Understand Design Thinking

1.1 What needs are addressed in the Playbook?

As described in the Introduction, we wanted to write a book for all those interested in innovation, for movers and shakers as well as entrepreneurs who design digital and physical products, services, business models, and business ecosystems as part of their work. Regarding our three personas, we were able to identify three very different kinds of users who apply design thinking in their day-to-day activities. One thing the three have in common, though: All three of them want to create something new in a rapidly changing world. Which brings us straight to our initial question:

How can we learn more about a potential user and better uncover his or her hidden needs?

In the individual chapters, we focus on the three personas of “Peter,” “Lilly,” and “Marc.” We hope this lets us address the needs of design thinking practitioners as best as possible.

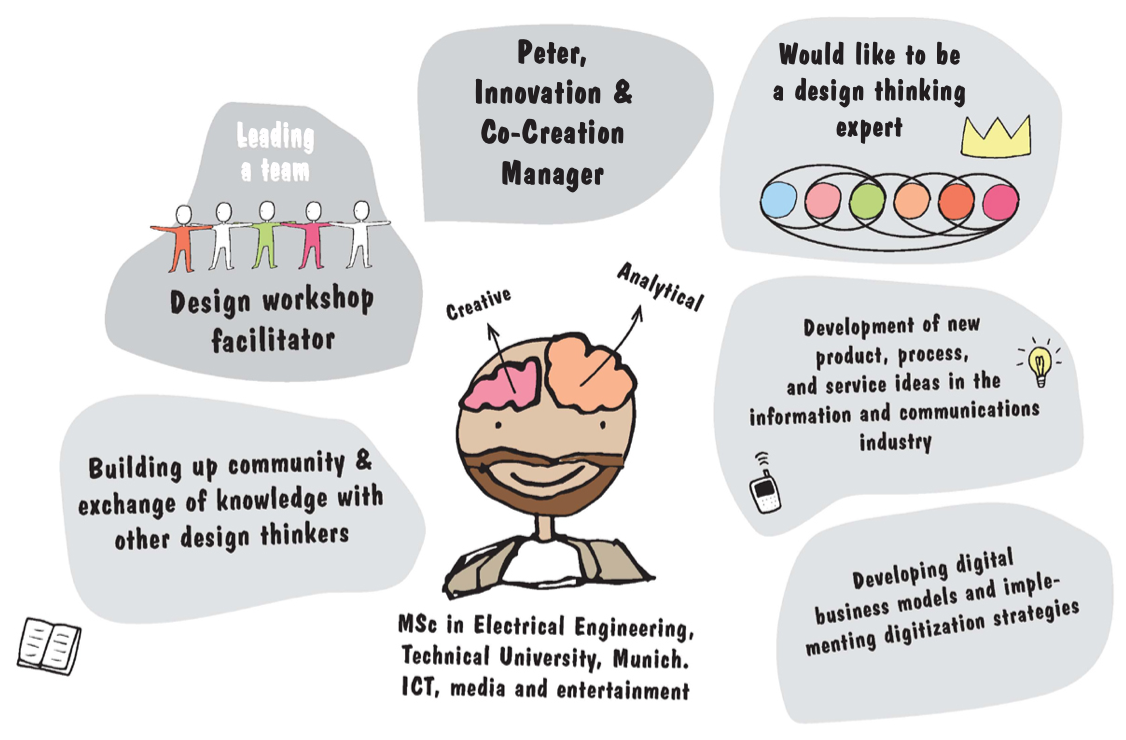

“Who is Peter?”

Peter, 40 years old, works at a large Swiss information and communications technology (ICT) company. Peter came in contact with design thinking in the context of a company project four years ago. Peter was a product manager then. Searching for the next major market opportunity, he had already tried out quite a few things. For a while, Peter always wore red underwear on New Year’s Day, but it didn’t make him any luckier in terms of successful innovations. After this experience, he doubted at first whether design thinking was really something for him. It was hard for him to imagine that something useful could come out at the end of the described procedure. The approach seemed just a little esoteric to him.

His attitude changed after he attended a number of co-creation and design thinking workshops with customers. He felt the momentum that can come into being when people with different backgrounds tackle complex problems together in the right environment. Paired with a good facilitator who provides work instructions in a targeted manner, any group can be empowered to create a new experience for a potential user. This positive experience prompted Peter to take on the role in such design thinking workshops as a facilitator. Owing to the workshop experience he had gotten and its successful implementation in projects, Peter was promoted not long ago. He now has the privilege of calling himself an “Innovation & Co-Creation Manager.”

He is glad to meet like-minded spirits at events such as “Bits & Pretzels” in Munich or design thinking meetings in Nice, Prague, or Berlin where he can exchange thoughts and ideas with the who’s who among digitization evangelists.

More about Peter: What is his background experience?

Peter studied at the Technical University of Munich. After graduating, he held various positions in the telecommunications, IT, media, and entertainment industries. Five years ago, he decided to move from Munich to Switzerland. Its location and excellent infrastructure convinced him to make this daring change. There, Peter met his future wife, Priya. He has been happily married for two years. She works for Google at their corporate campus in Zurich. Priya is not allowed to talk much about the exciting topics she works on, although Peter would be quite intrigued by them.

Both like to get involved with new technologies. Be it the smart watch, augmented reality, or using what the sharing economy has to offer, they try out everything the digital world comes out with. A few weeks ago, Peter had his dream of getting a Tesla come true. Now he is waiting for his car to be self-driving soon so he can enjoy the beautiful landscape while looking out the window. In his new role as Innovation & Co-Creation Manager, Peter now belongs among the “creative” ones. He has replaced his suits and leather shoes with Chucks.

Peter tried to resolve the last crisis in his relationship with a little design thinking session. Priya was very aloof with Peter all of a sud- den. Peter took the time to listen to Priya and better understand her needs. Together, they discussed ways to bring more oomph into their relationship. During the brainstorming, Peter had the idea that wearing his lucky red underwear might save the relationship. But in the meantime, he had developed so much empathy for Priya’s concerns that he quickly dismissed the idea. In the end, they came up with a couple of good ideas for their relationship. Priya did wish, though, that Peter would use a different method to learn his needs besides design thinking.

Up to now, Peter had used design thinking in various situations. He learned that the approach sometimes worked very well for reaching a goal, but that sometimes it wasn’t right. He would like to get a couple of tips from experienced design thinkers to shape his work even more effectively.

Visualization of the persona

User profile of an experienced design thinker from actual practice:

Pains:

- Peter’s employer does not invest much in the further training of employees.

- Although Peter feels quite competent by now in dealing with design thinking, he is still convinced he could get more out of the approach.

- Peter has noted that, while design thinking is a powerful tool, it is not always used optimally.

- Peter frequently wonders how the digital transformation might be accelerated and what design criteria will be needed in the future to be a success on the market.

- Peter would like to combine other methods and tools with design thinking.

- Peter is faced with the challenge of having to impart to his team a new mindset.

- He would like to exchange ideas with other design thinking experts outside his company.

Gains:

- Peter has a lot of leeway in his daily work to try out new methods and tools.

- He loves books and all tangible things. He likes to use visualizations and simple prototypes for explaining things.

- What he would really like to do is establish design thinking in the whole company.

- He knows various management approaches he would like to link with design thinking.

Jobs-to-be-done:

- Peter has internalized the design thinking mindset., but sometimes, good examples that would help to change his environment don’t come easily to him.

- Peter enjoys trying out new things. With his engineering background, he is open to other approaches to problem solving (whether quantitative or analytical).

- He would like to become an expert in this environment as well. He is looking to connect with like-minded individuals.

- Peter experiments with design thinking.

Use cases:

A book in which experts report on their experience, in which tools are explained by way of examples—such a book would be just the thing in Peter’s eyes. A book he could recommend to his company at all hierarchical levels. A book that expands the framework of inspi- ration and makes people want to learn more about design thinking. He would also like to know which design criteria will be needed in the future, in particular for the development of digital products and services.

“Who is Lilly?”

Lilly, 28 years old, is currently working as a design thinking and startup coach at Singapore University of Technology & Design (SUTD). Theinstitute is one of the pioneers in design thinking and entrepreneurship for technology-oriented companies in the Asian region. Lilly organizes workshops and courses that combine design thinking and leanstartup. She teaches Design Thinking and coaches student teamsin their projects. In tandem with that, she is working on her doctoralthesis—in cooperation with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—in the area of System Design Management on the subject of“Design of Powerful Business Ecosystems in a Digitized World.”

To divide participants into groups, Lilly uses the HBDI® (Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument) model in her design thinking courses. Productive groups of four to five are formed this way, each one of which works on one problem statement. She has discovered that it is vitally important in each group to unite all modes of thinking described in the brain model. Lilly’s own preferred style of thinking is clearly located in her right half of the brain. She is experimental, creative, and likes to surround herself with other people.

Lilly studied Enterprise Management at the Zhejiang University School of Management. For her master’s degree, she spent a year at the École des Ponts ParisTech. As part of the ME310 program and in collaboration with Stanford University, she worked on a project there with THALES as an industrial partner, which is how she became familiar with design thinking. During this project, she visited Stanford three times. She liked the ME310 project so much that she decided to attend the University of Technology & Design in Singapore. There, Lilly became known among faculty for her extravagant flip-flops. SUTD students were less enthusiastic about them.

More about Lilly: What is her background experience?

Lilly has great in-depth theoretical knowledge of various methods and approaches and is able to apply them practically with her teams of students. She is good at coaching these teams but lacks understanding of actual practice. Lilly offers design thinking workshops at the Center of Entrepreneurship at Singapore University of Technology & Design. Frequently, people from industrial enterprises who want to learn more in terms of their innovation capability or better understand the topic of “intrapreneurship” take part in these workshops. Lilly lives in Singapore and shares an apartment with her friend Jonny, whom she met during her year in France. Jonny is an expat who works for a major French bank in Singapore. At first, Jonny thought Lilly’s flip-flops were somewhat freaky but, at this point, he likes that little splash of color on her.

To maximize success, Jonny sees great potential in user-centered design and his bank’s pronounced orientation toward customer interaction points. He is enormously interested in new technologies. The thought of what they might mean for banks fascinates and unsettles him at the same time. He follows events in the fintech sector very closely and has identified new potentials that might result from a systematic application of blockchain. He wonders whether such disruptive new technologies will change banks and their business models even more fundamentally than Uber changed the taxi sector or Airbnb the hotel industry—and, if so, when such changes will take place. The core question for Jonny is whether a time will come when banks as we know them will cease to exist altogether. Either way, banks need to become more customer-oriented and make better use of the opportunities that digitization offers than potential newcomers. Jonny is not afraid of losing his job as yet. But still, a start-up together with Lilly might be an exciting alternative. Jonny would like to see his bank apply design thinking and internalize a new mindset, but this is nothing but wishful thinking thus far.

Lilly and Jonny would also like to set up a consulting firm that applies design thinking to support enterprises with digital transformation. They are still looking for something unique that their start-up could offer in comparison to conventional consultancy firms. In particular, they would like to address cultural needs in their approach to consulting. Lilly has observed too many times how the European and American design thinking mindset failed in an Asian context. She wants to integrate local particularities in her design thinking approach: the attitude of an anthropologist, the acceptance of copying competitors, and the penchant for marketing services more quickly, instead of observing the market for a long time. Something else makes them hesitant to implement their plan: They are bit risk averse because next year, once Lilly has completed her doctoral thesis, they want to get married and raise a family. Lilly wants three children.

In her free time, Lilly is active and creative. She often meets with like-minded people she knows from the SkillsFuture program, which is a national program that provides Singaporeans the possibility to develop their fullest potential throughout life, regardless of their starting points; or from events such as “Innovation by Design,” which was funded by the DesignSingapore Council. They develop concepts for, among other things, adapting the space and the environment of the country to the needs of people. Lilly is especially intrigued by digital initiatives and hackathons that come into being through real-time data from sensors, social media, and anonymized motion profiles of mobile devices. Singapore is a pioneer that brings the design thinking mindset actively to the entire nation, not least with the “Infusing Design as a National Skill Set for Everyone” campaign.

Visualization of the persona

User profile of an experienced design thinker from the academic environment:

Pains:

- Lilly is uncertain whether she wants to begin a family or a start-up after she has finished her dissertation.

- Lilly would like to work as a professor in the area of design thinking and lean start-up in Southeast Asia, preferably in Singapore, but no such position exists there yet.

- She feels confident in design thinking both in theory and in her work with students, but she has a hard time establishing its importance for actual practice and convincing partners in the industry of its power.

- Working with colleagues from other departments is difficult, although design thinking could be combined well with other approaches.

- Lilly would like to exchange ideas with other design thinkers throughout the world in order to enlarge her network and make contact with industry partners, but has not yet found a platform to do so.

Gains:

- Lilly enjoys the possibilities offered by the intense contact with students she has as a coach. She can easily try out new ideas, and observing of her students has yielded many findings for her doctoral thesis.

- Lilly loves TED Talks and MOOCs (massive open online classes). She has already attended many courses and talks revolving around the topics of design thinking, creativity, and lean start-up, and has thus acquired a broad knowledge base. She would like to integrate new findings and methods in her courses.

- Lilly wants to bring her knowledge to a community and cultivate contact with other experts, to advance methods, publish, and do research together.

- Through the exchange with those involved in actual practice, Lilly can test and improve new ideas.

Jobs-to-be-done:

- Lilly understands design thinking in theory and is good at explaining the approach to students. But sometimes, she can’t think of good new examples and success stories from industry that could motivate the students and workshop participants to try out design thinking on their own.

- Lilly coaches students and start-ups, and organizes design thinking and lean start-up workshops. Her aim is to boost user centricity with all participants.

- Lilly enjoys trying out new things. She knows ethnographic methods and human-centered approaches from her studies. What has surprised her time and again is that the stereotypes of individual disciplines have an element of truth in them, yet interdisciplinary teams still achieve more exciting results.

- Lilly wants to meet new people and find ideas for her work and her start-up.

Use cases:

The book Lilly wants is one that contains many examples and ac tivities from actual practice instead of pure theory. An easy-to-use reference book with tips from experts that widens her inspiration framework and fires her desire for design thinking. A playbook that looks into the future and shows how design thinking will continue to develop. A book that she can recommend to her students as further reading material.

“Who is Marc?”

Marc, 27 years old, completed his MSc in Computer Science two years ago. He used his time at Stanford University to build out his network. He also attended a number of pop-up sessions at the d.school (Stanford University design school) on the theme of entrepreneurship and digital innovation. Marc met like-minded people there who voiced ideas just as crazy as his. Because Marc is somewhat introverted and does not just walk up and speak to people easily, he was grateful for the workshops at the d.school, which were accompanied by a facilitator. The facilitator created an atmosphere in which not only were ideas exchanged but one’s thought preferences were recognized, and teams were optimally put together. His group quickly recognized and appreciated Marc as “the innovator.” The other team members had knowledge of marketing and sales, finance and management control, and health care and mechanical engineering. The group was thrilled by Marc’s idea of stirring up the health care and medtech industry through the use of distributed ledger technology. Marc made quite an impression with words like bitcoin, Zcash, Ethereum, Ripple, Hyperledger Fabric, Corda, and Sawtooth. He waxed enthusiastic about frameworks such as ERIS being miracle weapons to tame the smart-contract dragons. Moreover, Marc had already been involved in two start-ups. For the makers and shakers of two Web analytics firms, he had written code during a summer internship. The group quickly realized that they wanted to found a start-up, knowing very well that Marc’s technological affinity for blockchain, together with their business idea, would not yet make a profitable business. Processes and in particular business ecosystems must be designed to initiate a revolution.

More about Marc: What is his background experience?

Marc grew up with mobile communication. As a digital native, he pursues a technology-based lifestyle, as we have already learned. On the level of popular sociology, he is a typical representative of generation Y (why). It is important to him that he do something meaningful with his skills. He wants to work on a team and get recognition. It would be best that no one tell him what to do when it comes to his special field of blockchain.

Marc grew up in Detroit. His parents were middle class. Both of them had made careers in major automotive companies. Hence Marc witnessed how an entire industry can lose its luster bit by bit. The subprime and financial crisis showed him that, from one day to the next, it can become impossible to pay the mortgage for the big mansion in the Detroit suburbs. Marc learned early on how to deal with uncertainties. He internalized how to “dance” with uncertainty and how to weigh options. For him, design thinking and the associated mindset are a natural attitude. Questioning the things that exist and finding new solutions for problems have always been something obvious to him. He owed the privilege of studying at Stanford to a scholarship. Besides the option of founding a start-up with his team from the d.school, he has received job offers at the campus job fair from Spotify and Facebook involving artificial intelligence. Marc likes both companies because they promise he’d be master over his own time and be able to work autonomously.

In his leisure time, Marc is a big baseball fan. His favorite team is the Detroit Tigers.

Coming home from the job fair in question, Marc met Linda, a Brazilian beauty who works as a nurse at the health center of his university. Marc was so taken by reading on his smartphone about the concept of Everledger that he had stepped onto the bicycle lane. Linda was just able to brake in time, but they both got quite a fright from the encounter. Marc was a bit embarrassed, but then he dared ask Linda if she wanted to network with him on Facebook. Marc is very proud of this. Now they swap emoticons via Whatsapp nearly every hour. Marc usually sends little diamonds—not as a digital assets but as virtual tokens of affection to his lovely Linda. But he was also fascinated by the fact that diamonds as digital assets change owners through a private blockchain.

Visualization of the team

User profiles of a typical start-up team:

Pains:

- For Marc, his team doesn’t learn quickly enough. He wants to conduct simple experiments and devel-

- op prototypes in the service environment more rapidly.

- Marc pursues a lean approach for his start-up and has noticed how important it is to be honest with oneself and that the biggest risks should be tested first.

- The dynamics of the market and the technology are so great that even things that have already been tested ought to be questioned again and again.

- Marc always sees new options in the business ecosystem. It is sometimes hard for him to design a complex ecosystem and to shape the business models for the actors in the system.

Gains:

- Marc is enthusiastic about his subject and his team. He enjoys the energizing atmosphere and meaningful work.

- Marc uses design thinking for innovation exchange and combines it with new elements.

- Marc loves the possibilities of digital business models and knows that the whole world is in upheaval, offering start-ups huge opportunities.

- At this point, Marc has come to love interviews and tests with real users. He has learned to ask the right questions and looks forward to the new findings that are spewed forth at a rapid pace.

Jobs-to-be-done:

- Marc wants a book that gives leeway to his natural talent for questioning what exists, presents him with new tools, and shows him how they’re applied.

- He wants to know how he can transform his knowledge of information technologies into meaningful solutions. It’s vital to him that he find a scalable solution for his blockchain idea quickly and that an innovative business model makes the enterprise viable in the medium term.

- He wishes to work in an environment in which the concept of “teams of teams” is a lived reality, and would like to get suggestions for it.

- With the aid of design thinking, Marc wants to establish a common language and mindset. The dynamics, complexity, and uncertainty are rising. Marc can deal with the situation pretty well, but he has noted that his team is not so good at it.

- Particularly in the blockchain environment, technologicalvdevelopment is proceeding quite rapidly. The team must learnvfrom experiments speedily and develop both the market andvcustomers.

Use cases:

Marc would like a book that helps his team adopt the design thinking mindset more speedily and learn faster. The book should contain suggestions and tips, both for experienced design thinkers and for people who are dealing with the mindset for the first time.

In addition, Marc would like to get suggestions on how to develop his digital business ecosystem and how to maintain strategic agility even in the growth phase.

EXPERT TIP

Create a persona

How do we proceed when creating a persona?

There are different ways of creating personas. It is important to imagine the typical user as a “real person.” People have experience, a life career, preferences, and private and professional interests. The primary goal is to find out what their true needs are. Frequently, potential users are sketched out in an initial iteration, which is based on the knowledge of the participants. It must then be verified that a user who has been sketched out like this actually exists in the real world. Interviews and observations often show that potential users have different needs and preferences than those originally assumed. Without exploring these deeper insights, we never would have found out that Peter likes red underpants and Lilly has a tic with flip-flops. In many workshops, so-called canvas models are used in the context of strategy work and the generation of business models and business ecosystems associated with it. We developed a “user profile canvas” for our workshops that helps in having the key questions at hand and, based upon them, in creating a persona expeditiously. To promote the creativity of participants and encourage out-of-the-box thinking, it is useful to cut the canvas apart and glue it onto a huge poster. On this poster, the persona can be drawn in full size. In so doing, it is worthwhile to improve the persona iteratively, refining it and digging deeper step by step.

It always makes sense to ask for the “why” in order to get to the actual problem. We try to find out about real situations and real events so as to find stories and document them. Photos, images, quotes, stories, etc., help to make the persona come alive. In general, work with the persona concept is reminiscent of the procedure applied by so-called profilers (case analysts) in American detective TV series. Profilers are on the hunt for the perpetrators. They solve murders and reconstruct the course of events. They work by describing relevant personality and character traits in order to draw conclusions from behavior.

We recommend taking the time to create a persona yourself. The intensity and closeness are important for building up empathy with the potential user. If time is short, standard personas can be used. You must be cautious when it comes to personas with brief descriptions. The example of the “persona twins” shows why. Although the core elements are the same, the potential users couldn’t be more different. This is why it really makes sense to dig one level deeper to understand the needs in greater detail. We get greater insights, and that makes things even more intriguing.

USER PROFILE CANVAS

EXPERT TIP

Empathy map

How do we build up empathy with a potential user?

The initial draft of a persona is quickly done. Although just an outline exists, it can be quite helpful and eye-opening. A brainstorming on the team can yield initial insights and contribute to a better understanding; it is absolutely necessary, though, that it be underpinned with real people, observations, and interviews. In a first step, the user must be defined and found. Ideally, we’ll go outside right at the beginning and meet a potential user. We observe him, listen to him, and build up empathy. The insights are well documented, in the best case using photos and videos. If you take pictures, it is important to ask permission beforehand, because not everybody likes to be photographed or filmed! A so-called empathy card can be used here that addresses the following areas: hearing, thinking and feeling, seeing, speaking and doing, frustration, and desire. We also suggest speaking to experts who know the persona well and, of course, being active yourself and doing what the user is doing.

The credo is: “Walk in the shoes of a potential user!”

Especially when we think we know the products or the situation, we attempt to approach a situation like a beginner—curious and without previous knowledge. Consciously and with all our senses, we go through the experience the user is going through!

After this “adventure,” it is useful to define hypotheses on the team, then test them with a potential user or by using existing data, then confirm, discard, or adapt them. The picture of the persona becomes clearer and more solid with each iteration.

EXPERT TIP

Review the persona

To obtain initial knowledge on the user, another tool that helps is the AEIOU method. AEIOU helps us to capture all the events in our environment.

The task is clear. Get out of the design thinking rooms and speak to potential users, walk in their shoes, do what they do.

The AEIOU questions help to put some structure into the observations. Especially with inexperienced groups, it is easier this way to ensure an efficient briefing on the task at hand.

Depending on the situation, it is useful to adapt the questions individually to the respective observations. The AEIOU catalog of questions and the associated instructions help participants establish contact with initial potential users. Experience has taught us that it helps the groups if a design thinking facilitator or somebody with needfinding experience accompanies first contact of potential users. We all are pretty inhibited when it comes to addressing strangers, observing them, and asking them about their needs. Once the first hurdle has been cleared, some participants and groups develop into true needfinding experts. Chapter 1.4 will deal in greater detail with needfinding and the creation of question maps.

AEIOU is broken down into five categories.

Consider how each of the users behaves in the real world and the digital world.

Activities | What happens? What are the people doing? What is their task? What activities do they carry out? What happens before and after? |

Environment | What does the environment look like? What is the nature and function of the space? |

Interaction | How do the systems interact with one another? Are there any interfaces? How do the users interact among one another? What constitutes the operation? |

Objects | What objects and devices are used? Who uses the objects and in which environment? |

User | Who are the users? What role do the users play? Who influences them? |

EXPERT TIP

Hook framework

How can we use people’s habits for our market success?

The hook framework (Alex Cowan) is based on the idea that a digital service or a product can become a habit for a user. The hook canvas is based on four main components: trigger for an action, activity, reward, and investment. For the potential user, there are two triggers for his actions: triggers from the external environment (e.g., a notification from Tinder that you received a “Super Like”) or internal triggers for an action (e.g., visiting the Facebook app when you feel lonely).

The action describes the minimum interaction of your service or your product with a potential user. As a good designer, you want to design an action to be as simple and fast as possible for the user. Reward is the key emotional element for the user. Depending on the configuration of the action, the user can be given a lot more than the satisfaction of the initial need. Think of positive reviews and feedback through a comment or article. You just wanted to share the information, but you get back far more due to the reputation of the community.

The question remains as to what the user invests in order to get himself back in the loop and to trigger an internal or external action. For example, he actively follows a Twitter feed or writes a notification that a certain product or service is available again.

EXPERT TIP

Jobs-to-be-done framework

What is the actual task of a product?

The jobs-to-be-done framework became widely known through the milkshake example. The problem statement looks familiar to us: How can the sales of milkshakes be increased by 15%? With a conventional mindset, you would look at the properties of the product and then consider whether a different topping, another flavor, or a different cup size might solve the problem. Through a customer survey, you find out that the new properties are popular. However, in the end, only incremental innovations are realized, and the result has only been marginally improved. The jobs-to-be-done framework focuses instead on a change of behavior and on customer needs. In the case of the milkshake, it was found this way that two types of customers buy milkshakes in a fast food restaurant. The point of departure was: Why do customers buy a product? To put it differently: What product would they buy instead of the well-known milkshake?

The result:

The first type of customer comes in the morning, commutes to work by car, and buys a milkshake as a substitute for breakfast and as a diversion while driving. Coffee doesn’t work because it is first too hot and then too cold. It is also liquid and can spill easily. The ideal milkshake is large, nutritious, and thick. So the jobs-to-be-done of the milkshake are therefore a breakfast substitute and a pleasant diversion while driving to work.

The second type of customer comes in the afternoon, usually, a mother with a child. The child wants something to eat in the fast food restaurant and is whining. The mother wants to get something healthy for the child and buys a milkshake. The milkshake should be small, thin, and liquid, so the child can drink it quickly, and it should be low in calories. The milkshake’s jobs-to-be-done are to satisfy the child and make the mother feel good. In principle, for any product, whether digital or physical, you can ask: Why would a customer buy my product or service?

Innovations like those designed by Adobe Photoshop and Instagram are good examples of jobs-to-be-done in the digital environment. Both solutions aim at making photographs look like those taken by pros. Photo- shop offers easy professional editing of pictures through an app. Instagram realized early on that pictures can be easily edited and shared via social media.

HOW MIGHT WE...develop a persona?

Because human beings always take center stage in design thinking and the persona to be created is very important, we sketched out the approach once more by way of example. When teams are tasked with developing “empathy” with a user over a certain period of time, or when they first apply design thinking, it is useful to specify a structure and the steps to be taken. Depending on the situation, we recommend using the tools just described (AEIOU, jobs-to-be-done framework, hook canvas, user profile canvas) or integrating and using other methods and documents into the steps listed here. To help you better understand this process, the Playbook is interspersed with various “How might we . . .” procedures.

Find the user

Questions

Who are the users?

How many are there?

What do they do?

Methods

Quantitative collection of data, AEIOU method

Building up a hypothesis

Question

What are the differences between the users?

Methods

Description of the groups ofsimilar users/segmentations

Confirmations

Question

Is there any data or evidence that confirms the hypothesis?

Methods

Quantitative collection of data, empathy map

Finding patterns

Question

Are the initial descriptions of the groups still correct? Are there other groups that might be important?

Methods

Categorization, applying the jobs-to-be-done framework

Creating personas

Questions

How can the persona be described?

Methods

Categorization,

persona

Define situations

Question

What use cases does the persona have?

What is the situation?

Methods

Searching for situations and needs

User profile canvas/customer profile

Customer journey

Validation

Questions

Do you know such a person?

Methods

Interviews with people who know the personas

Reading and commenting on the persona description

Dissemination of knowledge

Question

How can we present the personas and share them with other team members, the enterprise, or stakeholders?

Methods

Posters, meetings, e-mails, campaigns, events, videos, photos

Creating scenarios

Questions

In a given situation and with a given objective: What happens when the persona uses the technology?

Methods

Narrative scenario—storytelling, descriptions of situations, and stories in order to create scenarios

Application of hook canvas

Continuous further development

Questions

Is there any new information? Does the persona have to be newly described?

Methods

Usability test, continuous revision of the persona

EXPERT TIP

Future user

How do we map the user of the future?

Especially in radical innovation projects, the time horizon is often far longer. It may take 10 years before a product is launched on the market, for example. If its target group is 30 to 40 years old, this means that these users now are 20 to 30 years old.

The future user method attempts to extrapolate these users’ future personas (see “Playbook for Strategic Foresight and Innovation”). It expands the classic persona by analyzing today’s persona and its development over the last few years. In addition, the future target group is interviewed at their present age. Subsequently, the mindset, motivation, lifestyle, etc. are extrapolated to get a better idea of the future user.

The method is easy to apply. It is best to start with the profile of the current user and underpin it with facts, market analyses, online surveys, personal interviews, and so forth. When developing the persona, changes in values, lifestyle, use of technologies/media, product habits, and the like, must be borne in mind.

KEY LEARNINGS

Working with personas

- Use real people with real names and real properties.

- Be specific in terms of age and marital status. Get demographic information from the Internet.

- Draw the persona, in life-size, if possible.

- Add visualizations to the persona. Use clip outs from magazines for accessories (e.g. watch, car, jewelry).

- Identify and describe use cases in which they would use the potential product or services.

- Put the potential user in the context of the idea, his team, and the application.

- List pains and gains of the persona.

- Capture the customer tasks (jobs-to-be-done) that the product or service supports.

- Describe the experience that is particularly critical. Build a prototype that makes it possible to find out what is really critical.

- In so doing, try to take the persona’s habits into account.

- Try out tools for the definition of the content (e.g., user canvas and customer profile, hook canvas, future user, etc).

1.2 Why is process awareness key?

An important factor of success in design thinking is to know where you stand in the process. For Lilly, Peter, and even Marc, the transition from a divergent to a convergent phase is a special challenge:

At what point in time have we gathered sufficient information, and how many ideas are necessary before we begin to transform the cavalcade of ideas into possible solutions?

Alongside the current level of development, the tools must be constantly kept in mind in design thinking. Which of them are the most effective in the current situation? There are generally two mental states in the “hunt for the next big opportunity”: Either we develop many new ideas (i.e., we “diverge,”) or we focus on and limit ourselves to individual needs, functionalities, or potential solutions (i.e., we “converge”). This is usually depicted in the shape of a double diamond.

For Lilly, it is a little easier to meet this challenge, because she knows how long her design thinking course at the university lasts, and she can control, as early as with the definition of the design challenge, how open or restrictive the question should be (i.e., how broad the creative framework for the participants is to be). With regard to real problem statements, things are somewhat different. Normally, we force ourselves at the beginning to leave our comfort zone and define the creative framework broader than we actually wish to. In the divergent phase, the number of ideas is infinite, so to speak. The tricky part here is to wrap up this phase at the right time and focus on the most important functionalities that ultimately lead to an optimal user solution. Of course, there are many examples of all sorts of ideas being launched on the market, and chance contributes to success— well-known examples include a number of services offered by Twitter. But chance does not often work this way; hence, in the process, converging is decisive for success.

Steve Jobs was a master when it came to managing the “groan zone” optimally. He had the right instinct to choose the time for a change of mindset and for leaving the divergent phase. This way, he led his teams to brilliant solutions. At Apple, Bud Tribble established the term “reality distortion field,” standing for Steve Jobs’s ability to master the mental leap. The term stems from an episode of the original Star Trek series, “The Menagerie,” in which aliens create their own world by means of their thoughts.

EXPERT TIP

Optimal point in time to change the mindset

One good influencer that helps us change our mindset is a limited period of time. If the final deadline for an innovation project is pushed forward or the first prototype is expected earlier than scheduled, the mindset must be automatically changed as well. In addition, it is advisable to lay down the functionalities and characteristics in an early phase of the design thinking process. During the transition to the convergent phase, we take them up again and attempt to match them to a great number of varying ideas. This selection makes it possible to eliminate some ideas at this stage. It can be useful for consolidating or combining ideas into logical clusters. But, even then, we won’t be spared from selecting and focusing in the end. It is helpful during this phase to present the remaining ideas to other groups and participants. Then Post-its can be distributed, and the community can decide which is the best idea. If we only involve our own group, the decision is often not objective enough because we always risk falling in love with a certain idea. It’s up to you how ideas that have not entered the convergent phase ought to be dealt with. Some facilitators encourage participants to throw the ideas written on the Post-its on the ground, while others keep the ideas as a knowledge reservoir until the end of the project.

What does the design thinking micro cycle look like?

Before we deal with the process in greater depth, we need to clarify the various design thinking processes, which basically all pursue the same goal but use different terms. Basically, there’s a problem statement at the beginning and a solution at the end, and the solution is reached in an iterative procedure. The focus is decidedly on the human being, so design thinking is often referred to as Human-Centered-Design. Most people who have already grappled with design thinking know the process. Nonetheless, we decided to address briefly the phases in the micro cycle and the macro cycle as well as the core idea of each phase. Lilly would probably identify with the six-step depiction used at the HPI (Hasso Plattner Institute) that presents, as most universities do, the process of design thinking that follows. Subsequently, we will discuss the macro cycle.

At some universities, the process was simplified still more. In Japan, for instance, at the chair for Global Information Technology at Kanazawa Technical College, they work with four instead of six phases: Empathy—Analysis—Prototype—Co-Creation. D.school consolidates the process steps of “Understand” and “Observe” into “Develop empathy.”

The IDEO design and innovation agency had originally defined five simple steps in the micro cycle in order to get to new ideas through iterations. In addition, they put a strong focus on implementation, because the best ideas are ultimately of no use if we haven’t established them on the market as a successful innovation:

UNDERSTAND the task, the market, the clients, the technology, the limiting conditions, restrictions, and optimization criteria.

OBSERVE and ANALYZE the behavior of real people in real situations and in relation to the specific task.

VISUALIZE the first solution drafts (3D, simulation, prototypes, graphics, drawings, etc.).

EVALUATE and OPTIMIZE the prototypes in a fast succession of continuous repetitions.

IMPLEMENT the new concept in reality (the most time-consuming phase).

Anybody working at an actual business ought to know iterative procedures in a different context, such as from software development (ISO Standard 13407 or Scrum). In this case, the user suitability of software is ensured by an iterative process or improved incrementally through sprints.

In ISO 13407, the following phases are spoken of:

Planning, process—Analysis, use context—Specifications, user requirements—Prototype (draft of design variants)—Evaluation (evaluation of solutions and requirements)

With Scrum, the individual iterations are called sprints. One sprint takes 1 to 4 weeks. So-called product backlogs serve as inputs into the sprints. They are then prioritized and processed in the sprints (sprint backlogs). The requirements are documented in the form of user stories in the product backlog. A ready-to- deliver product that has already been tested with the user during the sprint is what should exist at the end of each sprint. In addition, the process itself is reviewed and continually improved in the Retrospective.

At most companies, a micro design thinking process is broken down into three to seven phases, often based on the steps of IDEO, d.school, and the HPI. The Swiss ICT company Swisscom has designed a simplified micro cycle that allows for integrating the mindset quickly into the organization.

The phases are: Hear—Create—Deliver.

| Phase | Description | Basic tools |

|---|---|---|

| Hear | Understand the project Understand the customer problem/need Procure information, internal and external Gather experience directly from the customer | Design challenge Customer interview |

| Create | Transform what was learned into potential solutions Generate multiple solutions and possibilities Define solution features | Core beliefs Target customer experience chain |

| Deliver | Concretize ideas Create and test prototypes Verify, expedite, or reject ideas Gain insights and learn from them | Need, Approach, Benefit, Competition (NABC) Prototyping plan Self-validation |

EXPERT TIP

The design thinking micro cycle

DESCRIPTION OF THE INDIVIDUAL PHASES OF THE MICRO CYCLE

UNDERSTAND:

This phase was already touched upon in Chapter 1.1. Our starting point was not a goal to be achieved but a persona that has needs or is facing the challenge of having to solve a problem. Once the problem has been recognized, the problem statement must be defined at the right level of comfort. With two types of questions, we can either expand (WHY?) or narrow down (HOW?) the creative framework. The principle can be illustrated most easily on the basis of the need to educate ourselves further:

Alongside the problem statement, it is important to understand the overall context. Answering the six WH questions (who, why, what, when, where, how) yields fundamental insights:

- Who is the target group (size, type, characteristics)?

- Why does the user think he needs a solution?

- What does the user propose as a solution?

- When and for how long is the result needed (time span of the project or life cycle of the product)?

- Where is the result going to be used (environment, media, location, country)?

- How is the solution implemented (skills, budget, business model, go-to market)?

More on this in Chapters 1.4 and 1.5.

OBSERVE:

We have already initially dealt with the Observe phase to some extent. We tried to be experts and better understand the needs of our readers. We took a closer look at people from three different environments who apply design thinking and observed the groups of persons at work. To do so, we took advantage of various opportunities: at the HPI in Potsdam, at the d.school in Stanford, interacting with coaches from the ME310; in workshops with the DTP Community at Startup Challenges; in internal workshops at companies as well as in co-creation workshops with the objective of inspiring customers for digitization; and so on. It is always important to document and visualize these findings so they can be shared with others at a later time. So far, most of those involved in design thinking focus on the qualitative method of observation. Documentation is done by means of idea boards, vision boards, daily story based on photos, mind maps, mood pictures, and photos of life situations and people. All this is important information we can use to create and revise personas and to build up empathy for the user, as will be described in more detail in Chapter 1.5.

DEFINE POINT OF VIEW:

For the point of view, the important thing is to draw upon, interpret, and weight all the findings. The facilitator is urged to encourage all members of a group to talk about their experience. The goal is to establish a common knowledge base. This is done best by telling stories that have been experienced, showing pictures and describing the reactions and emotions of people. Again, the aim is to develop further or revise the personas in question. We will discuss this step in detail in Chapter 1.6.

IDEATE:

In the phase of Ideation, we can apply various methods and approaches that heighten creativity. Irrespective of this, we normally use brainstorming or the creation of sketches in this phase. The goal is to develop as many different concepts as possible and visualize them. We present a number of techniques for this in Chapter 1.7. The phase of Ideation is closely associated with the subsequent phases in which prototypes are built and tested. The next Expert Tip will give depth to this approach. In this phase, our primary goal is the step-by-step increase of creativity per iteration. Depending on the problem statement, a general brainstorming session on possible ideas can be held at the onset. Presenting individual tasks in a targeted manner for the brainstorming session has proven successful; this way, creativity and thus the entire diverging phase can be controlled. Examples include a brainstorming session on the critical functions, benchmarking with other industries or situations, and a dark horse that deliberately omits the actual situation or combines the best and worst ideas. A funky prototype that simply ignores all limiting factors can also generate ideas. We will specifically address the matter in the depiction of the macro cycle.

PROTOTYPE:

In the previous phase, we already pointed out the next steps of “Build prototype” and “Test prototype” because they are always connected to ideation. Chapter 1.9 will show what makes up a prototype.

At any rate, we should make our ideas tangible as early as possible and test them with potential users. This way, we receive important feedback for the improvement of ideas and prototypes. The motto of the options for action is simple: Love it, change it, or leave it.

TEST:

This phase comes after each developed prototype and/or after each drafted sketch. We can do the testing with colleagues, but the interaction with potential users is what’s really intriguing. Alongside traditional testing, it is possible today to use digital solutions for testing. Prototypes or individual functionalities can be tested quickly and with a large number of users. We will present these possibilities in Chapter 1.10. We receive mostly qualitative feedback from this phase. We should learn from these ideas and develop them further until we love our idea. Otherwise: discard or change.

REFLECT:

Before starting a new cycle of the iterative process, it is worthwhile to reflect upon the chosen direction. Reflection is best triggered by questioning whether the ideas and test results comply with claims of being socially acceptable and resource-efficient. With agile methods such as Scrum, the Reflect phase wraps up the process in retrospection. The process and the last iteration are reviewed, and a discussion follows on what went well and what should be improved. The questions can be played through in a “I like—I wish” feedback cycle, or feedback can be obtained in a structured way using a feedback capture grid. Naturally, we also use the Reflection phase to consolidate the findings if this hasn’t yet occurred in the Test phase.

We update the personas and, if necessary, other documents on the basis of these findings. In general, reflecting helps to explore new possibilities that might lead to better solutions or improve the processas a whole.

HOW MIGHT WE... run through the design thinking macro cycle?

In the micro cycle, we go through the phases of Understand, Observe, Define point of view, Find ideas, Develop prototype, and Test prototype. They must be seen as a unit. In the divergent phase, the number of ideas we gather through various creativity techniques increases constantly. Some of these ideas we want to make tangible in the form of prototypes and test with a potential user. The respective creativity methods and tools are used depending on the situation. The journey toward the ultimate solution is not certain at the onset.

The issue in the macro cycle is to understand the problem and concretize a vision of the solution. To do this, many iterations of the micro cycle are run through. The initial steps in the macro cycle are of a divergent character (steps 1-5 in the figure). In the case of simple problems or if the team possesses comprehensive knowledge of the market and the problem, the transition to the groan zone (step 6) can be pretty fast. Transition to the groan zone can be effected from any one of the five divergent steps. The sequence of ideas to be elaborated can and must be adapted to the situation and the project. The suggested sequence has been successfully applied in many projects, though. The vision of the solution or idea is concretized in the form of a vision prototype and tested with different users. If the vision gets generally positive feedback, it is concretized in the next iteration (step 7).

The hunt for the next big market opportunity often follows these steps:

(1) Initial ideas are worked out in a brainstorming session

An initial brainstorming session about potential ideas and solutions helps the group to place all sorts of ideas and get them off their collective chest. Frequently, the levels of knowledge of the individual team members in terms of the problem statement and a possible solution spectrum are quite different. An initial brainstorming session helps in approaching the task and learning how the others in the group think.

Instruction: Give the group 20 minutes for a brainstorming session. The issue here is quantity, not quality. Every idea is written on a Post it. When writing or sketching on the Post-it, the idea is expressed aloud; afterward, the note is stuck to a pin board.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- Which ideas come to mind spontaneously?

- Which solution approaches are pursued by the others?

- What can we do differently?

- Do we all have the same understanding of the problem statement?

(2) Develop critical functionalities that are essential for the user

This step can be crucial for the solution. The facilitator has the task of motivating the groups so they identify exactly these “important things” and prepare a ranking in the context of a critical user.

Instruction: Give the group one to two hours—depending on the problem statement—to draft, build, and

test 10 to 20 critical functions.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- Which functionalities are mandatory?

- What experience is absolutely necessary for the user?

- What is the relationship between the function and the experience?

(3) Find benchmarks from other industries and experiences

This step is a very good tool when teams are not able to tear themselves away from an original solution concept.

Benchmarking helps participants think outside the box and adapt ideas from these areas for the solution of the problem. The facilitator broadens the creative framework by motivating the groups to hold the brainstorming session, taking into account a certain industry/sector or a particular experience. You can proceed in two steps, for instance: (a) brainstorming of ideas relating to the problem, and (b) brainstorming of industries and/or experiences. Subsequently, the three best ideas from each step are identified. Based on the combination of these, the facilitator invites the participants to develop two or three ideas further, build them physically, and test them with the user.

Instruction: Give the group 30 minutes for a brainstorming session, 30 minutes for finding benchmarks, and 30 minutes for clustering and combining ideas. Depending on the task, the group is given enough time to build two to three prototypes.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- Which successful concepts and experiences can be applied to the problem?

- Which experiences can illuminate the problem from another perspective?

- What is the relation between the problem and other experiences?

(4) Heighten creativity and find the dark horse among the ideas

This step helps many teams to boost creativity further—not least because, for the dark horse, borders are lifted, which might have limited us in the previous steps. The facilitator motivates the groups to strive for maximum success and thus develop a radical idea. Now the time has come for the teams to heighten creativity and accept the maximum risk. One possibility for the creation of a dark horse is to omit essential elements of a given situation, such as, “How would you design an IT service desk without IT problems?” “What does a windshield wiper look like without a windshield?” or “What would a cemetery look like if no one died?” The main point is to leave the comfort zone and “do it in any case,” no matter what will occur.

Instruction: Give the group 50 minutes to build a dark horse and enough time for building a corresponding prototype depending on the task.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- Which radical possibilities have not been considered thus far?

- Which experiences lie outside anything imaginable?

- Are there products and services that would expand value creation?

(5) Implementation of a funky prototype to give free rein to creativity

In many cases, you have to go one step further because the team has not come up with disruptive ideas so far. The building of a funky prototype cranks up creativity one more notch. It encourages the teams to maximize the learning success and at the same time minimize costs in terms of time and attention. The goal is to develop solutions that mainly focus on the benefit. Potential costs and any budget restrictions are completely removed.

Instruction: Give the group an hour to build a funky prototype.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- What crazy ideas are super cool?

- For which idea would you have to ask forgiveness in the end?

- What does an idea look like that is realized ad hoc and has not been planned?

(6) Determine the vision of the idea with the vision prototype

The groan zone is the transition from the convergent to the divergent phase. The phases can be changed at any time. Experienced facilitators and innovation champions recognize this point in time and lead their teams in a targeted way to the convergent phase. In the vision prototype, we make an initial combination of

- prior knowledge (caution is advisable here),

- best initial ideas,

- most important critical functionalities,

- new ideas of other industries and experience,

- initial user experience,

- intriguing insights (e.g., from the dark horse), and

- the simplest possible solution.

Instruction: Give the group about two hours (depending on the complexity of the problem) for building a vision prototype. It should then be tested with at least three potential users; the feedback is to be captured in detail. In the best-case scenario, these users are then involved in the subsequent concretization of the design thinking project. If so-called lead users are known in a field of innovation, they are perfect as references because they are often highly motivated to satisfy their needs.

Ask the group to answer the following key questions:

- Does the vision generate enough attention so a potential user absolutely wants to use this solution?

- Does the vision give sufficient leeway for a user’s dreams?

- Is the value offer of the vision convincing?

- What else would the users wish for in order to make the experience perfect?

(7) Concretize the vision step by step

In the following convergent phase, we want to focus on the concretization of the vision. The theme of this phase is the specific elaboration of the selected idea. It is iteratively improved and expanded. It is advisable here first to build and test the most important critical functionalities as integral parts of a functional prototype. With this prototype as a starting point, more elements are supplemented and finally the prototype is built. Different ideas can be tested in the convergent phase, and the best ones are integrated into the ultimate solution. Individual features or various combinations can be developed and tested, for instance. Once the prototype has a certain maturity, we can describe it in a “prototype vision canvas.” This way, we can formulate and compare various visions.

It is all about the iterative detailing and elaboration of the selected idea.

The maturity of the prototypes increases with every individual step.

A. Functional prototype

With respect to the functional prototype, it is important to concentrate on the critical variables and test them intensively with potential users. Critical functions must be created for critical experiences. Not all functionalities must be integrated at the onset. The crucial point is to ensure minimum functionality in order to test the prototype under real conditions. These prototypes are frequently referred to as “minimal viable product” (MVP). These MVPs serve as a foundation to build upon, and step by step a finished prototype emerges that combines several functions.

B. Finished prototype

The creation of a finished prototype is crucial for the interaction with the user, because only reality yields truth. Enough time must be scheduled for building a finished prototype, and the respective functionalities must be integrated.

C. Final prototype

The final prototype excels by the elegance of the thoughts invested in it as well as in its realization. Prototypes that are convincing with simple functionality are usually also successful when launched on the market. It is advisable to obtain as much support from suppliers and partners in any and every possible way. The use of standard components increases the likelihood of success and massively reduces development costs.

D. Implementation plan: How to bring it home

Not only the quality of the product or service is decisive, but also its implementation. Important things to know: Who might put obstacles in the way of the implementation process and try to influence decisions? The credo: Turn those affected into people who are involved and create a win-win situation for all parties. Chapter 3.4 describes what is important in the implementation process.

KEY LEARNINGS

Keeping a grip on the process

- Define a problem statement on the right level.

- Leave the comfort zone (as often as possible) if you want radical innovations to emerge.

- Develop awareness of the groan zone in the macro cycle, because it is decisive for the future success of the generated ideas.

- Create clarity on the team about whether the divergent or convergent mindset is currently at center stage.

- Use different methods in the divergent phase for brainstorming in order to heighten creativity (e.g., benchmarking, funky prototype, dark horse).

- Generate as many ideas as possible in the divergent phase by applying different creativity techniques.

- Always follow the sequence of “Design—Build—Test” in the micro cycle.

- Find the final prototype through converging and the respective iterations.

- Don’t develop emotional ties to prototypes and ideas. Discard bad ideas.

- What applies to all ideas: Love it, change it, or leave it!

1.3 How to get a good problem statement

At the beginning, Peter didn’t understand why it’s important to have a good problem definition in design thinking. After all, he wanted to find good solutions and not make the problems worse. During his first tentative steps as a facilitator for design thinking workshops, though, he quickly noticed, just how important the problem definition is. He realized there are three essential prerequisites for good solutions:

- The design thinking team must have understood the problem.

- The design challenge must be defined to allow for the development of useful solutions.

- The potential solution must fit the defined design space and design scope.

We break down problems into three types: simple (well-defined), poorly defined (ill-defined) and complex (wicked). For simple and clearly defined problems, there is one correct solution, but the solution strategy can follow different paths. Most problems we encounter in design thinking and in our daily work are ill-defined problems, however. They can be remedied with more than just one correct solution, and the search for such a solution can take place in quite different ways. From our experience, we nevertheless know that these problems can be rendered graspable and easily processed. Often it’s enough to reduce the creative framework or sometimes widen it a bit to get to the right level that allows new market opportunities to emerge.

Repeatedly asking “Why?” expands the creative framework; asking “How?” scales it down. In the Introduction, we briefly referred to the question of how we would tackle the issue of further training with design thinking. Designing a better can opener that everybody in the family likes using is another simple example of a design challenge.

To expand the problem statement, we pose the question of “Why?”. Quickly we realize that repeatedly asking why brings us to the limits of our comfort zone in no time at all, so that we are actually moving toward earth-shaking and difficult-to-solve problems, so-called wicked problems. In terms of the can opener, examples of such problems are:

- How can we stop hunger in the world?

- How can we prevent so much food from being thrown away?

To narrow down alternative solutions, it helps to ask “How?” With regard to the can opener:

- How can the can be opened with a rotating mechanism? or:

- How can the can be opened without any additional device?

Regarding wicked problems, the actual issue is often not obvious, so preliminary problem definitions are used. This leads to an understanding of the solution that changes the understanding of the problem again. So there are iterations already in the problem definition that can help interpret the understanding of the problem as well as of the solution. Only short-term or provisional solutions are largely found by way of this co-evolution, though. The use of linear and analytical problem-solving procedures quickly makes you hit your limits in terms of wicked problems: Because the problem is the search for the problem, you’re pulled every which way.

Fortunately, relevant tools for this were discovered in design thinking over the years, such as the question of “How might we . . .?” or a technique regarding “why” questions. Thus design thinking helps to make wicked problems graspable. If no solutions are found despite the use of design thinking due to the complexity of the problems, limited resources such as money and time are usually the reasons for the termination of the process. This is why we recommend devoting enough time and energy to work out the definition of a suitable problem definition.

To which types of problems can design thinking be applied?

Design thinking is suitable for all types of problem statements. Applications range from products and services to processes and individual functions, all the way to comprehensive customer experiences. But the goals people want to achieve with it differ. A product designer wants to satisfy customer needs, while an engineer is more interested in defining the specifications.

EXPERT TIP

Finding the design challenge

In her design thinking courses, Lilly often has difficulty finding good design challenges. If the design challenges come from industry partners, the creative framework is usually more or less set. In cases where the participants must identify problems on their own, things get more complex. The following options have proven quite useful for identifying problems and defining design challenges:

How might we improve the customer-experience chain of places and things that are visited or used daily?

Examples:

- How might we improve the online shopping experience of a shoe retailer?

- How might we improve the online booking portal for the car ferry from A to B?

- How might we improve customer satisfaction with the ticket app for public transport in Singapore?

Another possibility for getting to a design challenge is to change perspective. These questions help capture the design challenge:

- What if . . .?

- What might be possible?

- What would change behavior?

- What would be an offer if business ecosystems connected with each other?

- What is the impact of a promotion?

- What will happen afterward?

- Are there any opportunities where other people only see problems?

Another possibility is to take a closer look at an existing product or service (e.g., the customer experience chain when buying a music subscription). By asking questions and observing, we get hints for a design challenge:

- What does the music behavior of a user look like?

- How does the customer get information on new music offerings?

- How and where will the customer install the product or service?

- How does the customer use the product?

- How does the customer act when the product does not work as expected?

- How satisfied is the customer with the entire customer experience chain?

EXPERT TIP

Drawing up the design brief

The description of the design challenge is definitive. As we remarked, a good solution can only come about if the design thinking team has understood the problem.

The description of the challenge must be seen as a minimum requirement. Further details help to expedite the problem solving. The disadvantage here is that the degree of freedom in relation to the radicalism of a new solution is limited. The creation of a good design brief (short profile of the project) is already a small design thinking project in itself. Sometimes, we draw up the design brief for our users, sometimes for the design thinking team. We recommend you get different opinions—preferably on an interdisciplinary basis—about the problem and then agree, through iterations, on statements that really make up the problem.

The design brief contains various elements and can provide information on core questions:

Definition of design space and design scope:

- Which activities are to be supported and for whom?

- What do we want to learn about the user?

Description of already existing approaches to solving the problem:

- What already exists, and how can elements of it help with our own solution?

- What is missing in existing solutions?

Definition of the design principles:

- What are important hints for the team (e.g., at which point more creativity is demanded or that potential users should really try out a certain feature)?

- Are there any limitations, and which core functions are essential?

- Whom do we want to involve, and at what point in the design process?

Definition of scenarios that are associated with the solution:

- What does a desirable future and vision look like?

- Which scenarios are plausible and possible?

Definition of the next steps and milestones:

- By when should a solution have been worked out?

- Are there steering committee meetings from which we can get valuable feedback?

Information on potential implementation challenges:

- Who must be involved at an early stage?

- What is the culture like for dealing with radical solution proposals, and how great is its willingness to take risks?

A design brief is the translation of a problem into a structured task:

HOW MIGHT WE... start, although the problem is elusive?

In principle, the ideal starting point is where we leave the comfort zone. To find the right starting point based on a problem statement is not very easy. Often the team wonders whether the starting point is too narrow or too broad. In such a case, we recommend just starting. If the challenge is too narrowly conceived, the team will expand the problem in the first iteration. If the challenge is conceived too broadly, the team will narrow it down.

Do we want to improve the cap of a ball-point pen or do we want to solve the world’s water problem?

The procedure consists of three steps.

Step 1:

Who is the user in the context of the problem statement?

Define who the user really is and what his needs are.

Reflect on the created persona.

Step 2:

Apply the WH questions. Discuss the WHY, the WHAT, and the HOW.

Step 3:

Based on this, formulate your question.

As described, the “why” and the “how” questions can expand or narrow down the framework. A natural adjustment often takes place in a brainstorming session, especially if various methods are used in brainstorming, such as transforming and combining or even minimizing.

| Method | How can we solve our problem? | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimize | reduce it? | reduce an existing solution |

| Maximize | expand it? | expand an existing solution? |

| Transform | mentally transfer it to another area? | transfer a solution existing in another area to my problem? |

| Combine | combine it with other problems? | combine several existing solutions? |

| Modify/Adapt | modify it? | modify an existing solution? |

| Rearrange/Invert | change or invert its internal order? | change or invert the order of an existing |

| Substitute | substitute a partial problem? | substitute a part of an existing solution? |

Let’s take the example of a BIC ballpoint pen and the method of leaving out or reducing. For the BIC ballpoint pen, everything that was unnecessary was left out. All that was left in the end were three indispensable, essential parts: the refill, the holder, and a cap that also serves as a clip. An ingenious product that has remained unaltered for more than 50 years.

Is there even any room left for innovation?

The answer is: Yes! Perhaps you have already asked yourself before why the cap of the BIC ballpoint pen has a hole at the tip. The hole was not always there. It was designed to prevent small children from suffocating if they swallow the cap and it gets stuck in their windpipe. Sufficient air can still get through the little hole. This is why BIC pen caps have had holes for more than 24 years.

KEY LEARNINGS

Draw up the problem definition

- Question in the form of “Why?” and “How might we?” in order to grasp and understand the problem.

- Clarify what type of a problem it is: wicked, ill-defined, or well-defined. Adjust your approach accordingly.

- In the case of wicked problems, first find partial solutions for a partial problem. Proceed iteratively.

- Understand further partial aspects of the overall problem if it can’t be understood at once, and iteratively add more solution components.

- Draw up a structured design brief so that the team and the client have the same understanding of the starting point.

- Make use of different possibilities of finding the design challenge (e.g., investigation of the entire customer experience chain or a change of perspective).

- Begin with the first iteration even if the ideal starting area has not been found yet. This way, the problem can often be understood better.

1.4 How to discover user needs

Priya has a new innovation project. Rumors have it that the Internet and technology giant where Priya is working will embrace the theme of health for seniors—a theme and a segment about which Priya knows little and which, for her personally, is still pretty remote. Actually, Priya has little time for taking the needs of seniors into consideration alongside her numerous other projects. Her work environment teems with people in their mid-twenties; hardly anyone has yet crossed the threshold of 50 and can be classed even remotely in this segment. Her friends and acquaintances in Zurich are all between 30 and 40 years old, and her parents are still working full time and don’t feel they belong in the user group of retirees. Her grandparents, whom Priya could ask, have unfortunately passed away.

How can we carry out a needfinding when we actually have no time for it? Or better: How do we explain to the boss that we won’t come to work today?

Priya is aware that the personal contact with potential users—that is, people—is indispensable if you really want to live good design thinking.

Omitting the needfinding is not an option for Priya, because it would mean skipping over an entire phase of the design thinking process. Because the phases of understanding and observing as well as the synthesis (defining the point of view) cannot be strictly separated from one another, ignoring needfinding would mean omitting no fewer than three steps.

All these steps have an important feature in common: the direct contact with the users, the target group of people who will use an innovative product or our service regularly in the future.

It is an illusion to think that we are familiar with the lifestyles of all the people for which we develop innovations day after day. Let’s take a look at all the projects Lilly has gone through over the last four years as a needfinding expert: She would have had to be old, visually impaired, lesbian, a kindergartener, or even an illegal immigrant. Not to mention the project concerning a palliative care ward that inevitably would have catapulted Lilly into her deathbed. That certainly didn’t happen to Lilly. At least not at the time when her task was to innovate everyday life for these people in the final hours of life and the procedures at a palliative care ward.

It is important to reflect on ourselves and realize we don’t represent the people for whom we develop our innovation. If we do, in very exceptional cases, we must proceed with great caution when transferring our needs onto others.