There exists a debate within the User Experience community about whether a user interface should say ‘Your account‘ or ‘My account‘ to refer to the user's account. Should the call to action be ‘Create your account‘ or Create my account?

Pinterest and Trello are both social web apps that use "boards", yet see how they differ!

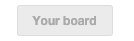

Pinterest: YOUR Board button

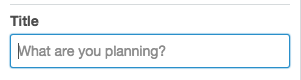

Trello: MY Boards button

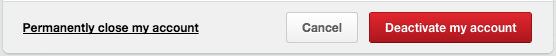

When it comes time to delete your account, however, they both switch terms:

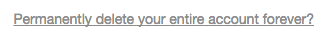

Interestingly, they agree on prompts:

Pinterest: What’s YOUR board about?

Trello: What are YOU planning?

So how are you to decide? One trick is to consider who is in the room and who is talking.

There's No One in the Room Except the User

If there's no one else in the room, skip the qualifier entirely. There's no ambiguity. That is, if your user has no reason to acknowledge your brand or anyone else, imagine they're in an empty room. If there's a wrapped present on the table in this empty room, they know it's for them without needing a gift tag and their name on it.

When you avoid the qualifier, you gain the benefit of front-loading interface copy with distinguishing words instead of "your" or "my". For example, "Privacy settings" stands out from "Account" better than "My privacy settings" from "My account". This makes your user interface easier to scan. It also reduces the time it takes a user to understand what they're seeing and take their next action (perhaps, buying your product).

Two's Company — the website and the user

Only use "your" or "my" when you need to differentiate between the user and the website speaking:

- When the website is talking, use "Your".

- When the user is talking, use "My".

In the first instance, the website may "speak" to:

- Orient the user through page headings and labels

- Provide content

- Tell the user about their content

- Tell the user there's been an error and how that affects them

- Provide help and instructions

- Offer documentation

(This is often expressed through some kind of label — a page label, form label, button label — so for simplicity we'll refer to this type of dialog as a label.)

In the second instance, the user "speaks" when they perform actions. That is, the user lets the website know what they want by:

- Pressing buttons

- Clicking menu items

- Entering data

- Selecting filters

- Otherwise making some choice and commanding the website

(For simplicity, we'll focus on buttons.)

As such, "My" is appropriate in actions.

Using "Your" or "My" when there are multiple voices removes the ambiguity about who is talking and who they are addressing, however, you still don't need to use both at all times. Assume one person is always talking, then add the qualifying "your" or "my" for exceptions when you need to differentiate between the website and user.

If the default is that the user is talking, you need to specify when the website is interjecting:

- Website: “Would you like free gift wrapping with your purchase?” (label)

- User: “Add gift wrapping” (button) — not “wrap my gift”

- Website: “Your Clients:” (label)

- User: “Contact Clients” (button) — not “Contact My Clients”

If the default is that the website is talking, you need to specify when the user speaks up:

- Website: “Gift wrapping:” (label) — not “Wrap your gift:”

- User: “Wrap my gift” (button)

- Website: “Clients:” (label) — not “Your Clients:”

- User: “Contact My Clients” (button)

Whether you emphasize the website's voice or the user's voice may depend on your product or service. A chatty, engaging brand will use "your" extensively. Alternatively, in personal, individual environments, a brand may wish to hide their presence. For example, consider these buttons:

- "Check My Bank Balance"

- "Update My Medical Records"

- "Create My Account"

Don't draw attention to other people in the room by saying "Let's review your medical records." It's awkward.

If you decide to emphasize both voices to highlight the interaction and create a social experience, there's one particular complication I want to highlight: combining labels and buttons, which mixes voices. Let's look at 2 examples.

Firstly, navigation links are sometimes treated as buttons that indicate the user's intent, for example, clicking "My Stuff" in the main navigation menu to "Go to My Stuff". The following page is then labeled "Your Stuff". While on this page, you can see the "My Stuff" nav button and "Your Stuff" page label. Together, this appears inconsistent:

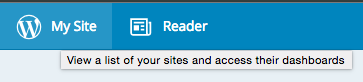

Instead of providing a button labeled "My Site", WordPress could say "Your Sites" or label it with the name of the site in question (which is the page label for the subsequent page when you click that button).

Treating navigation links as a label to show the user where they are and as an button when a user clicks it to navigate combines the website's voice and the user's voice into one button.

Secondly, social media buttons such as "Follow me on Twitter" typically express the user's intent to perform an action despite speaking in the website's voice. This wording, however, makes more sense than the user clicking on "I want to follow you on Twitter" or "Follow them on Twitter". The convention used in "Follow me on Twitter" is akin to the website asking, "Would you like to follow me on Twitter?" and the user answering, "Yes", where the question and answer are condensed into one button.

To handle these cases, write the button's text using the website's voice. This avoids apparent inconsistency between page and navigation labels, as well as conforming to convention for social media buttons. Alternatively, separate the label and action out from the one button.

Meanwhile, you only need to differentiate voices when the website may validly be speaking. There's no need to offer the user a button to "Update My Membership" when the website won't have its own "membership". Similarly, showing "Your Cart:" is often unnecessary because the website doesn't have its own cart, and the user doesn't know what's in other users' carts. "Cart" would do just fine.

Three's a Crowd — Many Users

When your user engages with other users through your website, stick to the guidelines above — "your" for labels, "my" for buttons — and extend the concept to express other users' voices.

- Labels: "Your Photos:" and "Your friend's photos:"

- Buttons: "Tag Photos" (lets you tag any photos; note how it's intentionally ambiguous), "Tag My Photos", and "Tag My Friends' Photos"

Imagine you are an administrator of a business system. You're responsible for: system functionality, moderators or staff that use the system, end users of the system, and how you use the system. You might see:

- "System Settings:"

- "Staff Settings:"

- "User Settings:"

- "Your Settings:"

In "Staff Settings:", you might see an "Update Staff Settings" button. In "Your Settings:", you might see "Update My Settings".

After a point though, if your users have control over other people's things, you will need to start using names. If you have a shared account, for example, "my" could refer to anyone in the account:

Bill Scott, the lead UI Engineer at Netflix (and a renowned patternista himself) tells me that at Netflix they avoid “Your,” preferring “Bill’s recommendations.” Their rationale is that it communicates the personalization (the same way “your” and “my” are supposed to), and it also clarifies that “it is you and not your kid (when using multiple profiles in a household).” But then again, for most people Netflix may be more of a personal utility than a social environment. — Designing Social Interfaces: Your vs. My

Similarly, a gift card could be "your gift card" because you bought it to give to someone, or "your gift card" because it was given to you to spend. Using names removes ambiguity.

As one of many system administrators, you might be able to see "Sheldon's Settings" and hit the "Update Sheldon's Settings" button.

Conclusion

In summary, if you don't absolutely need to use "your account" or "my account", don’t use either, use: "account". If you must use "your" or "my" to indicate who is talking, use "your" for labels, and use "my" for buttons sparingly. If the interface is private or personal, use "my" for buttons, and use "your" for labels sparingly. If there are many users, address people by name.

And if all else fails, be consistent!

Diana MacDonald

Diana MacDonaldDiana is a professional Jill of all trades. Her digital work reflects her honesty, attention to detail, and appetite for new technology. Some say it's like a subtle cool breeze on a warm Summer's day. You might find her on Twitter, but she doesn't say much because she's shy.