There is an Enable JavaScript checkbox alongside an Advanced… button on which you can click. Figure 2.30 shows this arrangement and the resulting secondary dialog box:

Figure 2.30. Advanced JavaScript options.

Don’t be afraid to play with the options here just because they’re described as “Advanced.” These are actually fairly obscure options, rather than particularly advanced options. Here’s a run-down of what each does.

Move or resize existing windows

Uncheck this to disable JavaScript that tries to resize a browser window that’s already open. Sites that do this usually want to make the window smaller. They’re often Web design sites, but can simply be sites that were created to annoy the heck out of you. This option will not prevent a popup window from choosing its own size, however. Popup windows can choose their own size provided that you’ve allowed popup windows, or the window is a user-initiated popup.

Raise or lower windows

This option is a little ambiguous at first inspection and, initially, I had some trouble figuring out what “raise” and “lower” actually meant! These options control whether JavaScript can be used to bring a window to the front (that’s “raise”) and, therefore to the top of the windows displayed on the desktop, or, conversely, to hide a window under others (that’s “lower”). A common example of the “lower” case, typically used for devious purposes, is the pop-under window, where a Website tries to open a secret window that you won’t notice. Sometimes this feature is needed, though, especially when Web-based applications need to maintain several open windows at once, or windows need to display warning messages.

Disable or replace context menus

Have you ever come across Websites that prevent you from right-clicking? No? Perhaps you remember trying to save an image that caught your fancy, only to find that you couldn’t right-click; instead, you’re told sternly that the image is copyrighted and not for download. When the Disable or replace context menus option is checked, that kind of thing may happen. Unchecking this option disables any JavaScript that tries to hide the context menu, so that the context menu is always free for you to use.

Hide the status bar

Uncheck this option to prevent Web pages from hiding the status bar at the bottom of the Firefox window. This is a highly recommended option since an absent status bar creates a security risk (see the next point).

Change status bar text

Some Websites spoof the status bar text, replacing the actual URLs of links with other URLs, or other text. Some sites have annoying animated stock ticker-like text that screams “WeLcOmE tO mY hOmEpAgE!” This is not only annoying but a security risk, because you can be fooled into clicking a link that goes to a URL that you weren’t expecting to visit. A carefully crafted piece of status bar text can also mislead you rather than annoy you. This is a so-called “phishing” scam that attempts to mimic normal browser functionality. I highly recommend you leave this option unchecked.

Change images

Unchecking this option disables features like JavaScript rollovers and dynamic menus that rely on images. It also disables some obscure form submission techniques based on image replacement.

Downloading for Dummies

Using Firefox to download files from the Internet is a pretty common activity. It helps if the browser makes this mundane stuff hassle-free. Firefox has several standard features that make downloading easier; we’ll step through these now. Later in the book we’ll see how to enhance that download support with extra features.

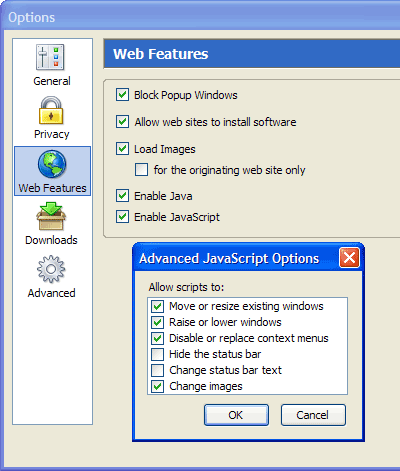

Downloading Files

When you first download a file, Firefox displays a dialog window that asks you what it should do with that file. Choosing to open the file instructs Firefox to download the file to a temporary directory and then open it with the application you selected in the drop-down. As you’d expect, saving to disk simply saves the file to your hard disk. Figure 2.31 shows this initial dialog box:

Figure 2.31. The file download dialog.

Downloads that are risky, such as executable files, cannot be opened by Firefox automatically: you can only save such files direct to disk. In such cases, the Open with option is disabled, as you can see in Figure 2.31. This restriction prevents you from accidentally running an application that you did not intend to run.

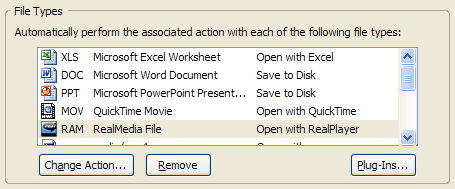

Notice also the dialog checkbox labeled Do this automatically for files like this from now on. This option instructs Firefox to remember your preference and to pre-select it the next time you download a file of the same type. You can change this behavior in the Downloads section of the Options dialog box (Tools > Options, Firefox > Preferences or Edit > Preferences, depending on your platform). Figure 2.32 shows this dialog box after a few common file types have been configured.

Figure 2.32. Configuring file type associations.

Once Firefox has recorded your initial preference, you can change the default action taken for a remembered file type. Clicking the Change Action… button will allow you to change the application with which Firefox opens files of this type, or lets you tell the browser to revert to saving them directly to disk.

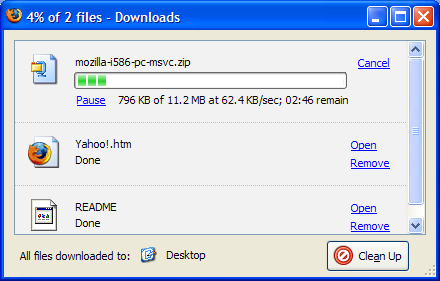

The Download Manager

Firefox comes with a Download Manager that displays all of your downloads in one place. Instead of displaying a download dialog for every single download, as Internet Explorer does, Firefox gathers your downloads together in a single location where you can track their progress without having to contend with multiple windows. Figure 2.33 shows the Download Manager.

Figure 2.33. The Download Manager in action.

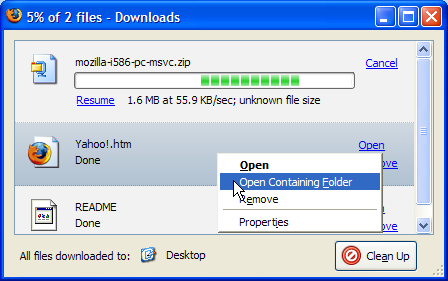

Figure 2.34. Opening a folder containing a downloaded file.

Let’s quickly discuss exactly what you can do in the Download Manager. Firstly, you’ll notice that downloads in progress can be paused or cancelled. Resuming paused downloads only works if the server supplying the file is configured that way, so don’t pause if you’re unsure of the server. Completed downloads can be opened by clicking the Open link, or double-clicking the row in which the file is listed. Completed downloads can also be removed from the Download Manager. Note that Remove doesn’t delete any files from disk: it simply removes them from the Download Manager. Another commonly needed action is to open the folder containing the downloaded file. This can be done by right-clicking the row on which the file is listed in the Download Manager, and selecting Open Containing Folder. Figure 2.34 shows that detail.

Notice that, at the base of the window, there’s also an indication of the standard download directory. This is correct provided that you haven’t configured Firefox to ask you where to save each downloaded file. In the screenshot above, the Download Manager helpfully reminds us that files are downloaded to the desktop, which is a folder or directory associated with the current operating system user account.

Finally, the Clean Up button is used to remove completed and cancelled entries from the Download Manager, which helps to keep the list of entries in the Download Manager to a sane limit. When all downloads are complete, Firefox pops up a small notification window in the bottom-right corner of the desktop, as shown in Figure 2.35.

Figure 2.35. The Downloads Complete notification.

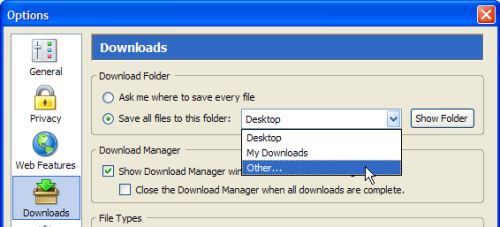

Firefox saves all downloads to the desktop by default, and does so without prompting. If you prefer to save to another location, or to have Firefox prompt you for a save location for every new download, go to Tools > Options > Downloads (on Windows) and change the settings in the Download Folder section shown in Figure 2.36.

Figure 2.36. Configuring Download Folder options.

To be prompted for a save location each time you download, make sure the Ask me where to save every file option is selected. Otherwise, if you’d like to change the automatically selected default download location, simply select Other… from the drop-down, and choose the folder you want.

If you find the Download Manager a little annoying (in which case, you’re not alone) you can disable it through the Downloads preferences (Tools > Options > Downloads on Windows) by unchecking Show Download Manager window when a download begins. If you do so, you can still call up the Download Manager from Tools > Downloads or via the Ctrl-J shortcut key. You will always be notified when all downloads are complete.

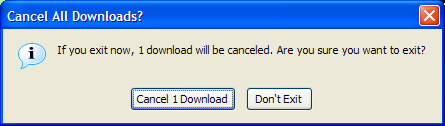

If you press Pause in the Download Manager while downloading a file, you can resume that download anytime as long as Firefox is still running. The Download Manager doesn’t support the cross-session resumption of downloads as yet. Cross-session resuming is a rather useful feature that allows you to close Firefox, or even shutdown your computer, while downloading a file. When you start up again, the download picks up where it left off. This feature is targeted to appear in Firefox 2.0: see this functionality outline for more. While we (especially those of us on dial-up) wait patiently for this killer feature, you may be comforted to know that at least Firefox protects your in-progress download with a warning if you try to exit the browser prematurely. The dialog in Figure 2.37 shows that warning, which provides you with an opportunity to reverse your hasty exit decision. If you keep going, your partially downloaded files will have to be re-downloaded from scratch.

Figure 2.37. The partial downloads cancellation warning shown on exit.

Installing Plugins

Plugins are add-on programs that allow you to view non-HTML content such as PDF files, Flash content, Java applets, and video within Firefox browser windows, or in separate windows created from Firefox windows.

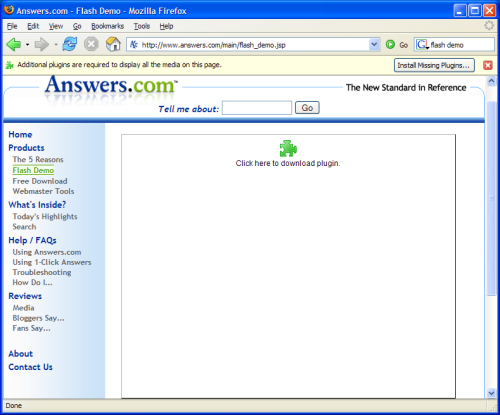

If a plugin is missing when you view a page that carries plugin content, then you’ll see a jigsaw piece in place of the content; a yellow plugin information bar will also appear at the top of the page. Figure 2.38 shows this arrangement when the Macromedia Flash plugin is missing.

To install the required plugin automatically, just click the Install Missing Plugins… button and let Firefox find the plugin for you. Follow the resulting install prompts as you normally would. At the end of that process, the current page is redisplayed with the plugin content presented by the new plugin.

Major plugins are available for Adobe Acrobat, Macromedia Flash, Java, Apple Quicktime, Realplayer, and Windows Media Player. Firefox knows how to get all of these plugins. However, if, by some chance, the plugin isn’t found by Firefox, or you want a particular version of the plugin or some other special arrangement, you can install plugins yourself. You can obtain most plugins at https://addons.update.mozilla.org/plugins/.

To install plugin software from that page, look for the link that suits your operating system, click it, and follow the instructions on the resulting page. Supporting documentation is also found at the PluginDoc project. You can refer to that more extensive site should you have any problems.

Figure 2.38. The plugin content placeholder and information bar.

Getting to your Email

Firefox has an email integration user interface (UI) feature that lets you create and read emails from your browser. It’s available on Microsoft Windows only. You can access this extra feature from the Tools menu: it even indicates to you how many unread emails you have, provided that Windows has registered a default email application. Of the two menu options supplied, choosing Read Mail will launch your default email application (probably Outlook, Outlook Express, or Thunderbird); choosing New Message… creates a new email message for you. Figure 2.39 shows these menu items.

Figure 2.39. Windows email options on the Tools menu.

If you choose to customize your toolbars (use View > Toolbars > Customize…), you can add an email button to the navigation bar. It contains a drop-down list that provides the same options for reading and creating emails. Figure 2.40 shows this button after it’s been left-clicked.

Figure 2.40. Toolbar-based email button.

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve covered the core functionality of Firefox: the basic things you need to know to work efficiently with Firefox on the Web.

We took a good look at tabbed browsing and how it compares against the old-school non-tabbed browser interface. This author’s conclusion is that tabs are a superior way to browse. Annoyance elimination is another task at which Firefox excels, and in addition to the standard features, you can also change popup blocking and disable bothersome JavaScript.

There Is More Than One Way To Find It (TIMTOWTFI) in Firefox, and by now you should be a master of search using Firefox. Smart Keywords are particularly clever, and so are you, now that you know how to create and use them! We also covered what I think is another killer feature of Firefox: FastFind, which allows you to search text within a page quickly.

On top of tabs, popups and search, we briefly covered working with non-Web content: downloading files, installing plugins, and accessing email. Firefox integrates quite well with all of those not-strictly-Web-browsing activities.

In the next chapter, we’ll continue our exploration of Firefox’s standard browsing features. We’ve already learned that Firefox is an efficient system for carrying you from the current page to the next page. In Chapter 3, Revisiting Web Pages, we’ll see that Firefox has many helpful features when the time comes to revisit a page that you’ve already visited.

Sample Secrets

Chapter 6, Tips, Tricks and Hacks

There are many subtle features hidden beneath the Firefox hood, many of which aren’t accessible from the menu system: some even require that you learn hidden keyboard incantations! In this chapter, we dive into the deep end of the pool, where such wonders lie. We’ll take a look at Firefox’s hidden preferences, and uncover the hidden mysteries of your Firefox profiles. We’ll also explore some useful tricks that do everything from speeding up the browser, to changing the way it looks and responds.

The Secret Named about:config

Firefox is designed to be immediately usable, without any configuration effort. There’s no confusing glut of preferences and options in the user interface – a problem that plagues a number of other applications and Web browsers. By design, Firefox has fewer configuration interface intricacies than do comparable tools.

While this approach is vital for everyday use and for the “everyman” user, “power” users need something more flexible. Those special users are not left in the lurch, though, because Firefox has numerous extra preferences that one can set, albeit via a somewhat unofficial method. Such hidden preferences are managed through the about:config configuration page. This is a special interface to the Firefox preference system.

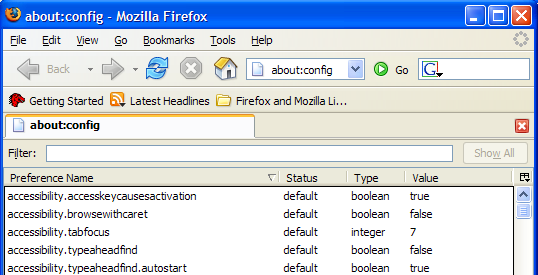

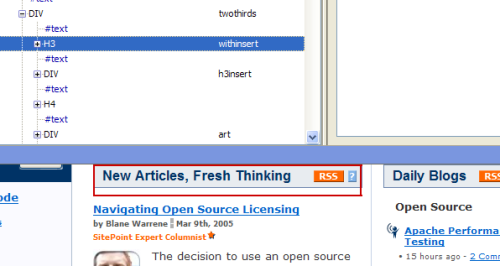

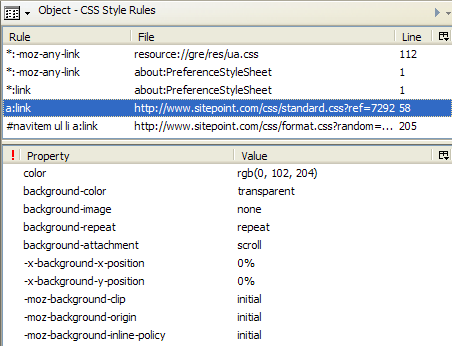

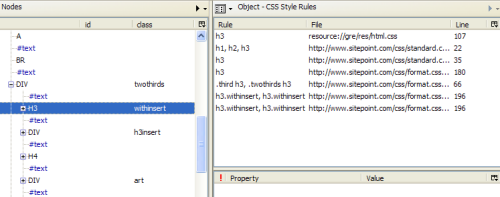

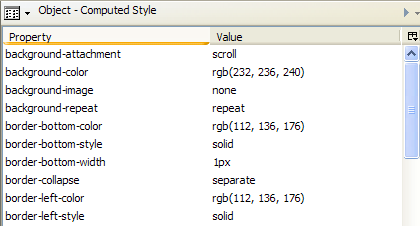

To call this interface up, type the special URL or Web address, about:config (yes, that’s correctly stated) into the location bar, and hit Enter. You should see something like Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1. Introducing the about:config interface.

Instead of an HTML Web page, the special preference system is displayed, using Firefox’s own XUL page display language. The about:config page is a bit like a dialog box, except that it sits inside the existing window, rather than a window of its own. In Figure 6.1, the page is displayed inside a single tab.

Some explanation of this interface is in order. Each line in the list reflects a single preference. You can see five such lines in Figure 6.1. Each preference has a name and a value. The Status column of a preference indicates whether it is set to the Firefox default value (default), or has been changed by the user to something else (user set). The Type column of a preference identifies the kind of data that preference holds.

Note

Preferences can be one of three types: string, boolean, or integer. String preferences are simply text strings (like “hello”), which include URLs (https://update.mozilla.org/extensions/?application=%APPID%). Boolean preferences are yes/no options; they hold either true or false. George Boole, a famous scientist, was the first to explain how to work with true/false values, so they’re also called “Booleans.” Integer preferences take on any integer value (such as 1, 2, 23, 1099), but can’t accept decimal numbers like 5.4.

At the top of the page you’ll see a Filter text field into which you can enter some text to filter out preferences. This is very handy, since the full list of preferences spans a good number of pages.

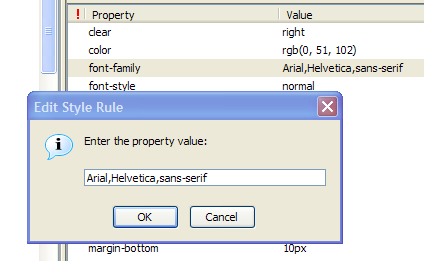

Modifying Preferences

Changing an existing preference is very simple. Just double-click on that preference’s line, or right-click on it and select Modify. The values of Boolean preferences will be automatically toggled (swapped from “true” to “false” or vice versa). Modifying string and integer preferences causes a dialog box to appear, prompting you for the new value for the preference.

As you make your changes, you’ll notice the status of the preference changing from default to user set, and that the preference text is displayed in bold type. This provides a clear indication of preferences that have been changed from the built-in browser defaults.

Among the hundreds of Firefox preferences there are some particularly handy ones that help to make Firefox even better than it already is. Let’s discover a few of these hidden gems.

Speeding up Firefox

Here’s a configuration tip that enables Firefox to download Web pages faster: enable HTTP pipelining. HTTP pipelining allows Firefox to send multiple requests at the same time, resulting in faster loading times for Web content. Note that more technical details on HTTP pipelining are available.

Warning

HTTP pipelining is an experimental feature and can cause some Web pages to display incorrectly if they’re not properly supported by the Web servers. While the speed improvements may be worthwhile, if your favorite Web pages start to look weird, try turning pipelining off again.

To enable pipelining, open the about:config interface and:

- Set the network.http.pipelining preference to “true” to enable HTTP pipelining for Web access that’s “direct connect.”

- Set the network.http.proxy.pipelining preference to “true” to enable HTTP pipelining when the Web is accessed via a proxy server. You only need to do this if you’re using a proxy server; your ISP or network administrator can tell you if that’s the case or not.

- Set the network.http.pipelining.maxrequests preference to a number between 1 and 8. This number is the maximum number of requests that Firefox may send out at any one time in a pipeline. I recommend it be set to the maximum of 8 initially, then test working backwards from there. (The maximum is 8 as specified by the HTTP 1.1 specification; don’t try to set it any higher, as this will have no effect.) Step the value down by one (first to 7, then to 6, and so on) each time you notice the page display having problems.

With this hidden preference, you have to restart Firefox entirely before you can determine if a speed boost has been gained.

Inline URL Auto-completion

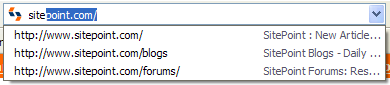

Here’s a useful hack to enable inline auto-complete for URLs. When this feature is working, whatever you type into the location bar is automatically completed by Firefox with the closest possible match that can be determined from the browser’s history. You can hit Enter when you get a match, or keep typing. This is much like the Inline AutoComplete feature in Internet Explorer. Figure 6.6 shows it at work.

Figure 6.6. Inline auto-completion in the location bar.

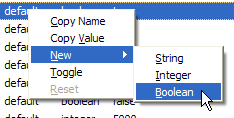

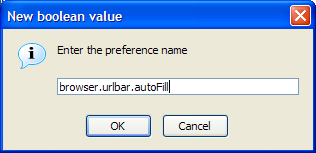

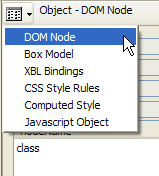

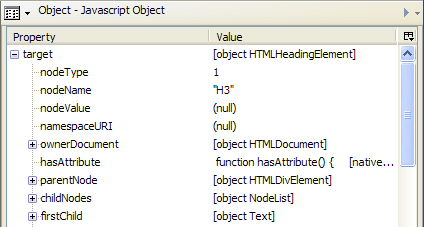

To enable this effect, you must add a preference that doesn’t yet appear in the about:config list. Go to about:config, right-click anywhere on the page, and select New > Boolean from the context menu, as shown in Figure 6.7.

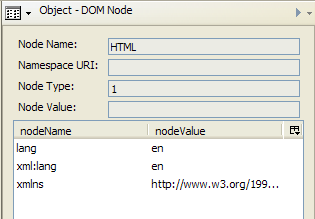

This menu choice yields a couple of dialog boxes. Enter browser.urlbar.autoFill when prompted by the first dialog box, as depicted in Figure 6.8.

Select true when you’re prompted to select a value, and that’s it: inline auto-complete for URLs is activated! There’s no need to restart Firefox in this case; it works straight away.

Figure 6.7. Creating a Boolean preference in about:config.

Figure 6.8. Naming the new preference.

Chapter 7 – Web Development Nirvana

Warning

This chapter is geared towards Web developers and designers, and assumes some knowledge of Website creation.

From its penchant for Web standards compliance, to its built-in Web developer-friendly features, and onwards across the amazingly useful plethora of Web development-oriented extensions, Firefox is, without doubt, a far more useful Web development tool than any other Web browser! Such hyperbole, is, in this case, entirely accurate.

Firefox’s checklist of useful tools is extensive. Friendly and actually useful JavaScript debugging tools – check. Provision of detailed Web page information – check. Real-time DOM inspector and editor – check. Ability to view HTTP headers as they are returned from a Web server – check. Validation of HTML, CSS, and accessibility conformance with minimal clicks – check.

Using extensions, you can even edit the CSS of a living, breathing Web page and observe the results immediately. It doesn’t even matter which Website the Web page comes from!

In this chapter, we’ll explore Firefox’s Web developer-friendly features. We’ll also delve into the extensions that make indispensable tools for so many Web developers (including myself: I’ve been a freelance Web developer since 2001 and I’m currently employed as a Java Web developer). Read on if you want your development work to proceed as smoothly and professionally as possible.

Firefox’s Standard Tools

You don’t need to buy or download anything to get started. Many useful tools lurk inside the standard Firefox install.

Viewing Source Fundamentals

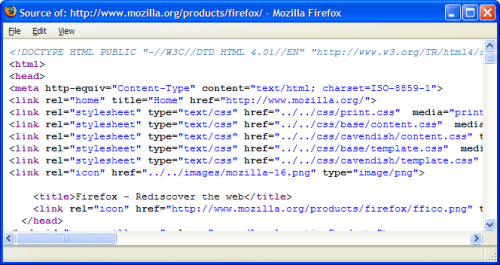

One of the first tasks with which many Web developers find themselves involved is examining the source of other people’s Web pages, whether for debugging purposes, as a learning aid, or simply to satisfy their own irrepressible curiosity. Firefox comes with a nifty page source viewer that offers built-in syntax highlighting. Highlighting makes it easier to read the HTML source, and simpler to grasp the implied structure of the page.

You can view the source of a page using the menu system: choose View > Page Source. Alternatively, right-click and choose View Page Source from the context menu, or hit Ctrl-U. Figure 7.1 shows the scrutiny of a typical page’s source; in this case, it’s the Firefox homepage on the Mozilla Website.

If you read and write HTML for a living, you probably already use an HTML editor that offers syntax highlighting. Modern browsers should perform to the same level. Yet Firefox’s support is far superior to simply opening a black-and-white Notepad session – the default action for Internet Explorer 6.0.

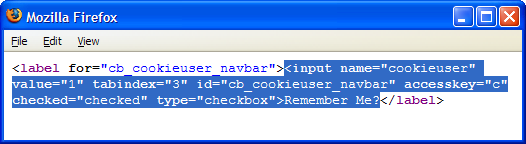

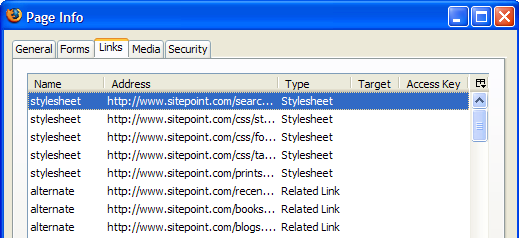

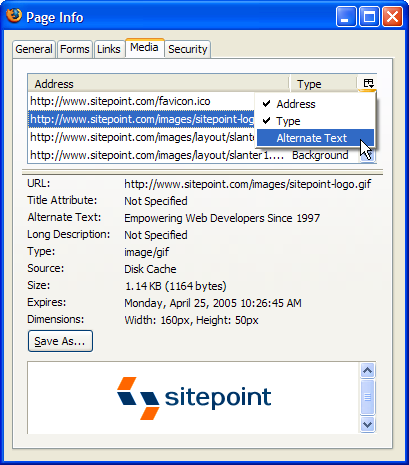

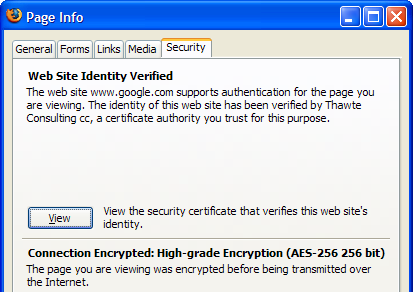

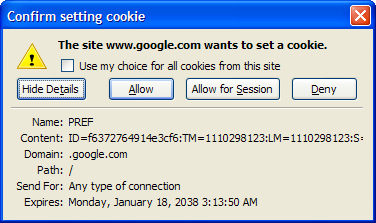

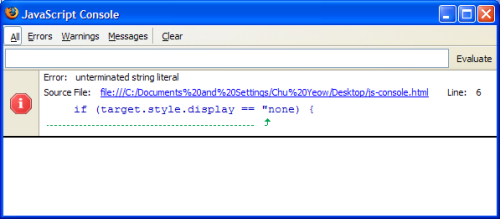

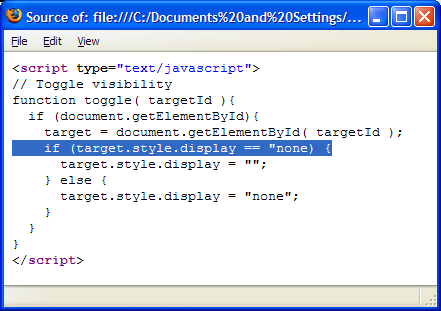

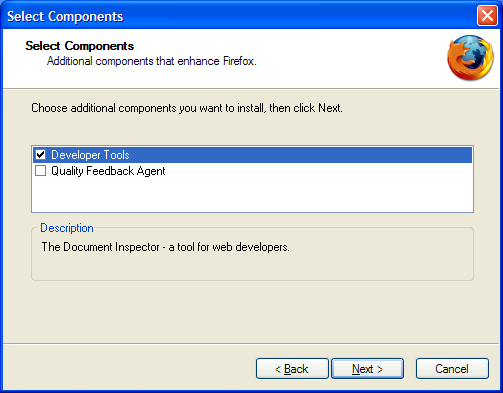

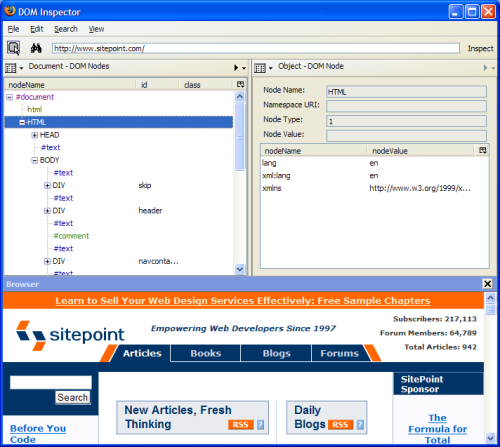

Viewing Selection Source