What Is JavaScript?

WHAT'S IN THIS CHAPTER?

- Review of JavaScript history

- What JavaScript is

- How JavaScript and ECMAScript are related

- The different versions of JavaScript

WROX.COM DOWNLOADS FOR THIS CHAPTER

Please note that all the code examples for this chapter are available as a part of this chapter's code download on the book's website at www.wrox.com/go/projavascript4e on the Download Code tab.

When JavaScript first appeared in 1995, its main purpose was to handle some of the input validation that had previously been left to server-side languages such as Perl. Prior to that time, a round-trip to the server was needed to determine if a required field had been left blank or an entered value was invalid. Netscape Navigator sought to change that with the introduction of JavaScript. The capability to handle some basic validation on the client was an exciting new feature at a time when use of telephone modems was widespread. The associated slow speeds turned every trip to the server into an exercise in patience.

Since that time, JavaScript has grown into an important feature of every major web browser on the market. No longer bound to simple data validation, JavaScript now interacts with nearly all aspects of the browser window and its contents. JavaScript is recognized as a full programming language, capable of complex calculations and interactions, including closures, anonymous (lambda) functions, and even metaprogramming. JavaScript has become such an important part of the web that even alternative browsers, including those on mobile phones and those designed for users with disabilities, support it. Even Microsoft, with its own client-side scripting language called VBScript, ended up including its own JavaScript implementation in Internet Explorer from its earliest version.

The rise of JavaScript from a simple input validator to a powerful programming language could not have been predicted. JavaScript is at once a very simple and very complicated language that takes minutes to learn but years to master. To begin down the path to using JavaScript's full potential, it is important to understand its nature, history, and limitations.

A SHORT HISTORY

As the web gained popularity, a gradual demand for client-side scripting languages developed. At the time, most Internet users were connecting over a 28.8 kbps modem even though web pages were growing in size and complexity. Adding to users' pain was the large number of round-trips to the server required for simple form validation. Imagine filling out a form, clicking the Submit button, waiting 30 seconds for processing, and then being met with a message indicating that you forgot to complete a required field. Netscape, at that time on the cutting edge of technological innovation, began seriously considering the development of a client-side scripting language to handle simple processing.

In 1995, a Netscape developer named Brendan Eich began developing a scripting language called Mocha (later renamed as LiveScript) for the release of Netscape Navigator 2. The intention was to use it both in the browser and on the server, where it was to be called LiveWire.

Netscape entered into a development alliance with Sun Microsystems to complete the implementation of LiveScript in time for release. Just before Netscape Navigator 2 was officially released, Netscape changed LiveScript's name to JavaScript to capitalize on the buzz that Java was receiving from the press.

Because JavaScript 1.0 was such a hit, Netscape released version 1.1 in Netscape Navigator 3. The popularity of the fledgling web was reaching new heights, and Netscape had positioned itself to be the leading company in the market. At this time, Microsoft decided to put more resources into a competing browser named Internet Explorer. Shortly after Netscape Navigator 3 was released, Microsoft introduced Internet Explorer 3 with a JavaScript implementation called JScript (so called to avoid any possible licensing issues with Netscape). This major step for Microsoft into the realm of web browsers in August 1996 is now a date that lives in infamy for Netscape, but it also represented a major step forward in the development of JavaScript as a language.

Microsoft's implementation of JavaScript meant that there were two different JavaScript versions floating around: JavaScript in Netscape Navigator and JScript in Internet Explorer. Unlike C and many other programming languages, JavaScript had no standards governing its syntax or features, and the three different versions only highlighted this problem. With industry fears mounting, it was decided that the language must be standardized.

In 1997, JavaScript 1.1 was submitted to the European Computer Manufacturers Association (Ecma) as a proposal. Technical Committee #39 (TC39) was assigned to "standardize the syntax and semantics of a general purpose, cross-platform, vendor-neutral scripting language” (www.ecma-international.org/memento/TC39.htm). Made up of programmers from Netscape, Sun, Microsoft, Borland, NOMBAS, and other companies with interest in the future of scripting, TC39 met for months to hammer out ECMA-262, a standard defining a new scripting language named ECMAScript (often pronounced as “ek-ma-script”).

The following year, the International Organization for Standardization and International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) also adopted ECMAScript as a standard (ISO/IEC-16262). Since that time, browsers have tried, with varying degrees of success, to use ECMAScript as a basis for their JavaScript implementations.

JAVASCRIPT IMPLEMENTATIONS

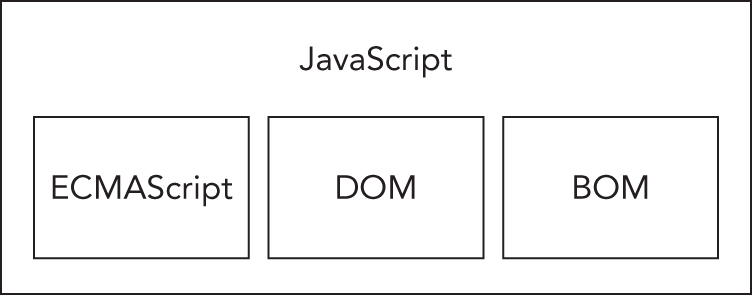

Though JavaScript and ECMAScript are often used synonymously, JavaScript is much more than just what is defined in ECMA-262. Indeed, a complete JavaScript implementation is made up of the following three distinct parts (see Figure 1-1):

FIGURE 1-1

- The Core (ECMAScript)

- The Document Object Model (DOM)

- The Browser Object Model (BOM)

ECMAScript

ECMAScript, the language defined in ECMA-262, isn't tied to web browsers. In fact, the language has no methods for input or output whatsoever. ECMA-262 defines this language as a base upon which more-robust scripting languages may be built. Web browsers are just one host environment in which an ECMAScript implementation may exist. A host environment provides the base implementation of ECMAScript and implementation extensions designed to interface with the environment itself. Extensions, such as the Document Object Model (DOM), use ECMAScript's core types and syntax to provide additional functionality that's more specific to the environment. Other host environments include NodeJS, a server-side JavaScript platform, and the increasingly obsolete Adobe Flash.

What exactly does ECMA-262 specify if it doesn't reference web browsers? On a very basic level, it describes the following parts of the language:

- Syntax

- Types

- Statements

- Keywords

- Reserved words

- Operators

- Global objects

ECMAScript is simply a description of a language implementing all of the facets described in the specification. JavaScript implements ECMAScript, but so does Adobe ActionScript.

ECMAScript Editions

The different versions of ECMAScript are defined as editions (referring to the edition of ECMA-262 in which that particular implementation is described). The most recent edition of ECMA-262 is edition 7, released in 2016. The first edition of ECMA-262 was essentially the same as Netscape's JavaScript 1.1 but with all references to browser-specific code removed and a few minor changes: ECMA-262 required support for the Unicode standard (to support multiple languages) and that objects be platform-independent (Netscape JavaScript 1.1 actually had different implementations of objects, such as the Date object, depending on the platform). This was a major reason why JavaScript 1.1 and 1.2 did not conform to the first edition of ECMA-262.

The second edition of ECMA-262 was largely editorial. The standard was updated to get into strict agreement with ISO/IEC-16262 and didn't feature any additions, changes, or omissions. ECMAScript implementations typically don't use the second edition as a measure of conformance.

The third edition of ECMA-262 was the first real update to the standard. It provided updates to string handling, the definition of errors, and numeric outputs. It also added support for regular expressions, new control statements, try-catch exception handling, and small changes to better prepare the standard for internationalization. To many, this marked the arrival of ECMAScript as a true programming language.

The fourth edition of ECMA-262 was a complete overhaul of the language. In response to the popularity of JavaScript on the web, developers began revising ECMAScript to meet the growing demands of web development around the world. In response, Ecma TC39 reconvened to decide the future of the language. The resulting specification defined an almost completely new language based on the third edition. The fourth edition includes strongly typed variables, new statements and data structures, true classes and classical inheritance, and new ways to interact with data.

As an alternate proposal, a specification called “ECMAScript 3.1,” was developed as a smaller evolution of the language by a subcommittee of TC39, who believed that the fourth edition was too big of a jump for the language. The result was a smaller proposal with incremental changes to ECMAScript that could be implemented on top of existing JavaScript engines. Ultimately, the ES3.1 subcommittee won over support from TC39, and the fourth edition of ECMA-262 was abandoned before officially being published.

ECMAScript 3.1 became ECMA-262, fifth edition, and was officially published on December 3, 2009. The fifth edition sought to clarify perceived ambiguities of the third edition and introduce additional functionality. The new functionality includes a native JSON object for parsing and serializing JSON data, methods for inheritance and advanced property definition, and the inclusion of a new strict mode that slightly augments how ECMAScript engines interpret and execute code. The fifth edition saw a maintenance revision in June 2011; this was merely for corrections in the specification and introduced no new language or library features.

The sixth edition of ECMA-262—colloquially referred to as ES6, ES2015, or ES Harmony—was published in June 2015, and contains arguably the most important collection of enhancements to the specification since its inception. ES6 adds formal support for classes, modules, iterators, generators, arrow functions, promises, reflection, proxies, and a host of new data types.

The seventh edition of ECMA-262, dubbed ES7 or ES2016, was published in June of 2016. This revision included only a handful of syntactical additions such as Array.prototype.includes and the exponentiation operator.

The eighth edition of ECMA-262, called ES8 or ES2017, was finalized in January of 2017. This revision included asynchronous iteration, rest and spread properties, a collection of new regular expression features, a Promise finally() catchall handler, and template literal revisions.

The ninth edition of ECMA-262 is still being finalized, but it already has a large number of features in stage 3. Its most significant addition will likely be dynamic importing of ES6 modules.

What Does ECMAScript Conformance Mean?

ECMA-262 lays out the definition of ECMAScript conformance. To be considered an implementation of ECMAScript, an implementation must do the following:

- Support all "types, values, objects, properties, functions, and program syntax and semantics” as they are described in ECMA-262.

- Support the Unicode character standard.

Additionally, a conforming implementation may do the following:

- Add “additional types, values, objects, properties, and functions” that are not specified in ECMA-262. ECMA-262 describes these additions as primarily new objects or new properties of objects not given in the specification.

- Support “program and regular expression syntax” that is not defined in ECMA-262 (meaning that the built-in regular-expression support is allowed to be altered and extended).

These criteria give implementation developers a great amount of power and flexibility for developing new languages based on ECMAScript, which partly accounts for its popularity.

ECMAScript Support in Web Browsers

Netscape Navigator 3 shipped with JavaScript 1.1 in 1996. That same JavaScript 1.1 specification was then submitted to Ecma as a proposal for the new standard, ECMA-262. With JavaScript's explosive popularity, Netscape was very happy to start developing version 1.2. There was, however, one problem: Ecma hadn't yet accepted Netscape's proposal.

Shortly after Netscape Navigator 3 was released, Microsoft introduced Internet Explorer 3. This version of IE shipped with JScript 1.0, which was supposed to be equivalent to JavaScript 1.1. However, because of undocumented and improperly replicated features, JScript 1.0 fell far short of JavaScript 1.1.

Netscape Navigator 4 was shipped in 1997 with JavaScript 1.2 before the first edition of ECMA-262 was accepted and standardized later that year. As a result, JavaScript 1.2 is not compliant with the first edition of ECMAScript even though ECMAScript was supposed to be based on JavaScript 1.1.

The next update to JScript occurred in Internet Explorer 4 with JScript version 3.0 (version 2.0 was released in Microsoft Internet Information Server version 3.0 but was never included in a browser). Microsoft put out a press release touting JScript 3.0 as the first truly Ecma-compliant scripting language in the world. At that time, ECMA-262 hadn't yet been finalized, so JScript 3.0 suffered the same fate as JavaScript 1.2: it did not comply with the final ECMAScript standard.

Netscape opted to update its JavaScript implementation in Netscape Navigator 4.06 to JavaScript 1.3, which brought Netscape into full compliance with the first edition of ECMA-262. Netscape added support for the Unicode standard and made all objects platform-independent while keeping the features that were introduced in JavaScript 1.2.

When Netscape released its source code to the public as the Mozilla project, it was anticipated that JavaScript 1.4 would be shipped with Netscape Navigator 5. However, a radical decision to completely redesign the Netscape code from the bottom up derailed that effort. JavaScript 1.4 was released only as a server-side language for Netscape Enterprise Server and never made it into a web browser.

By 2008, the five major web browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Chrome, and Opera) all complied with the third edition of ECMA-262. Internet Explorer 8 was the first to start implementing the fifth edition of ECMA-262 specification and delivered complete support in Internet Explorer 9. Firefox 4 soon followed suit. The following table lists ECMAScript support in the most popular web browsers.

| BROWSER | ECMASCRIPT COMPLIANCE |

| Netscape Navigator 2 | — |

| Netscape Navigator 3 | — |

| Netscape Navigator 4–4.05 | — |

| Netscape Navigator 4.06–4.79 | Edition 1 |

| Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) | Edition 3 |

| Internet Explorer 3 | — |

| Internet Explorer 4 | — |

| Internet Explorer 5 | Edition 1 |

| Internet Explorer 5.5–8 | Edition 3 |

| Internet Explorer 9 | Edition 5* |

| Internet Explorer 10–11 | Edition 5 |

| Edge 12+ | Edition 6 |

| Opera 6–7.1 | Edition 2 |

| Opera 7.2+ | Edition 3 |

| Opera 15–28 | Edition 5 |

| Opera 29–35 | Edition 6* |

| Opera 36+ | Edition 6 |

| Safari 1–2.0. x | Edition 3* |

| Safari 3.1–5.1 | Edition 5* |

| Safari 6–8 | Edition 5 |

| Safari 9+ | Edition 6 |

| iOS Safari 3.2–5.1 | Edition 5* |

| iOS Safari 6–8.4 | Edition 5 |

| iOS Safari 9.2+ | Edition 6 |

| Chrome 1–3 | Edition 3 |

| Chrome 4–22 | Edition 5* |

| Chrome 23+ | Edition 5 |

| Chrome 42–48 | Edition 6* |

| Chrome 49+ | Edition 6 |

| Firefox 1–2 | Edition 3 |

| Firefox 3.0. x –20 | Edition 5* |

| Firefox 21–44 | Edition 5 |

| Firefox 45+ | Edition 6 |

*Incomplete implementations

The Document Object Model

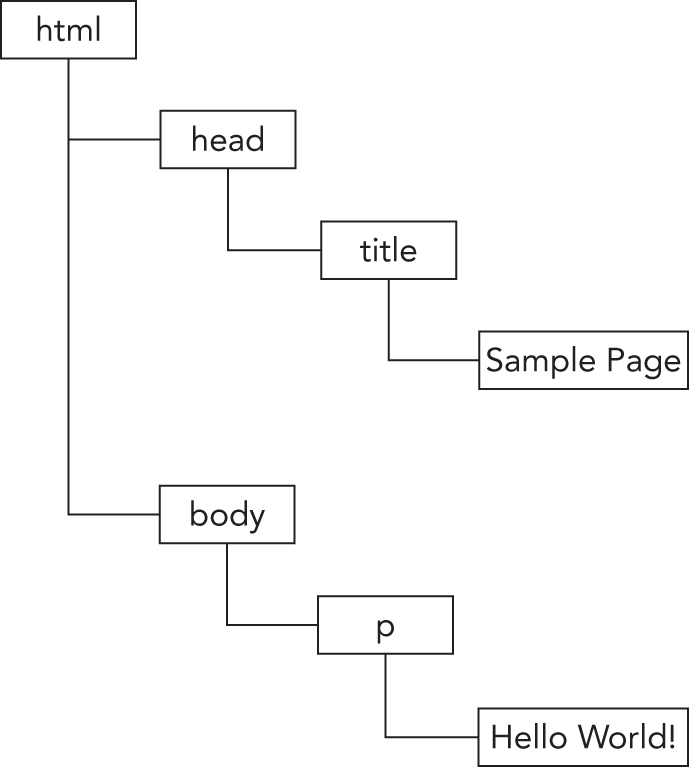

The Document Object Model (DOM) is an application programming interface (API) for XML that was extended for use in HTML. The DOM maps out an entire page as a hierarchy of nodes. Each part of an HTML or XML page is a type of node containing different kinds of data. Consider the following HTML page:

<html> <head> <title>Sample Page</title> </head> <body> <p> Hello World!</p> </body></html>This code can be diagrammed into a hierarchy of nodes using the DOM (see Figure 1-2).

FIGURE 1-2

By creating a tree to represent a document, the DOM allows developers an unprecedented level of control over its content and structure. Nodes can be removed, added, replaced, and modified easily by using the DOM API.

Why the DOM Is Necessary

With Internet Explorer 4 and Netscape Navigator 4 each supporting different forms of Dynamic HTML (DHTML), developers for the first time could alter the appearance and content of a web page without reloading it. This represented a tremendous step forward in web technology but also a huge problem. Netscape and Microsoft went separate ways in developing DHTML, thus ending the period when developers could write a single HTML page that could be accessed by any web browser.

It was decided that something had to be done to preserve the cross-platform nature of the web. The fear was that if someone didn't rein in Netscape and Microsoft, the web would develop into two distinct factions that were exclusive to targeted browsers. It was then that the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the body charged with creating standards for web communication, began working on the DOM.

DOM Levels

DOM Level 1 became a W3C recommendation in October 1998. It consisted of two modules: the DOM Core, which provided a way to map the structure of an XML-based document to allow for easy access to and manipulation of any part of a document, and the DOM HTML, which extended the DOM Core by adding HTML-specific objects and methods.

Note

Note that the DOM is not JavaScript-specific and indeed has been implemented in numerous other languages. For web browsers, however, the DOM has been implemented using ECMAScript and now makes up a large part of the JavaScript language.

Whereas the goal of DOM Level 1 was to map out the structure of a document, the aims of DOM Level 2 were much broader. This extension of the original DOM added support for mouse and user-interface events (long supported by DHTML), ranges, and traversals (methods to iterate over a DOM document), and support for Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) through object interfaces. The original DOM Core introduced in Level 1 was also extended to include support for XML namespaces.

DOM Level 2 introduced the following new modules of the DOM to deal with new types of interfaces:

- DOM views —Describes interfaces to keep track of the various views of a document (the document before and after CSS styling, for example)

- DOM events —Describes interfaces for events and event handling

- DOM style —Describes interfaces to deal with CSS-based styling of elements

- DOM traversal and range —Describes interfaces to traverse and manipulate a document tree

DOM Level 3 further extends the DOM with the introduction of methods to load and save documents in a uniform way (contained in a new module called DOM Load and Save) and methods to validate a document (DOM Validation). In Level 3, the DOM Core is extended to support all of XML 1.0, including XML Infoset, XPath, and XML Base.

Presently, the W3C no longer maintains the DOM as a set of levels, but rather as the DOM Living Standard, snapshots of which are termed DOM4. Among its introductions is the addition of Mutation Observers to replace Mutation Events.

Note

When reading about the DOM, you may come across references to DOM Level 0. Note that there is no standard called DOM Level 0; it is simply a reference point in the history of the DOM. DOM Level 0 is considered to be the original DHTML supported in Internet Explorer 4.0 and Netscape Navigator 4.0.

Other DOMs

Aside from the DOM Core and DOM HTML interfaces, several other languages have had their own DOM standards published. The languages in the following list are XML-based, and each DOM adds methods and interfaces unique to a particular language:

- Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.0

- Mathematical Markup Language (MathML) 1.0

- Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language (SMIL)

Additionally, other languages have developed their own DOM implementations, such as Mozilla's XML User Interface Language (XUL). However, only the languages in the preceding list are standard recommendations from W3C.

DOM Support in Web Browsers

The DOM had been a standard for some time before web browsers started implementing it. Internet Explorer made its first attempt with version 5, but it didn't have any realistic DOM support until version 5.5, when it implemented most of DOM Level 1. Internet Explorer didn't introduce new DOM functionality in versions 6 and 7, though version 8 introduced some bug fixes.

For Netscape, no DOM support existed until Netscape 6 (Mozilla 0.6.0) was introduced. After Netscape 7, Mozilla switched its development efforts to the Firefox browser. Firefox 3+ supports all of Level 1, nearly all of Level 2, and some parts of Level 3. (The goal of the Mozilla development team was to build a 100 percent standards-compliant browser, and their work paid off.)

DOM support became a huge priority for most browser vendors, and efforts have been ongoing to improve support with each release. The following table shows DOM support for popular browsers.

| BROWSER | DOM COMPLIANCE |

| Netscape Navigator 1.–4.x | — |

| Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) | Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial) |

| Internet Explorer 2–4.x | — |

| Internet Explorer 5 | Level 1 (minimal) |

| Internet Explorer 5.5–8 | Level 1 (almost all) |

| Internet Explorer 9+ | Level 1, Level 2, Level 3 |

| Edge | Level 1, Level 2, Level 3 |

| Opera 1–6 | — |

| Opera 7–8.x | Level 1 (almost all), Level 2 (partial) |

| Opera 9–9.9 | Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial) |

| Opera 10+ | Level 1, Level 2, Level 3 (partial) |

| Safari 1.0.x | Level 1 |

| Safari 2+ | Level 1, Level 2 (partial), Level 3 (partial) |

| iOS Safari 3.2+ | Level 1, Level 2 (partial), Level 3 (partial) |

| Chrome 1+ | Level 1, Level 2 (partial), Level 3 (partial) |

| Firefox 1+ | Level 1, Level 2 (almost all), Level 3 (partial) |

Note

The content of this compatibility table is changing all the time and should only be used as a historical reference.

The Browser Object Model

The Internet Explorer 3 and Netscape Navigator 3 browsers featured a Browser Object Model (BOM) that allowed access and manipulation of the browser window. Using the BOM, developers can interact with the browser outside of the context of its displayed page. What made the BOM truly unique, and often problematic, was that it was the only part of a JavaScript implementation that had no related standard. This changed with the introduction of HTML5, which sought to codify much of the BOM as part of a formal specification. Thanks to HTML5, a lot of the confusion surrounding the BOM has dissipated.

Primarily, the BOM deals with the browser window and frames, but generally any browser-specific extension to JavaScript is considered to be a part of the BOM. The following are some such extensions:

- The capability to pop up new browser windows

- The capability to move, resize, and close browser windows

- The

navigatorobject, which provides detailed information about the browser - The

locationobject, which gives detailed information about the page loaded in the browser - The

screenobject, which gives detailed information about the user's screen resolution - The

performanceobject, which gives detailed information about the browser's memory consumption, navigational behavior, and timing statistics - Support for cookies

- Custom objects such as

XMLHttpRequestand Internet Explorer'sActiveXObject

Because no standards existed for the BOM for a long time, each browser has its own implementation. There are some de facto standards, such as having a window object and a navigator object, but each browser defines its own properties and methods for these and other objects. With HTML5 now available, the implementation details of the BOM are expected to grow in a much more compatible way. A detailed discussion of the BOM is included in the chapter “Browser Object Model.”

JAVASCRIPT VERSIONS

Mozilla, as a descendant from the original Netscape, is the only browser vendor that has continued the original JavaScript version-numbering sequence. When the Netscape source code was spun off into an open-source project (named the Mozilla Project), the last browser version of JavaScript was 1.3. (As mentioned previously, version 1.4 was implemented on the server exclusively.) As the Mozilla Foundation continued work on JavaScript, adding new features, keywords, and syntaxes, the JavaScript version number was incremented. The following table shows the JavaScript version progression in Netscape/Mozilla browsers.

| BROWSER | JAVASCRIPT VERSION |

| Netscape Navigator 2 | 1.0 |

| Netscape Navigator 3 | 1.1 |

| Netscape Navigator 4 | 1.2 |

| Netscape Navigator 4.06 | 1.3 |

| Netscape 6+ (Mozilla 0.6.0+) | 1.5 |

| Firefox 1 | 1.5 |

| Firefox 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Firefox 2 | 1.7 |

| Firefox 3 | 1.8 |

| Firefox 3.5 | 1.8.1 |

| Firefox 3.6 | 1.8.2 |

| Firefox 4 | 1.8.5 |

The numbering scheme was based on the idea that Firefox 4 would feature JavaScript 2.0, and each increment in the version number prior to that point indicates how close the JavaScript implementation is to the 2.0 proposal. Though this was the original plan, the evolution of JavaScript happened in such a way that this was no longer possible. There is currently no target implementation for JavaScript 2.0, and this style of versioning ceased past the Firefox 4 release.

Note

It's important to note that only the Netscape/Mozilla browsers followed this versioning scheme. Internet Explorer, for example, has different version numbers for JScript. These JScript versions don't correspond whatsoever to the JavaScript versions mentioned in the preceding table. Furthermore, most browsers talk about JavaScript support in relation to their level of ECMAScript compliance and DOM support.

SUMMARY

JavaScript is a scripting language designed to interact with web pages and is made up of the following three distinct parts:

- ECMAScript, which is defined in ECMA-262 and provides the core functionality

- The Document Object Model (DOM), which provides methods and interfaces for working with the content of a web page

- The Browser Object Model (BOM), which provides methods and interfaces for interacting with the browser

There are varying levels of support for the three parts of JavaScript across the five major web browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, and Opera). Support for ECMAScript 5 is generally good across all browsers, and support for ECMAScript 6 and 7 is growing. Support for the DOM varies, but Level 3 compliance is increasingly normative. The BOM, codified in HTML5, can vary from browser to browser, though there are some commonalities that are assumed to be available.