this keyword is the source of a lot of confusion for many developers every single day. Unlike a language with a rigid class model, it’s not always clear what this is going to refer to in your code, especially when dealing with callback functions, whose callsites you have no control over.

It’s trivial for some other code to rebind the context of the function you’re working with―using the new keyword and some of the methods that are built onto Function.prototype. This introduces an entire class of confusing scenarios and often you’ll see callback driven code scattered with calls to .bind(this).

The Problem

Because React uses thethis keyword to reference the component context inside each class, it also inherits this confusion. You’re probably used to seeing code like this inside React components.

this.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(function loaded() {

this.setState({ loading: false });

});

TypeError because this.setState is not a function. This is because when the callback to the promise is called, the internal context of the function is changed and this references the wrong object. Let’s take a look at the ways in which we can prevent this from happening.

The Options

Some of these alternatives are old techniques that have been used in Javascript for years, others are specific to React and some won’t even work in browsers yet, but we’ll explore them all anyway.1. Alias This

This is approach has been around for a lot longer than React and it involves creating a second reference to thethis at the top level of the component’s scope.

var component = this;

component.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(function loaded() {

component.setState({ loading: false });

});

2. Bind This

The next option we have involves injecting the correct context into our callback function at runtime.this.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(function loaded() {

this.setState({ loading: false });

}.bind(this));

this. Once a function has been “bound” the context can’t be overriden, meaning that we have a guarantee that this will refer to the correct thing.

This approach is a little bit harder to understand for other programmers and if you’re working with deeply nested, asynchronous code, then you’ll find yourself having to remember to bind each function as you go.

3. React Component Methods

React allows you to define arbitrary methods on your component classes and these methods are automatically bound with the correct context forthis when you create your components with React.createClass. This allows you move your callback code out onto your component.

React.createClass({

componentWillMount: function() {

this.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(this.loaded);

},

loaded: function loaded() {

this.setState({ loading: false });

}

});

.bind(this) onto a component method, then React will warn you that you’re doing unnecessary work.

bind(): You are binding a component method to the component. React does this for you automatically in a high-performance way, so you can safely remove this call.It’s important to remember that this autobinding doesn’t apply to ES2015 classes. If you use them to declare your components, then you’ll have to use one of the other alternatives.

4. ES2015 Arrows

The ES2015 specification introduces the arrow function syntax for writing function expressions. As well as being terser than regular function expressions, they can also have implicit return and most importantly, they always use the value ofthis from the enclosing scope.

this.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(() => {

this.setState({ loading: false });

});

(anonymous function).

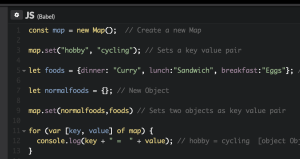

If you are using a compiler like Babel to transform ES2015 code into ES5, then you’ll that there are some interesting qualities to be aware of.

- In some cases the compiler can infer the name of the function if it has been assigned to a variable.

- The compiler uses the Alias This approach to maintain context.

const loaded = () => {

this.setState({ loading: false });

};

// will be compiled to

var _this = this;

var loaded = function loaded() {

_this.setState({ loading: false });

};

5. ES2016 Bind Syntax

There’s currently a proposal for an ES2016 (ES7) bind syntax, which introduces:: as a new operator. The bind operator expects a value on the Left-Hand Side and a function on the Right-Hand Side, this syntax binds the RHS function, using the LHS as the value for this.

Take this implementation of map for example.

function map(f) {

var mapped = new Array(this.length);

for(var i = 0; i < this.length; i++) {

mapped[i] = f(this[i], i);

}

return mapped;

}

map look like a member of our data instead.

[1, 2, 3]::map(x => x * 2)

// [2, 4, 6]

[].map.call(someNodeList, myFn);

// or

Array.from(someNodeList).map(myFn);

someNodeList::map(myFn);

this.setState({ loading: true });

fetch('/').then(this::() => {

this.setState({ loading: false });

});

.bind(this) (in fact, that’s what Babel compiles it to) and you’re forced to use it again and again if you nest your code. It’s likely to confuse other programmers of all abilities.

React component context probably isn’t the future of the bind operator, but if you are interested take a look at some of the great projects where it’s being used to great effect (such as mori-ext).

6. Method Specific

Some functions allow you to pass an explicit value forthis as an argument. One example is map, which accepts this value as it’s final argument.

items.map(function(x) {

return <a onClick={this.clicked}>x</a>;

}, this);

Conclusion

We’ve seen a range of different ways to ensure that you end up with the correct context in your functions, but which one should you use? If performance is a concern, then aliasingthis is probably going to be the fastest approach. Although you probably won’t notice a difference until you are working with tens of thousands of components and even then, there are many bottlenecks that would arise before it became an issue.

If you’re more concerned about debugging, then use one of the options that allows you to write named functions, preferably component methods as they’ll handle some performance concerns for you too.

At Astral Dynamics, we’ve found a reasonable compromise between mostly using named component methods and arrow functions, but only when we write very short inline functions that won’t cause issues with stack traces. This allows us to write components that are clear to debug, without losing the terse nature of arrow functions when they really count.

Of course, this is mostly subjective and you might find that you prefer to baffle your colleagues with arrow functions and bind syntax. After all, who doesn’t love reading through a codebase to find this?

this.setState({ loading: false });

fetch('/')

.then((loaded = this::() => {

var component = this;

return this::(() =>

this::component.setState({ loaded: false });

}).bind(React);

}.bind(null)));

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about JavaScript’s ‘this’ Keyword in React

What is the ‘this’ keyword in JavaScript and why is it important in React?

The ‘this’ keyword in JavaScript refers to the object it belongs to. It has different values depending on where it is used. In a method, ‘this’ refers to the owner object and in a function, it refers to the global object. In event handlers, ‘this’ refers to the element that received the event. The ‘this’ keyword is crucial in React because it helps us access the properties and methods of a component from within its methods.

How does the ‘bind’ method work with ‘this’ in React?

The ‘bind’ method in JavaScript creates a new function that, when called, has its ‘this’ keyword set to the provided value. In React, we often need to pass ‘this’ from a component to a function. The ‘bind’ method allows us to easily do this. It ensures that ‘this’ inside the function points to the correct object, which is especially important when working with event handlers in React.

Why do we need to bind ‘this’ in the constructor in React?

In React, class methods are not bound by default. If you forget to bind ‘this’ and pass it to an event handler, ‘this’ will be undefined when the function is actually called. This is not React-specific behavior; it is a part of how functions work in JavaScript. Binding ‘this’ in the constructor ensures that it refers to the same thing throughout the component, which is typically what we want in a React component.

What are the different ways to bind ‘this’ in React?

There are several ways to bind ‘this’ in React. The most common way is to use the ‘bind’ method in the constructor of a component. Another way is to use arrow functions, which automatically bind ‘this’. You can also bind ‘this’ in the render method, but this is less efficient because a new function is created each time the component renders.

What are the pros and cons of using arrow functions to bind ‘this’ in React?

Arrow functions automatically bind ‘this’, which can make your code cleaner and easier to understand. However, they can also be less efficient because a new function is created each time the component renders. This can lead to performance issues in large applications.

How does ‘this’ behave in arrow functions in React?

In arrow functions, ‘this’ is lexically bound. This means it uses ‘this’ from the code that contains the arrow function. So, for arrow functions, ‘this’ always represents the object that defined the arrow function. This is why arrow functions are often used in React, as they eliminate the need to manually bind ‘this’.

Can I use ‘this’ in functional components in React?

No, ‘this’ is not accessible in functional components in React. This is because ‘this’ is not defined in functional components. If you need to use ‘this’, you should use a class component instead.

What is the performance impact of binding ‘this’ in the render method in React?

Binding ‘this’ in the render method can lead to performance issues. This is because a new function is created each time the component renders. In large applications, this can lead to significant performance degradation.

How can I avoid binding ‘this’ in the constructor in React?

One way to avoid binding ‘this’ in the constructor is to use arrow functions. Arrow functions automatically bind ‘this’, so you don’t need to bind it manually. Another way is to use class properties, which are a stage 3 proposal for JavaScript.

What is the difference between ‘this.props’ and ‘this.state’ in React?

this.props’ and ‘this.state’ are both special attributes in React. ‘this.props’ is used to pass data from parent to child components, while ‘this.state’ is used for data that is going to change. ‘this.props’ is read-only, while ‘this.state’ can be updated.

Digital Nomad and co-founder of UK based startup Astral Dynamics.