An Introduction to SQL

Almost every web site nowadays, it seems, uses a database. Your objective, as a web developer, is to be able to design or build web sites that use a database. To do this, you must acquire an understanding of and the ability to use Structured Query Language (SQL), the language used to communicate with databases.

We'll start by introducing the SQL language and the major SQL statements that you’ll encounter as a web developer.

SQL Statement Overview

In the past, SQL has been criticized for having an inappropriate name. Structured Query Language lacks a proper structure, does more than just queries, and only barely qualifies as a programming language. You might think it fair criticism then, but let me make three comments:

Structure refers to the fact that SQL is about tables of data or, more specifically, tabular structures. A table of data has columns and rows. There are many instances where we’ll encounter an alternative that isn’t, strictly speaking, a table, but looks and acts like one. This tabular structure will be explained in Chapter 3.

While SQL includes many different types of statements, the main one is the

SELECTstatement, which performs a query against the database, to retrieve data. Querying data effectively is where the action is, the primary focus of the first eight chapters. Designing the database effectively is covered in the last three chapters.

The SQL language has been standardized. This is immensely important, because when you learn effective SQL, you can apply your skills in many different database environments. You can develop sites for your client or boss using any of today’s common database systems—whether proprietary or open source—because they all support SQL.

Those three concepts—tabular structures, effective querying, and SQL standards—are the secret to mastering SQL. We’ll see these concepts throughout the book.

Note: SQL or Sequel?

Before the real fun begins, let’s put to rest a question often asked by newcomers: how do you pronounce SQL?

Some people say the letters, “S-Q-L.” Some people pronounce it as a word, “sequel”. Either is correct. For example, the database system SQL Server (by Microsoft, originally by Sybase) is often pronounced “sequel server”. However, SQL, by itself—either the language in general or a given statement in that language—is usually pronounced as S-Q-L.

Throughout this book, therefore, SQL is pronounced as S-Q-L. Thus, you will read about an SQL statement and not a SQL statement.

We’ll begin our overview of SQL statements by looking at their components: keywords, identifiers, and constants.

Keywords, Identifiers, and Constants

Just as sentences are made up of words that can be nouns, verbs, and so on, an SQL statement is made up of words that are keywords, identifiers, and constants. Every word in an SQL statement is always one of these:

- Keywords

These are words defined in the SQL standard that we use to construct an SQL statement. Many keywords are mandatory, but most of them are optional.

- Identifiers

These are names that we give to database objects such as tables and columns.

- Constants

These are literals that represent fixed values.

Let’s look at an example:

SELECT name FROM teams WHERE id = 9Here is a perfectly respectable SQL statement. Let’s examine its keywords, identifiers, and constants:

SELECT,FROM, andWHEREare keywords.SELECTandFROMare mandatory, butWHEREis optional. We'll cover only the important keywords in SQL in this book. However, they’re all listed in Appendix D for your reference.

name,teams, andidare identifiers that refer to objects in the database.nameandidare column names, whileteamsis a table name.We’ll define both columns and tables later on in this chapter but, yes, they are exactly what you think they are.

The equals sign (

=) is an operator, a special type of keyword.

9is a numeric constant. Again, we'll look at constants later in the chapter.

So there you have it. Our sample SQL statement is made up of keywords, identifiers, and constants. Not so mysterious.

Clauses

In addition, we often speak of the clauses of an SQL statement. This book has entire chapters devoted to individual clauses. A clause is a portion of an SQL statement. The name of the clause corresponds to the SQL keyword that begins the clause. For example, let’s look at that simple SQL statement again:

SELECT nameFROM teamsWHERE id = 9The SELECT clause is:

SELECT nameThe FROM clause is:

FROM teamsThe WHERE clause is:

WHERE id = 9Tip: Coding Style

You’ll have noticed that, this time, the query is written with line breaks and indentation. Even though line breaks and extra white space are ignored in SQL—just as they are in HTML—readability is very important. Neatness counts, and becomes more pertinent with longer queries: the tidier your queries the more likely you are to spot errors. I’ll say more on coding style later.

Syntax

Each clause in an SQL statement has syntax rules for how it may be written. Syntax simply means how the clause is put together—what keywords, identifiers, and constants it consists of, and, more importantly, whether they are in the correct order, according to SQL’s grammar. For example, the SELECT clause must start with the keyword SELECT.

Note: Syntax and Semantics

In addition to syntax, semantics is another term sometimes used in discussing SQL statements. These terms simply mean the difference between what the SQL statement actually says versus what you intended it to say; syntax is what you said, semantics is what you meant.

The database system won’t run any SQL statement with a syntax error. To add insult to injury, the system can only tell you if your SQL statement has a syntax error; it doesn’t know what you actually meant.

To demonstrate the difference between syntax and semantics, suppose we were to rewrite the example from the previous section like so:

FROM teams WHERE id = 9 SELECT nameThis seems to makes some sense. The semantics are clear. However, the syntax is wrong. It’s an invalid SQL statement. More often, you’ll get syntactically correct queries that are semantically incorrect. Indeed, we’ll come across some of these as we go through the book and discuss how to correct them.

Up to this point, I’ve alluded to a couple of database object types: tables and columns. To reference database objects in SQL statements we use their identifiers, which are names that are assigned when the objects are first created. This leads naturally to the question of how those objects are created.

Before we answer that, let’s take a moment to introduce some new terminology. SQL statements can be divided into two types: DDL and DML.

- Data Definition Language (DDL)

DDL is used to manage database objects like tables and columns.

- Data Manipulation Language (DML)

DML is used to manage the data that resides in our tables and columns.

The terms DDL and DML are in common use, so if you run into them, remember that they’re just different types of SQL statements. The difference is merely a convenient way to distinguish between the types of SQL statements and their effect on the database. DDL changes the database structure, while DML changes only the data. Depending on the project, and your role as a developer, you may not have the authority or permission to write DDL statements. Often, the database already exists, so rather than change it, you can only manipulate the data in it using DML statements.

The next section looks at DDL SQL statements, and how database objects are created and managed.

Data Definition Language

In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.

--Douglas Adams

Where do database objects like tables and columns come from? They are created, modified, and finally removed from the database using DDL, the Data Definition Language part of SQL. Indeed those three tasks are accomplished using the CREATE, ALTER, and DROP SQL statements.

Tip: Trying Out Your SQL

It’s one thing to see an example of SQL syntax, and another to adapt it to your particular circumstance or project. Trying out your SQL statements is a great way to learn. If you have some previous SQL experience, you already know this (and might want to skip ahead to Chapter 2). If you are new to SQL, and want to experiment with the following DDL statements, keep in mind that you can always start over. What you CREATE, you can ALTER, or DROP, if necessary.

Appendix A explains how to set up a testing environment for five popular database systems—MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, DB2, and Oracle—and Appendix C contains a number of DDL scripts you can try running if you wish.

CREATE, ALTER, and DROP

Of the many DDL statements, CREATE, ALTER, and DROP are the three main ones that web developers need to be aware of. (The others are more advanced and beyond the scope of this book.) Even if you haven’t been granted the authority or permission to execute DDL statements on a given project, it helps to know the DDL to see how tables are structured and interconnected.

The CREATE Statement

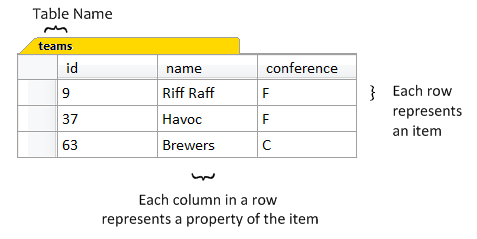

Earlier on, I suggested that a tabular structure is one of the main concepts you need to understand when learning SQL. It’s actually quite simple, and a table of data looks exactly like you would intuitively expect it to—it has columns and rows. Each table contains information concerning a set of items. Each row in a table represents a single item. Each column represents one piece of information that can be stored about each item. Figure 1.1 provides a visualization of a table called teams with three columns named id, name, and conference. The table pictured also contains some data; each row in the table represents a single team and can store three pieces of information about that individual team: its id number, its name, and its conference (its division or league).

Figure 1.1. Tables have rows, and rows have columns

Here’s an example of a DDL statement; this is the statement that creates the database table pictured in Figure 1.1:

CREATE TABLE teams( id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY, name VARCHAR(37) NOT NULL, conference VARCHAR(2) NULL)The CREATE TABLE statement creates the teams table—but not the data—with three columns named id, name, and conference. This is a table used in the Teams and Games sample application, one of several sample applications used in the book. All the applications are described in Appendix B.

Note: The Order of Columns

Note that while tables are represented graphically with the columns always in the same order, this is for our ease of reference only. The database itself doesn’t care about the order of the columns.

It would be optimistic to expect you to understand everything in the CREATE TABLE statement above at this stage. (I’m sure some of you, new to SQL, might be wondering “What’s an id?” or “What does PRIMARY KEY do?” and so on.) We simply want to see an example of the CREATE TABLE statement, and not be sidetracked by design issues for the Teams and Games application.

Note that the keywords of the CREATE TABLE statement are all in capital letters, while the identifiers are all in lower case letters. This choice is part of my coding style.

Tip: Upper Case or Lower Case?

Although it’s of no consequence to SQL whether a font appears in caps or lower case, identifiers may indeed be case-sensitive. However, I’d strongly advise you to create your database objects with lower case letters to avoid syntax problems with unknown names.

Notice also the formatting and white space. Imagine having to read this SQL statement all on one long line:

CREATE TABLE teams ( id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY, ↵ name VARCHAR(37), conference VARCHAR(2) NULL )Neatness helps us to spot parts of the statement we have omitted or mispelled, like the NOT NULL that was accidentally left off the name column in the one line version of the statement above. Did you spot the omission before you read this?

Looking at the sample CREATE TABLE statement, we see that each of the three columns is given a data type (e.g., INTEGER, VARCHAR), and is also designated NULL or NOT NULL. Again, please don’t worry if these terms are new to you. We will discuss how they work and what they’re for in Chapter 9. This introductory chapter is not supposed to teach you the SQL statements in detail, merely introduce them to you and briefly describe their general purpose.

Are there other database objects that we can create besides tables? Yes. There are schemas, databases, views, triggers, procedures and several more but we’re getting ahead of ourselves again. Many CREATE statements are for administrative use only and hence solely used by designated database administrators (DBAs). Learning to be a DBA is such a large subject, it requires a book of its own just to cover its scope! Needless to say, our coverage of Database Administration topics will be kept to a minimum.

The ALTER Statements

As its name suggests, ALTER changes an object in a database. Here’s an example ALTER statement:

ALTER TABLE teams DROP COLUMN conferenceThe keyword DROP identifies what’s being dropped, or removed, from the table. In this example, the teams table is being altered by removing the conference column. Once the column is dropped, it’s no longer part of the table.

Note that if we tried to run the same ALTER statement for a second time, a syntax error would occur because the database cannot remove a column that does not exist from a table. Syntax errors can arise from more than just the improper construction of the SQL statement using keywords, identifiers, and constants. Many syntax errors arise from attempting to alter what are perceived (wrongly) to be the current structure or current contents of the table.

The DROP Statement

The DROP statement—to round out our trio of basic DDL statements—drops, removes, deletes, obliterates, cancels, blows away, and/or destroys the object it is dropping. After the DROP statement has been run, the object is gone.

The syntax is as simple as it can be:

DROP TABLE teamsTo summarize, the Data Definition Language statements CREATE, ALTER, and DROP allow us to manage database objects like tables and columns. In fact, they can be very effective when used together, such as when you need to start over.

Starting Over

Database development is usually iterative. Or rather, when building and testing your table (or tables—there is seldom only one) you will often find yourself repeating one of the following patterns:

CREATE, then testFirst, you create a table. Then you test it, perhaps by running some

SELECTqueries, to confirm that it works. The table is so satisfactory that it can be used exactly as it is, indefinitely. If only life were like this more often …

CREATE, then test …ALTER, then test …ALTER, then test …You create and test a table, and it’s good enough to be used regularly, such as when your web site goes live. You alter it occasionally, to make small changes. Small changes are easier than larger changes, especially if much code in the application depends on a particular table structure.

CREATE, then test …DROP,CREATE, then test …After creating and testing a table the first time, you realize it’s wrong. Or perhaps the table has been in use for some time, but is no longer adequate. You need to drop it, change your DDL, create it again (except that it’s different now), and then test again.

Dropping and recreating, or starting over, becomes much easier using an SQL script. A script is a text file of SQL statements that can be run as a batch to create and populate database objects. Maintaining a script allows you to start over easily. Improvements in the design—new tables, different columns, and so on—are incorporated into the SQL statements, and when the script is run, these SQL statements create the objects using the new design. Appendix C contains SQL scripts used for the sample applications in this book. These scripts and more are available to download from the web site for this book, at: https://www.sitepoint.com/premium/books/simply-sql/.

Data Manipulation Language

In the last section, we covered the three main SQL statements used in Data Definition Language. These were CREATE, ALTER, and DROP, and they are used to manage database objects like tables and columns.

Data Manipulation Language has three similar statements: INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE. These statements are used to manage the data within our tables and columns.

Remember the earlier CREATE statement example:

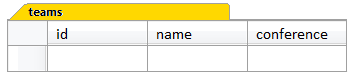

CREATE TABLE teams( id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY, name VARCHAR(37) NOT NULL, conference VARCHAR(2) NULL)This statement creates a table called teams that has three columns, pictured in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. The teams table

Once the table has been created, we say it exists. And once a table exists we may place our data in it, and we need a way to manage that data. We want to use the table the way it’s currently structured, so DDL is irrelevant for our purposes here (that is, changes aren’t required).

Instead, we need the three DML statements, INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE.

INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE

Until we put data into it, the table is empty. Managing our data may be accomplished in several ways: adding data to the table, updating some of the data, inserting some more data, or deleting some or all of it. Throughout this process, the table structure stays the same. Just the table contents change.

Let’s start by adding some data.

The INSERT Statement

The INSERT DML statement is similar to the CREATE DDL statement, in that it creates a new object in the database. The difference is that while CREATE creates a new table and defines its structure, INSERT creates a new row, inserting it and the data it contains into an existing table.

The INSERT statement inserts one or more rows. Here is our first opportunity to see rows in action. Here is how to insert a row of data into the teams table:

INSERT INTO teams ( id , name , conference )VALUES ( 9 , 'Riff Raff' , 'F' )The important part to remember, with our tabular structure in mind, is that the INSERT statement inserts entire rows. An INSERT statement should contain two comma-separated lists surrounded by parentheses. The first list identifies the columns in the new row into which the constants in the second list will be inserted. The first column named in the first list will receive the first constant in the second list, the second column has the second constant, and so on. There must be the same number of columns specified in the first list as constants given in the second, or an error will occur.

In the above example, three constants, 9, 'Riff Raff', and 'F' are specified in the VALUES clause. They are inserted, into the id, name, and conference columns respectively of a single new row of data in the teams table. Strings, such as 'Riff Raff', and 'F', are surrounded by single quotes to denote their beginning and end. We’ll look at strings in more detail in Chapter 9.

You are allowed (but it would be unusual) to write this INSERT statement as:

INSERT INTO teams ( conference , id , name )VALUES ( 'F' , 9 , 'Riff Raff' )We noted earlier that the database itself doesn’t care about the order of the columns within a table; however, it’s common practice to order the columns in an INSERT statement in the order in which they were created for our own ease of reference. As long as we make sure that we list columns and their intended values in the correct corresponding order, this version of the INSERT statement has exactly the same effect as the one preceding it.

Sometimes you may see an INSERT statement like this:

INSERT INTO teamsVALUES ( 9 , 'Riff Raff' , 'F' )This is perhaps more convenient, because it saves typing. The list of columns is assumed. The columns in the new row being inserted are populated according to their perceived position within the table, based on the order in which they were originally added when the table was created. However, we must supply a value for every column in this variation of INSERT; if we aren’t supplying a value for each and every column, which happens often, we can’t use it. If you do, the perceived list of columns will be longer than the list of values, and we’ll receive a syntax error.

My advice is to always specify the list of column names in an INSERT statement, as in the first example. It makes things much easier to follow.

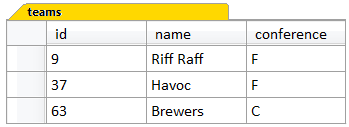

Finally, to insert more than one row, we could use the following variant of the INSERT statement:

INSERT INTO teams ( conference , id , name )VALUES ( 'F' , 9 , 'Riff Raff' ), ( 'F' , 37 , 'Havoc' ), ( 'C' , 63 , 'Brewers' )This example shows an INSERT statement that inserts three rows of data, and the result can be seen in Figure 1.3. Each row’s worth of data is specified within a set of parentheses, known as a row constructor, and each row constructor is separated by a comma.

Figure 1.3. The result of the INSERT statement: three rows of data

Next up, we want to change some of our data. For this, we use the UPDATE statement.

Important: A Note on Multiple Row Constructors

While the syntax in the above example, where one INSERT statement inserts multiple rows of data, is valid SQL, not every database system allows the INSERT statement to use multiple row constructors; those that do allow it include DB2, PostgreSQL, and MySQL. If your database system’s INSERT statement allows only one row to be inserted at a time, as is the case with SQL Server, simply run three INSERT statements, like so:

INSERT INTO teams ( id , conference , name ) VALUES ( 9 , 'F' , 'Riff Raff' ); INSERT INTO teams ( id , conference , name ) VALUES ( 37 , 'F' , 'Havoc' ); INSERT INTO teams ( id , conference , name ) VALUES ( 63 , 'C' , 'Brewers' );Notice that a semicolon (;) is used to separate SQL statements when we’re running multiple statements like this, not unlike its function in everyday language. Syntactically, the semicolon counts as a keyword in our scheme of keywords, identifiers, and constants. The comma, used to separate items in a list, does too.

The UPDATE Statement

The UPDATE DML statement is similar to the ALTER DDL statement, in that it produces a change. The difference is that, whereas ALTER changes the structure of a table, UPDATE changes the data contained within a table, while the table’s structure remains the same.

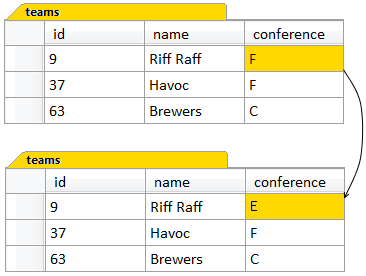

Let’s pretend that the team Riff Raff is changing conferences so we need to update the value in the conference column from F to E; we’ll write the following UPDATE statement:

UPDATE teamsSET conference = 'E'The above statement would change the value of the conference column in every row to E. This is not really what we wanted to do; we only wanted to change the value for one team. So we add a WHERE clause to limit the rows that will be updated:

UPDATE teamsSET conference = 'E' WHERE id = 9As shown in Figure 1.4, the above example will update only one value. The UPDATE clause alone would change the value of the conference column in every row, but the WHERE clause limits the change to just the one row: where the id column has the value 9. Whatever value the conference column had before, it now has E after the update.

Figure 1.4. Updating a row in a table

Sometimes, we’ll want to update values in multiple rows. The UPDATE statement will set column values for every row specified by the WHERE clause. The classic example, included in every textbook (so I simply had to include it too, although it isn’t part of any of our sample applications), is:

UPDATE personnelSET salary = salary * 1.07WHERE jobgrade <= 4Here, everyone is scoring a 7% raise, but only if their jobgrade is 4 or less. The UPDATE statement operates on multiple rows simultaneously, but only on those rows specified by the WHERE clause.

Notice that the existing value of the salary column is used to determine the new value of the salary column. UPDATE operates on each row independently of all others, which is exactly what we want, as it’s likely that the salary values are different for most rows.

Finally, there is the DELETE statement.

The DELETE Statement

The DELETE DML statement is similar to the DROP DDL statement, in that it removes objects from the database. The difference is that DROP removes a table from the database, while DELETE removes entire rows of data from a table, but the table continues to exist:

DELETEFROM teamsWHERE id = 63Once again, like the UPDATE statement, the scope of the DELETE statement is every row which satisfies the WHERE clause. If there is no WHERE clause, all the rows are deleted and the table is left empty; it has a structure, but no rows.

Finally, we are ready to meet the SELECT statement.

The SELECT Statement

The SELECT statement is usually called a query. Informally, all SQL statements are sometimes called queries (as in “I ran the DELETE query and received an error”), but the SELECT statement is truly a query because all it does is retrieve information from the database.

When we run a SELECT query against the database, it can retrieve data from one or more tables. Exactly how the data in multiple tables is combined, collated, compared, summarized, sorted, and presented— by a single query —is what makes SQL so wonderful.

The power is outstanding. The simplicity is amazing. SQL allows us to produce complex, customized information with a minimum of fuss, in a declarative, non-procedural way, using a small number of keywords.

SELECT is our fourth DML statement, although the operation it performs on the data is simply to retrieve it. Nothing is changed in the database. This is one reason why I prefer to discuss SELECT separately from the other three DML statements. Another is that it breaks up the pleasant symmetry between the DDL and DML statements:

DDL:

CREATE,ALTER,DROPDML:

INSERT,UPDATE,DELETE… andSELECT

The SELECT Retrieves Data

A simple SELECT statement has two parts, or clauses. Both are mandatory:

SELECT expression(s) involving keywords, identifiers, and constantsFROM tabular structure(s)The purpose of the SELECT statement is to retrieve data from the database:

the

SELECTclause specifies what you want to retrieve, andthe

FROMclause specifies where to retrieve it from.

The SELECT clause consists of one or more expressions involving keywords, identifiers, and constants. For example, this SELECT clause contains one expression, consisting of a single identifier:

SELECT nameFROM teamsIn this case the expression in the SELECT clause is name, which is a column name. However, the SELECT clause can contain many expressions, simply by listing them one after another, using commas as separators. For example, we may want to return the contents of several columns from rows in the teams table:

SELECT id, name, conferenceFROM teamsIn addition, each expression can be more complex, consisting of formulas, calculations, and so on. Ultimately then, the SELECT clause can be fairly complex, but it gives us the ability to include everything we need to return from the database. We examine the SELECT clause in Chapter Similarly, the FROM clause can be multifaceted. The FROM clause specifies the tabular structure(s) that contain the data that we want to retrieve. In this chapter we’ve seen sample queries in which the FROM clause specified a single table; complexity in the FROM clause occurs when more than one table is specified. I suggested earlier that tabular structures are one of the secrets to mastering SQL. We’ll cover them in detail in Chapter 3.

We’ll have an overview of the SELECT statement and its optional clauses, WHERE, GROUP BY, HAVING, and ORDER BY, in Chapter 2, and then look in detail at each of its clauses in chapters of their own.

The SELECT Statement Produces a Tabular Result Set

One important fact to remember about SELECT is that the result of running a SELECT query is a table.

When your web application (whether it is written in PHP, Java, or any other application language) runs a SELECT query, the database system returns a tabular structure, and the application handles it accordingly, as rows and columns of data. The query might return a list of selected items in a shopping cart, or posts in active forums threads, or whatever your web application needs to retrieve from your database.

We say that the SELECT statement produces a tabular result set. A result set is not actually a table in the database; it is derived from one or more tables in the database, and delivered, as tabular data, to your application.

One final introduction will complete our introduction to SQL: a comment about standard SQL.

Standard SQL

The nice thing about standards is that there are so many to choose from.

--Andrew S. Tanenbaum

In the beginning, I mentioned that SQL is a standard language. SQL has been standardized both nationally and internationally. If you are relatively new to SQL, do not look for any information on the standard just yet; you’re only going to confuse yourself. The SQL standard is exceedingly complex. The standard is also not freely available; it must be purchased from the relevant standards organisations.

The fact that the standard exists, though, is very important, and not just because it makes the skill of knowing SQL highly portable. The SQL standard is being adopted, in increasing measures, by all relational database systems. New database software releases always seem to mention some specific features of the standard that are now supported.

So as well as your knowledge of using simple SQL to produce comprehensive results being portable, there is a better chance that your next project’s database system will actually support the techniques that you already know. The industry and its practitioners are involved in a positive feedback loop.

And yet, there are differences between standard SQL and the SQL supported by various database systems you’ll encounter—sometimes maddeningly so. These variations in the language are called dialects of SQL. Numerous proprietary extensions to standard SQL have been invented for the various different database systems. These extensions can be considerable, occasionally pointless, often counterintuitive, and sometimes obscure.

There is only one sane way to cope.

Read The Fine Manual

Never memorize what you can look up in books.

--Albert Einstein

There will be occasions throughout this book where I’ll suggest referring to the manual. This will be the manual for your particular database system, whatever it may be. All database systems have manuals—often a great many—but fortunately, most are of interest only to DBAs. The one you want is typically called SQL Reference.

After more than 20 years of writing SQL, I still need to look up certain parts of SQL. Granted, I have committed most of standard SQL to memory, but there are always nuances that trip me up, and new features to learn, and all those proprietary extensions …

Tip: Finding the Manual

Appendix A gives links for downloading and installing five popular database systems: MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, DB2, and Oracle. In addition, links are given to the online SQL reference manuals for each of these systems.

Make it easy on yourself. Bookmark the SQL reference manual on your computer, on your company server, or on the Web. Be prepared for syntax errors. But be reassured that they’re easy to fix, if you know where to look in the manual.

Wrapping Up: an Introduction to SQL

In this chapter, we covered lots of ground. I hope you’re not feeling completely overwhelmed. The purpose of the whirlwind tour was simply to put the SQL language into the perspective that a typical web developer needs; there are SQL statements for everything you need to do, and, all things considered, these statements are quite simple.

The two basic types of SQL statement are:

Data Definition Language (DDL) statements:

CREATE,ALTER,DROPData Manipulation Language (DML) statements:

INSERT,UPDATE,DELETE… andSELECT

If you’re building your own database, you’ll need to know DDL, but you should have some experience using DML first. Designing databases is the subject of the last three chapters in this book.

As mentioned earlier, SQL is mainly about queries, and the SELECT statement is where it’s at. Chapter 2 begins our in-depth look at the SELECT statement, providing an overview of its six clauses.