Get Started

Before you start your project you’ll need to assemble a crack multidisciplinary team and clearly define the opportunity area you want to innovate. You’ll tighten up its focus and scope, getting alignment with your team, sponsor and key stakeholders. Finally, you’ll have fun designing a space to play home for your team. In this stage you will learn how to set up for success.

So you’ve decided to go on an innovation journey. How do you set yourself and your team up for success on a journey that will be unpredictable, complex and ambiguous at times, and iterative, not linear, in nature? Before you dive into the real work of identifying customer needs you need to make sure you and your team are ready to get started.

In this chapter I’ll show you how to set yourself up for success. (Keep in mind this chapter isn’t meant to be a replacement for good project management —you’ll need that too — or the development of a proper innovation strategy.)

Preparing your team

Innovation is a team sport. I liken it to team orienteering rather than a relay race. Not only is the orienteering trail more unpredictable than an athletics track, it also requires the team to work together side by side to navigate their way around the course, unlike handing over a baton to the next runner in a relay. Too often in organisations we work in our siloed departments, doing handovers from one team to the next. At each handover we risk losing the integrity of the original insights and ideas, as each team intentionally or unintentionally adds their own spin or flavour to the solution.

Team makeup

Just like a sports team you’re going to need an experienced cross-functional team with a variety and depth of skills to complete the wide range of tasks required to develop a new innovation. Having a ‘true cross-functional team’ is fifth in Cooper’s top nine success factors of innovation, as discussed in the section, My journey of discovery to innovation flow.

You also want diversity to ensure expansive thinking, insights and ideas, as well as connection to different networks, both internally and externally. Having a multidisciplinary team will help with this, but you also want diversity of backgrounds, cultures, gender, age and mindset.

Ideally you’ll have a core team of around six to ten people. The bigger your team gets the harder it’s going to be to schedule meetings, especially if the project is in addition to your day job. According to Head of Innovation at Method, an eco-friendly cleaning product company, Joshua Handy, one of the biggest killers of innovation is ‘having to schedule a meeting and create a PowerPoint presentation’. The components of this team will vary by industry, but will likely include a:

- project ‘innovation’ leader

- project manager (highly recommended)

- research specialist

- marketing specialist

- sales specialist

- development/technology specialist

- packaging specialist

- supply chain specialist

- finance specialist

- design specialist.

Often the project leader is also one of the functional specialists. Having a dedicated project manager means everyone can focus on their specialist roles and leave the project management to the project manager. These people will be engaged throughout the project journey, not just for their specific functional expertise.

You’ll also need a project sponsor. Whether the innovation project is full time or in addition to your day job, you are going to need senior sponsorship to provide project legitimacy, ground cover, free up the necessary time and resources, make connections and remove barriers.

In addition to the core team you’ll have a ‘bench’ of subject matter experts and suppliers that you’ll need to draw on from time to time, for example legal, customer recruitment agencies, visualisers and facilitators. The facilitator will guide you through the key workshops and possibly even facilitate the entire journey. It is important the facilitator stays neutral about decisions, so as to encourage everyone’s input. For this reason the project leader should not be the facilitator. This book is written as if directed to the innovation leader or facilitator, but is equally useful to anyone interested in designing and running a better innovation journey to create innovations your customers will love.

Team performance

Just like a sports team, you won’t win at innovation if you haven’t got a cohesive and high-performing team. Even if on paper it is the best list of experts anyone could muster, if they don’t play well together, you won’t succeed. We’ve all been on good and bad teams. Table 1.1 shows some of their characteristics.

Table 1.1worst and best team characteristics

| Worst | Best |

| Political | Imaginative |

| Personal agendas are pursued | Trusting |

| Directionless | Respectful |

| Error prone | Innovative |

| High conflict | Fun |

| No personal growth | Roles are clear |

| Self-centred | Supportive |

| Prone to blame | Good leadership |

| Flexible |

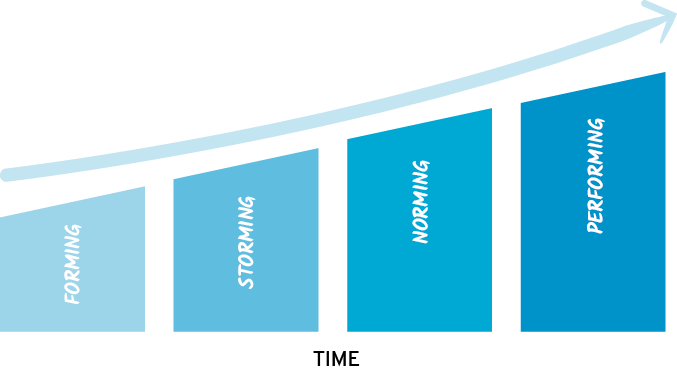

We can look at team development and performance through the ‘forming to performing’ model developed by Bruce Tuckman in 1965, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: team development — stages

Source: Adapted from concepts by Bruce Tuckman

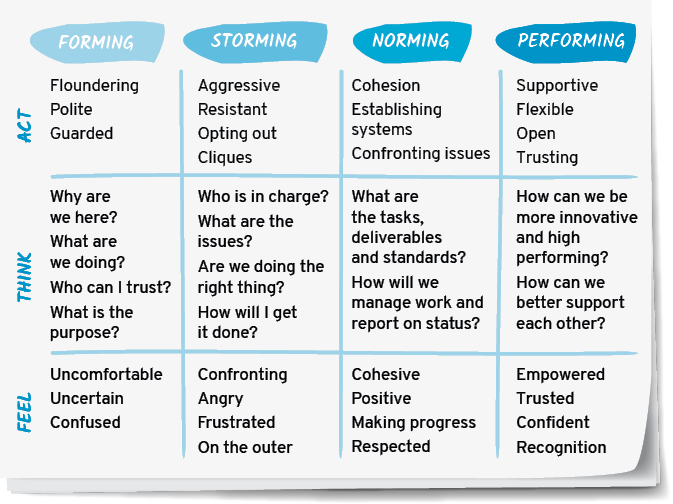

All newly formed teams go through forming, storming, norming and performing stages. All stages, according to Tuckman, are ‘necessary and inevitable’, so the key is to go through the first two stages before the project properly starts. This is a key objective of the ‘Get Started’ stage. Figure 1.2 (overleaf) goes into what each stage looks and feels like in more detail by looking at it from three different lenses:

- act

- think

- feel.

Figure 1.2: team development — how they act, think and feel by stage

Source: Adapted from concepts by Bruce Tuckman

By understanding these stages, the essentials for good teamwork and what a successful team looks like, we can look to accelerate team development. Some key essentials for a high-functioning team, identified from both Tuckman’s work and my own experience, are:

- a clear goal

- a sense of drive/passion

- agreement on priorities

- deadlines/deliverables

- ownership of decisions and/or a bias towards action

- communication

- trust

- helpfulness between team members

- commitment/dedication

- information sharing

- a team to play against.

A successful team:

- likes working together

- communicates the bad news

- argues/challenges each other

- trusts each other

- knows what each other are doing

- actively shares information

- communicates all the time

- respects the contribution of others

- wants to win.

We can accelerate team development through:

- pre-project preparation

- a project kick-off workshop

- team building events

- clarifying individual roles

- managing conflict constructively.

Once you’ve selected your team you can accelerate team development at your project kick-off workshop and by running a fun team-building event either at the beginning or end of the workshop.

Tips

Taking new methodologies into new teams, locations or organisations can be met with some resistance. Human beings don’t always initially respond well to change. Business Design and Integrative Thinking expert Roger Martin has some good tips for applying customer-centric innovation in new or hostile territories:

- Reframe extreme views as a creative challenge and apply the method to solve for them.

- Empathise with your colleagues on extremes (those who are invested in traditional analytical business thinking and new Design Thinking).

- Learn to speak the languages of both extremes.

- Step back from perfection (and don’t be a zealot).

- Turn the future into the past by validating through experiments.

Defining the challenge and planning the project

Now it’s time to discuss what you’ll be diving into — your innovation challenge!

Before starting a project with a client or internal team I ask them to complete a project brief on a provided template. Not only does this give me a better chance of successfully meeting their needs, it is also a good test of their commitment to the project. After all, if they can’t make the time to complete the brief then it probably isn’t worth pursuing. Sometimes I help them by interviewing them about the project, using the template as a discussion guide. I write it up and send it back to them for review and sign-off. Other times I run a project kick-off meeting with the newly formed team to complete each of the elements; this can only happen if I’ve already had at least an initial briefing from the project sponsor. In this case, after the workshop I would take the sponsor through the write-up for review and sign-off. The elements I like to cover in the project brief, which you can tailor and add to, are:

- What success looks like. What’s our end goal, why are we doing this, what are the key objectives and deliverables?

- Challenge statement. What’s our single-minded, positive and exciting project definition?

- Target customer. Who are we solving for?

- Scope. What’s in scope and out of scope?

- Existing ideas and hypotheses. What existing ideas, development work or hypotheses should we explore?

- Existing research and background materials. What background materials are relevant to immerse the team in? What existing research has been done on the opportunity space you are exploring?

- Constraints. Is there anything we definitely can’t change?

- Barriers. Are there obstacles we need to be aware of and manage?

- Stakeholders. Who are our key stakeholders?

- Timing and budget. When does this need to go live by? What budget is set aside and signed off?

A critical element in the project brief is a clearly defined and engaging challenge. We can’t be all things to all people, and every organisation and project has limited time and resources. It may sound counterintuitive, but creativity and innovation actually love focus. Clearly articulating an opportunity first actually better allows people to unleash their creativity within that space. ‘Focus and simplicity’ were also one of Steve Jobs’s mantras, and who are we to argue with the great man? So we need to decide early where we are going to focus those resources and where we are not.

Tips

The challenge statement should come from your briefing by the sponsor — but let your team modify it if they have good cause. It also helps with team buy-in, and can lead to a better articulation.

Project kick-off workshop

In the project kick-off, a good starting agenda that you can modify to your challenge is the following:

- Welcome

- Introductions

- Energiser and/or team building exercise

- The agenda

- Project introduction

- Team organisation and roles

- Project brief elements (from the previous section)

- Project planning

- Risk analysis

- Future meetings and actions.

The innovation opportunity

Your team should be starting with a prioritised innovation opportunity that has been briefed to you by your sponsor. Or if you’re an intrapreneur or entrepreneur it may be an opportunity area you’ve uncovered or have a passion for. What I mean by ‘innovation opportunity’ is a large, well-defined space for growth, within the organisation’s overall growth and innovation strategy, that needs to be explored and developed further through the innovation process to be realised. An innovation opportunity:

- is a level or two higher than an idea

- is a space for innovation that should lead to several customer-centric sub-opportunities and ideas

- should inspire ideas, but not have an idea baked into it

- could be a trend, technology, market insight, customer group, customer occasion or a combination of these

- is framed with the end customer in mind.

Here are some example innovation opportunities:

- Financial services organisation. How might we better meet the financial needs of the growing small business market?

- Airline. How might we improve the long-haul travel experience?

- Fitness organisation. How might we better meet the fitness needs of the youth market?

- Food manufacturer. How might we better serve healthy, busy families?

- Smart phone company. How might we better meet the needs of people with active lifestyles?

- Cycling company. How might we get more women riding?

- Government organisation. How might we encourage more people to vote?

- HR team. How might we improve the onboarding experience?

As I’ve mentioned, this chapter isn’t a replacement for proper innovation strategy development or portfolio management. They’re topics worthy of a book themselves. Therefore, in this chapter I won’t be addressing how to uncover strategic high-level opportunities for growth like the examples above. What I’ll be focusing on in this section is how to frame up these already-identified opportunities to get your innovation journey off to a good start. If you don’t have an innovation strategy and opportunity area to focus on, then it’s worth taking a step back and deciding where you want to play first and why. This might involve engaging your strategy and research teams to do an environmental scan and then analyse and identify some sizeable opportunities that will unlock growth and fit with your organisation’s overall strategy.

Tip

I recommend working on one innovation opportunity at a time, with up to four teams working in parallel on it. Having four teams work on a challenge simultaneously gives you different ways into the opportunity space and ways of solving it. You can run this by giving each team a different focus, for example a different customer segment or occasion.

Make it defined and engaging

So you have your prioritised innovation opportunity. Now we need to ensure it’s clearly defined and engaging.

We start by clarifying the challenge and then we rephrase it to ensure it is customer-centric, inspiring and engaging.

Some tools we use to help us clarify the challenge in the kick-off workshop are:

- Focus: zoom in and zoom out

- Scope

and a tool we use for clearly articulating the challenge is:

- Rephrase the challenge.

1. Focus: zoom in and zoom out

| TIME 15–25 minutes |

| PEOPLE Core team of 6–10 |

| MATERIALS A whiteboard/flip chart paper, markers and sticky notes |

- Draw a funnel on flip chart paper or a whiteboard.

- Write your current challenge statement (probably from your sponsor) on a sticky note and place it in the middle of your funnel.

- Now generate new statements by zooming in — capturing each iteration on sticky notes and plotting on the flip chart paper or whiteboard.

In order to zoom in try asking:

- – How are we going to do this?

- – What are the parts of this?

- Now generate new statements by zooming out — capturing each iteration on sticky notes and plotting on the flip chart paper or whiteboard.

In order to zoom out try asking:

- – Why are we doing this?

- – What is this a part of?

- Once you have settled on the right level, highlight it on your flip chart paper or whiteboard.

The higher up the funnel the more dollars, time and resources you’ll need. The lower down the funnel the closer it gets to being a solution and not an opportunity.

For example, let’s imagine we are working for an airline and the innovation opportunity area is ‘improving the long-haul flying experience’, as shown in figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: zooming in and out on long-haul flights

We zoom in by asking how we might do this and what are the parts of this. This leads to us narrowing our focus and we might come up with ‘improving the long-haul in-flight experience’ or go even narrower, like ‘improving the seats’. The first one sounds acceptable, assuming we know from research that there is room to improve the in-flight experience. Improving seats is starting to sound like a solution. But we haven’t actually premeditated how to improve the seats. Whereas, if we said ‘improve the seats by increasing the width by 30 millimetres’ then this would be a solution and we are being too specific.

We then zoom out, asking ‘why are we doing this?’ and ‘what is this a part of?’. We might come up with ‘to gain competitor advantage’ and, even broader, ‘to increase customer loyalty’. Now these two are getting too broad and abstract. While they might be the beginnings of good project objectives, they’re not specific enough for a project.

Let’s say we then go back to our sponsor and say that we feel ‘improving the long-haul flying experience’ would be a huge undertaking as one project, and recommend breaking it down into multiple projects with a steering group overseeing all the projects. We suggest the project could be broken down into:

- planning and booking the trip

- travel to the airport and checking in and pre-departure

- boarding the flight and flying

- arrival and getting to your first destination.

Hopefully from this example you can see that there is a sliding scale that you are playing with, from being too broad and abstract at the top to too specific, narrow and almost a solution at the bottom. You want your challenge to be in the sweet spot, or what I like to call the ‘Goldilocks zone’. Also, depending on resourcing you may need to move lower down the funnel.

2. Scope

| TIME 15–25 minutes |

| PEOPLE Core team of 6–10 |

| MATERIALS A whiteboard/flip chart paper, markers and sticky notes |

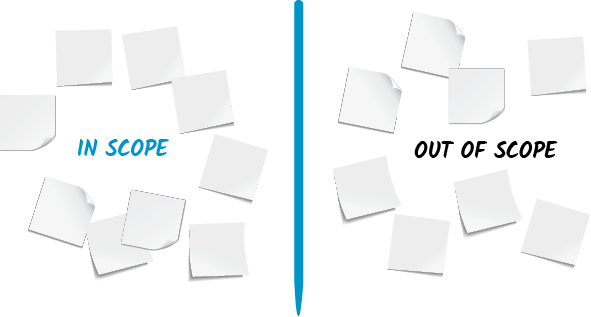

Now that you have the right level of focus it is important to clarify further where to focus — what’s in scope and out of scope for the project? ‘Scoping’ helps you clarify this.

- Draw or create a vertical line on the wall, table or floor. Label the left side of the line as ‘in scope’ and right side as ‘out of scope’.

- Write as many questions about the focus of the project as you and your team can in five minutes. You can be quite prescriptive to ensure you cover all avenues by using a framework such as 5W: Who for? When/Where? Why? What? For example, ‘Are families in scope?’ ‘Is breakfast in scope?’ And reviewing the whole supply chain and/or business model, for example ‘Is retail in or out of scope?’ ‘Is frozen food in scope?’ Write one question per piece of paper or sticky note.

- Each team member takes it in turn to ask the project owner whether their question is in or out of scope.

- The project owner answers by placing the question in or out. (No question can be placed on the line. It is either in or out.) It will look something like figure 1.4.

- Write it up as part of your project challenge and scoping.

Figure 1.4: scoping

Back to our airline example, we unpack through this process that the audience (who) is families who can afford to travel long haul, but aren’t (why) and the occasion/journey stage (when and where) is the in-flight experience. At this stage all potential in-flight solutions are in scope (what).

3. Rephrase the challenge

| TIME 15–25 minutes |

| PEOPLE Core team of 6–10 |

| MATERIALS A whiteboard/flip chart paper, markers and sticky notes |

Once we feel we are at the right level of focus and we know what is in and out of scope, we then turn to phrasing the challenge in the right way to inspire and engage people’s natural creativity.

- Start by writing the challenge in the ‘How might we … ’ (HMW) format. Our brains are more likely to solve problems if we phrase them as questions. HMW also encourages us to believe that the challenge can be solved.

- Then make sure it is positive. A negative sentence can take a lot more brain power to deal with. Positive statements are much more motivating.

- Next, write the challenge in a customer-centric way. We want our challenges to be focused on uncovering and solving real customer needs.

- Check that the challenge statement:

- – truly excites you

- – has no solutions baked in

- – has no jargon.

- Write up your final challenge statement.

For example, there is an old story of a Toyota executive who asked employees to come up with ‘ways to increase their productivity’, but recieved only blank stares in response.

However, when they instead asked ‘How might we make your jobs easer?’ they were flooded with suggestions.

Tip

Our brains love questions. The more engrossing the question is, the harder our brains will work to answer it. This problem solving begins immediately and continues, whether we are conscious of it or not (incubating).

Returning to the airline example, our rephrased airline innovation challenge then becomes something like:

How might we improve the in-flight experience on long-haul travel for families with young children and a low propensity to travel, so they can enjoy the benefits of travel?

Write up final project challenge and brief

We use the project brief template to capture all key information about the challenge, forcing important questions to be asked upfront and to align the team. Key sponsors and stakeholders should then sign this off before progressing. The briefing template is continually referenced, to see how the project is tracking versus the original objectives.

Designing a physical space

Innovation is a much more visual and ‘solve by doing’ approach than most business as usual projects. You’re standing, creating, writing with markers on sticky notes and working in groups. Some might call it messy due to the number of sticky notes, butcher paper, whiteboards, prototypes and so on in use and on display. Often, in business as usual projects, we try and think of the solution before we build. Our workspaces tend to be a desk with a computer in an open plan office, and meeting rooms where we talk, not do. Whereas in innovation we borrow from ‘designers’ — solving by doing and making. You need a space that not only enables this, but also encourages these behaviours. You also need at least three times as much space per person as you’d normally allow for in a meeting room. Innovation can be as much about the space and artefacts you use as the methods and tools. As Joshua Handy, head of Innovation at Method cleaning products, said,

… we try to think of design as a culture rather than a strategy. … we have a culture that is all about design so part of that is about collaboration, communication, and transparency. When we walk around the office, everyone’s thinking is on the walls.

So what does this actually look like?

Wall space

You’ll need plenty of wall space and/or whiteboards for completing your innovation activities. I actually find having both is great, and you can use the whiteboards as movable and usable walls between each team zone. I’ll have more on breaking your project team up into sub-teams in stage 4: Ideate, but for now it is worth considering you’ll want space for up to four sub-teams during key workshops. You’ll find that just about every stage of the front end of innovation journey uses templates and canvases that are populated with insights and ideas on sticky notes. It is far easier doing this and visualising it on a wall. It also gets you on your feet, which means you have more energy. There’ll be other times for sitting down. Think of it like a TV detective’s workspace as they’re trying to solve a crime. The space should:

- encourage action and solving by doing

- signal failure is okay

- have a designated space for making simple, quick and low-cost mock-ups (prototypes) of products

- have acoustic, not visual, separation between team zones. So it is more ‘car garage’ than ‘car showroom’.

Permanency

You’ll also need your thinking and artefacts to stay up. You are going to be evolving and iterating these. Having to take them down at the end of every day, store them and then find a new room the next day and repeat it over and over again will just result in lost ideas and wasted time and energy. Time that should be going into understanding your customers and innovating! Having your customers’ insights and ideas up permanently on a wall (until project completion) also makes it easier for stakeholder walk-throughs and showcases. So get permission for a dedicated space.

Plenary space

You’ll also need a central space for the team to get together and instruct tasks to others in workshops and so on. This is where seating is suitable. You can go with just chairs, add tables, or make it more relaxed, with couches and beanbags. Just remember, design it for how you want to use the space.

It is also great to put everything on wheels. When Stanford’s d.school redesigned their space they took inspiration from the stage in performing arts. Everything was made movable — walls, whiteboards, even the couches were on wheels. It makes you want to dive straight in and do stuff. No obstacle is a barrier.

Hopefully you’ve found this section on getting started useful. But if you’re like me you’re probably itching to get into it. Next, in stage 2, it’ll be time to dive in and immerse yourselves into the world of the customer.

Learnings

- Minimise innovation failure and mistakes through poor handovers between teams and silos by running cross-functional teams that work side by side. Involve the designers, developers and other BEI (back end of innovation) resources early in the journey.

- Innovation loves focus. Have a clear challenge you are trying to solve. This is best served through having an innovation strategy, which consists of clear innovation opportunity areas.

- Make sure your challenge statement is customer-centric. Remember that, while you might be starting with a business challenge, unless you are improving the customer’s life in some way it is unlikely to be successful.

- Get your team performing and collaborating as early as possible in the project through preparation, team building exercises, clear roles and responsibilities and managing conflict constructively.

- Find and designate a willing senior leader to be the project’s champion. This needs to be someone who can provide project legitimacy, ground cover, free up the necessary time and resources, make connections and remove barriers.

Questions for innovators and leaders

- Does your organisation and/or division have an innovation strategy that outlines the key opportunities for growth? What are they and how are you working towards fulfilling them?

- How do you currently set your innovation teams up for success? Do you put experienced project leaders and managers on the more difficult and disruptive innovation projects and groom less experienced team members on core and incremental projects? While also keeping a mix of exuberant youth and experience across all projects?

- Do you run your innovation projects with cross-functional teams, or siloed teams with handovers?

- Do you apply effort and focus to team dynamics and performance, or are teams just expected to get on with it? What can you learn from successful high-performing teams such as sports teams?

- Is there space in your organisation for people to conduct the messy, tactile and visual front end of innovation?