Working on a new project is fun and feels super productive. Features can be added quickly and prototyping ideas leads to a tight feedback loop ideal for Agile/Lean-esque planning.

However, as time goes by, I found that the initial momentum enjoyed early on in the project decreases and doing test-first development of Rails applications becomes difficult. In contrast, when writing libraries a test-first approach seems natural.

The predominate voice in the Rails community advocates the so-called “Rails Way”. This is the golden prescribed path, the reason many of us, no doubt, took to Rails in the first place. It’s the beauty of Rails and its famed productivity boosts.

But somehow these gains seemed frustratingly short lived.

After working on several none-trivial Rails applications, I began to recognise the symptoms and by listening to others I began to piece together the causes of my frustration.

Working on a new project is fun and feels super productive. Features can be added quickly and prototyping ideas leads to a tight feedback loop ideal for Agile/Lean-esque planning.

However, as time goes by, I found that the initial momentum enjoyed early on in the project decreases and doing test-first development of Rails applications becomes difficult. In contrast, when writing libraries a test-first approach seems natural.

The predominate voice in the Rails community advocates the so-called “Rails Way”. This is the golden prescribed path, the reason many of us, no doubt, took to Rails in the first place. It’s the beauty of Rails and its famed productivity boosts.

But somehow these gains seemed frustratingly short lived.

After working on several none-trivial Rails applications, I began to recognise the symptoms and by listening to others I began to piece together the causes of my frustration.

The Inspiration

I first heard of Hexagonal Rails in a talk by Matt Wynne at GoRuGo 2012. I immediately recognised the problems he described in my own code, particalluy controllers written in a procedural style, littered withif statements. Matt shows how to overcome this using the pub-sub pattern, which is what I will be demostrating in this article.

The idea behind Hexagonal Rails is the separation of the core application from the delivery mechanism, something echoed in the keynote talk, “Architecture the Lost Years”, by Robert Martin and “Objects on Rails” by Avdi Grimm.

The take away idea is your app is not a Rails app. Rails is nothing more than a framework used to wrap your app in the HTTP protocol. It’s a detail and we should be concerned with Object-Orientated development, not Rails-orientated development.

Yet Another Ebay Clone

Imagine we are working for a startup that is building an ebay clone for a niche market. On the product pages someone can bid on an item by entering an amount and pressing a “Bid Now” button. In the beginning, the story is very simple; create a new bid and let the user know if it was successful or not. Easy, use the “Rails Way”, deliver and ship. Agile-ing-hell-fire. Sometime later, new stories are added to the backlog:- Email the seller of the item

- Update the UI of item watchers in realtime

- Store a statistic

- Update the activity feeds for all subscribers of the item

CreateBid. It sounds like it would be a good candidate for a new object that models the creation of a bid.

This type of object is often refereed to as a service, use case, or command. I will use the word ‘service’.

Services are typically used to orchestrate interactions across multiple models and/or interact with external systems (e.g. HTTP and SMTP).

A service object seems like a good idea, but haven’t we just moved the problem?

Aren’t our services just going to get bloated like out models? Yes!

Wispered Service Objects

Wisper is a library which supplements Ruby’s Methods and Attributes with Events. We will use it to allow our service objects can publish events to other objects in a decoupled manner. The service object can perform its primary action and then broadcast the outcome, an event, to any listeners. Listeners are added to the service object within the context in which the service is executed, in this case, the context is the controller. Lets take a look at an example: The controller:class BidsController

def new

@bid = Bid.new

end

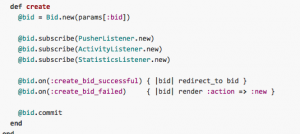

def create

service = CreateBid.new

service.subscribe(WebsocketListener.new)

service.subscribe(ActivityListener.new)

service.subscribe(StatisticsListener.new)

service.subscribe(IndexingListener.new)

service.on(:reserve_item_successfull) { |bid| redirect_to item_path(bid.item) }

service.on(:reserve_item_failed) { |bid| @bid = Bid.new(bid_params); render :action => 'new' }

service.execute(current_user, bid_params)

end

private

def bid_params

params[:bid]

end

endclass CreateBid

include Wisper::Publisher

def execute(performer, attributes)

bid = Bid.new(attributes)

bid.user = performer

if bid.valid?

bid.save

notify_seller_of(bid)

broadcast(:bid_successful, performer, bid)

else

broadcast(:bid_failed, performer, bid)

end

end

private

def notify_seller_of(bid)

BidMailer.new_bid(bid).deliver

end

endclass WebsocketListener

def bid_successful(performer, bid)

Pusher.trigger("item_#{bid.item_id}", 'new_bid', :amount => bid.amount)

end

end

class ActivityListener

def reserver_item_successful(performer, bid)

# ...

end

endif‘s, is very readable, and has a pleasing shape.

We have moved the auxiliary concerns (websocket notifications, activity feed) in to seperate objects.

The controller (context) does the following:

- Creates a service object

- Wires up any listeners that need to know about the response

- Executes the service passing in data pulled from the HTTP request

CreateBid does not tell listeners to do something, its tells them something happened. This is subtle but important. CreateBid does not know the context in which it is being executed (it might not be a web app) or who is listening. Objects which trust, not control, others only need to make choices based on their own state. This creates a clear boundary between objects and their responsibilities and does not constrain choices we can make in the future about how use our domain objects.

If we need to add a new feature as part of the registration process we have a two choices:

- Add code to the service object. Appropriate if the feature is intrinsically part of the use case being expressed by the service. In my example I decided sending an email is part of registration process.

- Add a listener to the service object. Most appropriate if the feature is auxiliary to the use case expressed by the service, should not happen in all circumstances in which the service is executed and/or is specific to the delivery mechanism.

Publishing events

Simply includeWisper::Publisher in any object to allow it to publish events.

class MyPublisher

include Wisper::Publisher

def do_something

publish(:done_something, 'hello', 'world')

end

endpublish is called done_something will be called on all listeners which have (respond_to?) this method. The method must have an argument signature which can accept the arguments being published, so in the above example a listener should have:

def done_something(greeting, location)

# ...

endpublish method is also aliased as broadcast and emit.

Subscribing to events

my_publisher = MyPublisher.new

my_publisher.subscribe(MyListener.new)create_bid.subscribe(WebsocketListener.new, :on => :bid_successful)on if you need to specific multiple events.

If the listener has a method which does not match the name of the event being broadcast you can map it a different method name using with.

create_bid.subscribe(BidListener.new, on => :bid_successful, :with => :successful)create_bid.subscribe(self), but adding a block makes it look more Rails-ish.

create_bid.on(:reserve_item_successfull) do |reservation|

redirect_to reservation_path(reservation)

endGlobal Listeners

Wisper also allows adding of “global listeners” which are automatically subscribed to every publisher. In a Rails application I would typically add global listeners in an initalizer.Wisper::GlobalListeners.add_listener(StatisticsListener.new)In Summary

By combining Service objects with Wisper we get the following benefits:- Smaller objects with fewer responsibilities

- Objects can be wired up based on context in a lightweight manner

- The core application is not polluted with the delivery mechanism concerns

- Objects tell listeners what happened, not what to do (trusting, not controlling)

- Isolated testing is easier and because we can do away with requiring Rails tests run faster.

- Clear boundaries exist between objects in different layers.

- Moving to async is easier since we can execute from a background job without Rails loaded

Refactoring mature codebases

Luckily this concept is very easy to apply to a mature code base in stages, partcularly if you have good test coverage. Simply choose somewhere to start, like a bloated model or a crazyif laced controller.

As I developed Wisper, I tried many techniques for implementing Pub-Sub in my code and it still contains some of those experiments. I only replace them with Wisper when I need to touch the controller in question for some other reason.

Once a model or service object has Wisper in place, adding new listeners is very easy. For example, caching can be moved out of the model/observer/controller and in to a listener.

You can even apply Wisper to an ActiveRecord model as easily as any other object if you wish to remove some after_ callbacks.

Have a go, find one place in your Rails app that needs some TLC and create a branch. See if it works out for the better.

I’d love to hear how you get on, your thoughts and feedback on Github, in the comments or on Twitter.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Using Wisper to Decompose Applications

What is the main purpose of using Wisper in application decomposition?

Wisper is a micro library that provides an easy-to-use and flexible way to implement the publish-subscribe pattern in Ruby. It allows objects to subscribe to events and react to them, which can be particularly useful in decomposing applications. By using Wisper, you can create loosely coupled, highly cohesive components that communicate through events, making your application easier to maintain and extend.

How does Wisper compare to Rails Observers?

While both Wisper and Rails Observers allow for event-driven programming, they have some key differences. Rails Observers are tightly coupled to the ActiveRecord lifecycle, which can lead to complex and hard-to-maintain code. On the other hand, Wisper provides a more flexible and decoupled approach, allowing any object to publish and subscribe to events, not just ActiveRecord models. This makes it a better choice for decomposing applications into smaller, more manageable components.

How do I install and set up Wisper in my Ruby application?

To install Wisper, you simply need to add the gem to your Gemfile and run the bundle install command. Once installed, you can include the Wisper::Publisher module in any object that you want to publish events. Subscribers can then listen to these events and react accordingly. The setup process is straightforward and well-documented, making it easy to get started with Wisper.

Can I use Wisper with ActiveRecord?

Yes, you can use Wisper with ActiveRecord. There is a separate gem called wisper-activerecord that provides integration between Wisper and ActiveRecord. By using this gem, you can automatically publish events for ActiveRecord lifecycle events such as create, update, and destroy. This can be particularly useful in larger applications where you want to decouple ActiveRecord models from other parts of your application.

What are some common use cases for Wisper?

Wisper can be used in a variety of scenarios where you want to decouple components of your application. Some common use cases include background processing, caching, logging, notifications, and auditing. By using Wisper, you can create a more modular and maintainable application architecture.

How do I handle errors in Wisper?

Wisper provides several ways to handle errors. You can define error handlers that will be called when an error occurs during the execution of an event. You can also use the on_error method to specify a block of code that will be executed in case of an error. This gives you a lot of flexibility in handling errors and ensuring that your application remains robust and reliable.

Can I use Wisper in a multi-threaded environment?

Yes, Wisper is thread-safe and can be used in a multi-threaded environment. It uses a thread-local storage for its event listeners, ensuring that events are delivered to the correct listeners even in a multi-threaded context. This makes Wisper a good choice for applications that need to handle concurrent requests or perform background processing.

How do I test Wisper events in my application?

Testing Wisper events is straightforward. You can use the broadcast method to trigger an event and then assert that the expected listeners have been called with the correct arguments. Wisper also provides a Wisper::Testing::RSpec::BroadcasterMatcher that you can use in your RSpec tests to make testing even easier.

Can I use Wisper with other Ruby frameworks?

Yes, Wisper is not tied to any specific Ruby framework and can be used with any Ruby application. It is a standalone library that provides a simple and flexible way to implement the publish-subscribe pattern, making it a good choice for any Ruby application that needs to decompose its components.

How do I debug Wisper events?

Debugging Wisper events can be done by using the Wisper::EventListener module. This module provides a listening_to method that you can use to log all events that are being listened to. You can also use the on method to log specific events. This can be particularly useful in tracking down issues and understanding the flow of events in your application.

Freelance Rubyist