Key Takeaways

- A masked password field is a solution to the issues with traditional password fields, obscuring all characters except the last one, providing a balance between security and usability.

- The script to create a masked password field is complex, involving several browser-related and usability considerations, and requires a careful balance of event listeners to respond to user input.

- The implementation of a masked password field is not straightforward, requiring the script to limit the caret position, handle how browsers treat the value contained in the field, and manage additional behaviors to control the field.

- While a JavaScript solution for masked password fields has its limitations, the author suggests that browsers should implement this kind of field as an input type in its own right, highlighting the need for a balance between security and usability.

Platform Solutions

Away from the Web, various platform solutions have been presented. Mac OS wireless-password fields have a “Show password” checkbox next to them, which allow you to view it in plain text; we’ll be looking at that solution for the next post in this series. In this post we’re going to look at a solution more common among handheld devices. Recent Symbian and Android devices do this, but it’s arguably more commonly known on the iPhone and iPod touch.The Masked Password Field

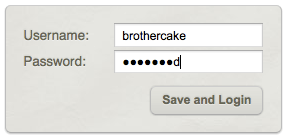

A masked password field obscures all the characters except the last one, which is visible as plain text. So you can always see what you’re typing, but the whole password is never revealed, making it near-impossible to read surreptitiously: A login form with a masked password field.

A login form with a masked password field.

"password" fields.

The script is quite complex. The core of what it does is simple, but there are several browser-related and usability gotchas to consider, and these add some complications. So while I’ll try to give you a good sense of how it all works, this is less a how topost, and more a

whether tooverview. The real nitty-gritty is in the script itself, which is extensively commented with details of what does what, and why. Have a look at the demo and grab the script. It works in all modern browsers, including IE6:

First: the Markup

To begin with, we need a"password" type field. We have to do this as a progressive enhancement, so that unsupported or no-script browsers still have a proper password field:

<label for="pword">Password:</label>

<input type="password" id="pword" name="pword" />"text" field, as well as creating a second, "hidden" field. The hidden field is where we’ll store the plain, unencrypted version of the password, while the visible field is what users type into, and where the masked password is shown.

So this is what the markup will ultimately become:

<label for="pword">Password:</label>

<span>

<input type="hidden" name="pword" />

<input type="text" class="masked" id="pword" autocomplete="off" />

</span>name attribute, so that it’s the only one to be submitted. The visible field is what users see, but its value would be junk to any other process, so we stop it from being submitted, and (crucially) don’t allow autocomplete to remember it either (because all it would remember is a series of dots, with no way of decoding them).

Originally, I had an elegant process for doing this markup conversion, but naturally enough it failed to work in IE

. In Internet Explorer, even the latest version, you’re unable to modify the "type" attribute of a password field, or set the "type" of any form field that was generated in the DOM. The only way to create form fields in IE is to write them out in source text and inject it into the page with innerHTML! It’s ugly, I know, but it’s what it takes to make this work.

Then: the Events

Once we have the markup, we need to handle its events; we have to be able to respond to any kind of input, whether it’s by keyboard, mouse, or some programmatic means. There are so many ways, in fact, that it would be impossible to cater for them all in advance; but we can catch the changes retrospectively, and modify the value just after it’s been input. As long as we do it fast enough, users should be unable to notice the difference. To achieve this the script uses four event-listeners. The first two provide a solid foundation, being the most robust and cross-browser compatible; these are:onkeyup to catch primary keyboard input, and onchange to catch secondary input such as pasting from the mouse.

Then we supplement them with some nonstandard events that are similar to onchange, but which respond immediately instead of waiting for the field to lose focus; these are: oninput (which works in the latest builds of the top browsers apart from IE), and onpropertychange (which is IE-only). We have to be careful with these events, though, because they also fire instantly from programmatic input; we therefore must watch that our code doesn’t create an infinite loop, by causing an event that it also responds to.

So with that spread of event listeners, we’ve covered every base and can respond to user input by any method, virtually instantly in most cases. And when we do respond, that’s when the masking happens.

When new input arrives in the text field, the first task is to extrapolate the entire plain password from the data we already have, plus the new input. For example, if the hidden field contains the value "passw" and the text field now has the value "●●●●wo", we can extrapolate–by counting letter by letter, from the first–that the new value is "passwo"

. Once we have that, we encode the whole value and write it back to the visible field so that it now says "●●●●●o", at the same time as updating the hidden field with the plain version, "passwo". (The dots themselves are a unicode character, 25CF, which is what most browsers use for regular password fields.)

This is a repeating, reciprocal process: new input triggers decoding, which triggers re-encoding, and by this process we continually have both a masked and a plain version of the password; the form can be submitted at any time, and the hidden field will always reflect the masked value you can see.

Now for the Gotchas!

As we’ve just seen, encoding and decoding of the masked password happens by comparing two values character by character, but we can’t do that unless we know which character equates to which; for example, the dot at index[0] corresponds with the letter at the same index. Ultimately, we can’t allow users to input characters at the beginning or middle of the password because that would break the equation; it’s only when input is limited to the end that we can know how the characters equate.

To implement this we have to limit the caret position, so the script has a routine which does precisely that–whenever the field has focus, it continually forces the caret to be at the end–so you can edit or select from the end, but not from the beginning or middle.

We’ll also encounter some security issues with regard to how browsers treat the value contained in the field. Since the field we’re working with is just a "text" field, browsers give it no special consideration. With real "password" fields, there are limits placed on how values carry over; for example, user input into a password field is not retained after soft refresh, or when coming back in the history; but with ordinary text fields, it is (or may be).

So we have to implement additional behaviors to take control of this. The script will delete any default value from the original field, and also trigger a reset() event to remove any residual input after soft refresh. (You’ll also remember how we had to disable autocomplete on the field, because the value the browser would try to remember is just a bunch of dots.)

All things considered then, this implementation is far from straightforward. Like I said at the start–the core of it is simple, but the devil, as always, is in the detail.

Conclusion

A JavaScript solution for this is probably impossible to implement without any side effects. The browser is set up to deal with"text" fields at a lower level of security than "password" fields, and this difference is why extra hacks were needed to bring the masked field up to the same level. But more fundamentally, we need to break the physical link between the data in the visible field and its counterpart in the hidden field in order to remove the input restrictions, and that really requires a lower-level implementation (for example, being able to store data as properties of an individual character).

I think this kind of password field is a good idea, but browsers should be implementing it as an input type in its own right.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Masked Password Fields

What is the purpose of password masking?

Password masking is a security feature that hides the actual characters of a password when a user types it into a password field. Instead of displaying the actual characters, the system shows a series of dots or asterisks. This feature is designed to prevent shoulder surfing, a technique used by attackers to steal passwords by looking over a user’s shoulder as they type.

How does password masking affect user experience?

While password masking enhances security, it can sometimes negatively impact the user experience. Users may make more errors when entering their passwords because they can’t see what they’re typing. This can be particularly problematic on mobile devices where typing errors are more common. However, many platforms now offer a “show password” option to balance security and usability.

What is a password mask attack?

A password mask attack is a type of brute force attack where the attacker knows some of the characters in a password. This knowledge reduces the number of possible combinations and makes the attack faster and more efficient. The attacker may have obtained this partial information through various means, such as phishing, social engineering, or observing the user.

Are there alternatives to password masking for protecting user passwords?

Yes, there are several alternatives to password masking. These include two-factor authentication, biometric authentication, and passwordless authentication. Two-factor authentication requires the user to provide two forms of identification, typically something they know (like a password) and something they have (like a mobile device). Biometric authentication uses unique physical or behavioral characteristics, such as fingerprints or voice patterns. Passwordless authentication uses a link or code sent to the user’s email or mobile device.

How can I implement password masking in my application?

Password masking can be implemented in various ways depending on the programming language and platform you’re using. In HTML, for example, you can use the input type “password” to create a password field that automatically masks input. In other languages, you may need to write additional code or use a library that provides this functionality.

Is password masking still necessary with modern security measures?

While modern security measures like two-factor and biometric authentication provide additional layers of protection, password masking still plays a crucial role in protecting user passwords. It’s a simple and effective way to prevent shoulder surfing and should be used in conjunction with other security measures for optimal protection.

Can password masking be bypassed?

Yes, password masking can be bypassed by various methods, such as using a keylogger to record keystrokes or exploiting vulnerabilities in the application. However, these methods require a higher level of technical skill and access to the user’s device or network.

Does password masking protect against online attacks?

Password masking primarily protects against physical attacks, like shoulder surfing. It does not protect against online attacks like phishing, keylogging, or brute force attacks. To protect against these types of attacks, additional security measures like two-factor authentication, secure password practices, and regular software updates are necessary.

What are the drawbacks of password masking?

The main drawback of password masking is that it can lead to more typing errors, especially on mobile devices. This can frustrate users and lead to more password reset requests. However, many platforms now offer a “show password” option to mitigate this issue.

How does the “show password” option work?

The “show password” option allows users to toggle the visibility of their password. When selected, the password field displays the actual characters instead of dots or asterisks. This can help users avoid typing errors, but it should be used with caution, especially in public or shared spaces where others might see the screen.

James is a freelance web developer based in the UK, specialising in JavaScript application development and building accessible websites. With more than a decade's professional experience, he is a published author, a frequent blogger and speaker, and an outspoken advocate of standards-based development.