What Is a Project?

Things are not always what they seem.

—Phaedrus, Roman writer and fabulist

CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Express a business need in terms of a problem or opportunity

- Understand how goal and solution can be used to define project types

- Appreciate the challenges of the complex project landscape

- Define a project, program, and portfolio

- Define a complex project

- Understand the Scope Triangle

- Envision the Scope Triangle as a system in balance

- Prioritize and apply the Scope Triangle for improved change management

- Know the importance of classifying projects

- Understand the project landscape and how it is applied

To put projects into perspective, you need a definition—a common starting point. All too often, people call any work they have to do a project. Projects actually have a specific definition. If a set of tasks or work to be done does not meet the strict definition, then it cannot be called a project. To use the project management techniques presented in this book, you must first have a project.

UNIQUE VALUE PROPOSITIONS

The classification of a project based on a clear or not clear statement of the project goal and solution is the foundation for the learning and discovery of effective project management. Every project falls in only one quadrant of the four‐quadrant matrix at a time and establishes the issues and opportunities for solution discovery.

The new systems‐oriented definition of the Scope Triangle creates a unique tool for understanding the relationships between the scope variables including risk and offers help with problem‐solving and decision‐making.

This chapter introduces a different definition of a project—one that focuses on the generation of business value as the only success criteria. To that end we are redefining the project as a business‐focused definition.

Defining a Project

Projects arise out of unmet needs. Some projects have been done several times under similar situations and are relatively risk free. Others can be quite complex for a variety of reasons. Those unmet needs might be to find a solution to a critical business problem that has evaded prior attempts at finding a solution. Or those needs might be to take advantage of an untapped business opportunity. In either case, a sponsor or customer prepares a business case to advocate approval to pursue the appropriate project. Beginning with the projects that fall somewhere between these very different types of projects, the main focus of this book is to develop the best‐fit project management approaches. This is and will continue to be a major challenge even for the most skilled and creative project teams. The formal definition of that effort follows.

DEFINITION: PROJECT

A project is a sequence of unique, complex, and connected activities that have one goal or purpose and that must be completed by a specific time, within budget, and according to specification.

This definition works well for simple projects, but we will find reason to modify it for more complex projects. It is a commonly accepted definition of a project and tells you quite a bit. Let's take a closer look at each part of the definition.

Sequence of Activities

A project comprises a number of activities that must be completed in some specified order, or sequence. For now, an activity is a defined chunk of work. Chapter 7, “How to Plan a TPM Project,” formalizes this definition.

The sequence of the activities is based on technical requirements, not on management prerogatives. To determine the sequence, it is helpful to think in terms of inputs and outputs. The output of one activity or set of activities becomes the input to another activity or set of activities.

Specifying a sequence based on resource constraints or statements such as “Pete will work on activity B as soon as he finishes working on activity A” should be avoided because this establishes an artificial relationship between activities. What if Pete wasn't available at all? Resource constraints aren't ignored when you actually schedule activities. The decision of what resources to use and when to use them comes later in the project planning process.

Unique Activities

The activities in a project are unique. Something is always different each time the activities of a project are repeated. Usually the variations are random in nature—for example, a part is delayed, someone is sick, or a power failure occurs. These random variations are the challenge for the project manager and what contributes to the uniqueness of the project.

Complex Activities

The activities that make up the project are not simple, repetitive acts, such as mowing the lawn, painting the rooms in a house, washing the car, or loading the delivery truck. Instead they are complex. For example, designing an intuitive user interface to an application system is a complex activity. Most activities in the contemporary project are complex while some are still simple.

Connected Activities

Being connected implies a logical or technical relationship between pairs of activities. There is an order to the sequence in which the activities that make up the project must be completed. They are considered connected because the output from one activity is the input to another. For example, you must design the computer program before you can program it.

You could have a list of unconnected activities that must all be complete in order to complete the project. For example, consider painting the interior rooms of a house. With some exceptions, the rooms can be painted in any order. The interior of a house is not completely painted until all its rooms have been painted, but they can be painted in any order. Painting the house is a collection of activities, but it is not considered a project according to the definition.

One Goal

Projects must have a single goal —for example, to design an inner‐city playground for AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) families. However, very large or complex projects may be divided into several subprojects, each of which is a project in its own right. This division makes for better management control. For example, subprojects can be defined at the department, division, or geographic level. This artificial decomposition of a complex project into subprojects often simplifies the scheduling of resources and reduces the need for interdepartmental communications while a specific activity is worked on. The downside is that the projects are now interdependent. Even though interdependency adds another layer of complexity and communication, it can be handled.

Specified Time

Projects are finite. They have a beginning and an end. Processes are continuous. They repeat themselves. Projects have a specified completion date. This date can be self‐imposed by management or externally specified by a client or government agency. The deadline is beyond the control of anyone working on the project. The project is over on the specified completion date whether or not the project work has been completed.

Being able to give a firm completion date requires that a start date also be known. Absent a start date the project manager can only make statements like, “I will complete the project 6 months after I start the project.” In other words, the project manager is giving a duration for the project. Senior management wants a deadline.

Within Budget

Projects also have resource limits, such as a limited amount of people, money, or machines that can be dedicated to the project. These resources can be adjusted up or down by management, but they are considered fixed resources by the project manager. For example, suppose a company has only one web designer. That is the fixed resource available to project managers. If the one web designer is fully scheduled, the project manager has a resource conflict that he or she cannot resolve.

REFERENCE

Chapter 6, “How to Scope a TPM Project,” and Chapter 8, “How to Launch a TPM Project,” cover resource limits and scheduling in more detail.

Resource constraints become operative when resources need to be scheduled across several projects. Not all projects can be scheduled because of the constraining limits on finite resources. That brings management challenges into the project approval process.

According to Specification

The client, or the recipient of the project's deliverables, expects a certain level of functionality and quality from the project. These expectations can be self‐imposed, such as the specification of the project completion date, or client‐specified, such as producing the sales report on a weekly basis.

Although the project manager treats the specification as fixed, the reality of the situation is that any number of factors can cause the specification to change. For example, the client may not have defined the requirements completely at the beginning of the project, or the business situation may have changed (which often happens in projects with long durations). It is unrealistic to expect the specification to remain fixed through the life of the project. Systems specification can and will change, thereby presenting special challenges to the project manager.

REFERENCE

Chapter 6, “How to Scope a TPM Project,” and Chapter 7, “How to Plan a TPM Project,” describe how to effectively handle client requirements.

Specification satisfaction has been a continual problem for the project manager and accounts for a large percentage of project failures. Project managers deliver according to what they believe are the correct specifications only to find out that the customer is not satisfied. Somewhere there has been an expectation or communications disconnect. The Conditions of Satisfaction (COS) process (discussed in Chapter 6, “How to Scope a TPM Project”) is one way of managing potential disconnects.

A Business‐Focused Definition of a Project

The major shortcoming of the preceding definition of a project is that it isn't focused on the purpose of a project, which is to deliver business value to the client and to the organization. So, lots of examples exist of projects that meet all of the constraints and conditions specified in the definition, but the client is not satisfied with the results. The many reasons for this dissatisfaction are discussed throughout the book. So, I offer a better definition of a project for your consideration.

DEFINITION: BUSINESS‐FOCUSED PROJECT

A project is a sequence of finite dependent activities whose successful completion results in the delivery of the expected business value that validated doing the project.

The major focus of every project is the satisfaction of client needs through the generation of the expected business value. That will be the primary metric for assessing project performance and progress.

An Intuitive View of the Project Landscape

Projects are not viewed in isolation. The enterprise will have collections of all types of projects running in parallel and drawing on the same finite resources, so you will need a way of describing that landscape and providing a foundation for management decision‐making.

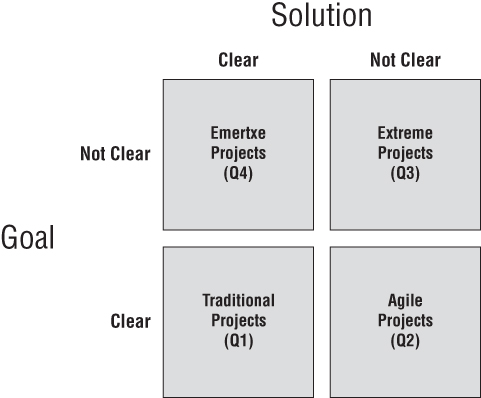

I like simple and intuitive models, so I have defined a project landscape around two characteristics: goal and solution. Every project must have a goal and a solution. You could use a number of metrics to quantify these characteristics, but the simplest and most intuitive will be two values: clear and complete or not clear and incomplete. Two values for each characteristic generate the four‐quadrant matrix shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: The four quadrants of the project landscape

I don't know where the dividing line is between clear and not clear, but that is not important to this landscape. These values are conceptual, not quantifiable, and their interpretation is certainly more subjective than objective. A given project can exhibit various degrees of clarity. The message in this landscape is that the transition from quadrant to quadrant is continuous and fluid. To further label these projects, traditional projects are found in Quadrant 1; Agile projects are found in Quadrant 2; Extreme projects are found in Quadrant 3, and Emertxe (pronounced ee‐MERT‐zee) projects are found in Quadrant 4. Traditional projects are defined and discussed in Part II, “Traditional Project Management.” Complex projects (Agile, Extreme, and Emertxe) are defined and discussed in Part III, “Complex Project Management.”

As an example, say that the project goal is to cure the common cold. Is this goal statement clear and complete? Not really. The word cure is the culprit. Cure could mean any one of the following:

- Prior to birth, the fetus is injected with a DNA‐altering drug that prevents the person from ever getting a cold.

- As part of everyone's diet, they take a daily dose of the juice from a tree that grows only in certain altitudes in the Himalayas. This juice acts as a barrier and prevents the onset of the common cold.

- Once a person has contracted a cold, they take a massive dose of tea made from a rare tree root found only in central China, and the cold will be cured within 12 hours.

So, what does cure really mean? As another example, consider this paraphrasing of a statement made by President John F. Kennedy during his Special Message to Congress on urgent national needs on May 25, 1961: By the end of the decade, we will have put a man on the moon and returned him safely to earth. Is there any doubt in your mind that this goal statement is clear and complete? When the project is finished, will there be any doubt in your mind that this goal has or has not been achieved?

Every project that ever existed or will exist falls into only one of these four quadrants at any point in time. This landscape is not affected by external changes of any kind. It is a robust landscape that will remain in place regardless. The quadrant in which the project lies will provide an initial guide to choosing a best‐fit project management life cycle (PMLC) model and adapting its tools, templates, and processes to the specific characteristics of the project. As the project work commences and the goal and solution become clearer, the project's quadrant can change, and perhaps the PMLC will then change as well; however, the project is always in one quadrant. The decision to change the PMLC for a project already underway may be a big change and needs to be seriously considered. Costs, benefits, advantages, and disadvantages are associated with a mid‐project change of PMLC. Chapter 14, “Hybrid Project Management Framework,” offers some advice for making this decision.

Beyond clarity and completeness of the goal and solution, you have several other factors to consider in choosing the best‐fit PMLC and perhaps modifying it to better accommodate these other factors. By way of example, one of those factors is the extent to which the client has committed to be meaningfully involved. If the best‐fit PMLC model requires client involvement that is heavy and meaningful, as many complex projects do, and you don't expect to have that involvement, you may have to fall back to an approach that doesn't require as much client involvement or includes other preparatory work on your part. For example, you may want to put a program in place to encourage the desired client involvement in preparation for using the best‐fit PMLC model. This is a common situation, and you learn strategies for effectively dealing with it in Part III, “Complex Project Management.”

Defining a Program

A program is a collection of related projects. The projects may have to be completed in a specific order for the program to be considered complete. Because programs comprise multiple projects, they are larger in scope than a single project. For example, the United States Government had a space program that included several projects such as the Challenger Project. A construction company contracts a program to build an industrial technology park with several separate projects.

Unlike projects, programs can have many goals. For example, every launch of a new mission in the NASA space program included several dozen projects in the form of scientific experiments. Except for the fact that they were all aboard the same spacecraft, the experiments were independent of one another and together defined a program.

Defining a Portfolio

A simple definition of a project portfolio is that it is a collection of projects that share some common link to one another. The operative phrase in this definition is “share some common link to one another.” That link could take many forms. At the enterprise level, the link might be nothing more than the fact that all the projects belong to the same company. While that will always be true, it is not too likely the kind of link you are looking for. It is too general to be of any management use. Some more useful and specific common links might be any one of the following:

- The projects may all originate from the same business unit—for example, information technology.

- The projects may all be new product development projects.

- The projects may all be research and development projects.

- The projects may all be infrastructure maintenance projects from the same business unit.

- The projects may all be process improvement projects from the same business unit.

- The projects may all be staffed from the same human resource pool.

- The projects may request financial support from the same budget.

Each portfolio will have an allocation of resources (time, dollars, and staff) to accomplish whatever projects are approved for that portfolio. Larger allocations usually reflect the higher importance of the portfolio and stronger alignment to the strategic plan. One thing is almost certain: whatever resources you have available for the projects aligned to the portfolio, the resources will not be enough to meet all requests. Not all projects proposed for the portfolio will be funded and not all projects that are funded will necessarily be funded 100 percent. Hard choices have to be made, and this is where an equitable decision model is needed.

Your organization will probably have several portfolios. Based on the strategic plan, resources will be allocated to each portfolio based on its priority in the strategic plan, and it is those resources that will be used as a constraint on the projects that can be supported by the specific portfolio.

Understanding the Scope Triangle

You may have heard of the term Iron Triangle or Triple Constraint. It refers to the relationship between Time, Cost, and Scope. These three variables form the sides of a triangle and are an interdependent set. If any one of them changes, at least one other variable must also change to restore balance to the project. That is all well and good, but there is more to explain.

Consider the following constraints that operate on every project:

- Scope

- Quality

- Cost

- Time

- Resources

- Risk

Except for Risk these constraints form an interdependent set—a change in one constraint can require a change in one or more of the other constraints in order to restore the equilibrium of the project. In this context, the set of five parameters form a system that must remain in balance for the project to be in balance. Because they are so important to the success or failure of the project, each parameter is discussed individually in this section.

Scope

Scope is a statement that defines the boundaries of the project. It tells not only what will be done, but also what will not be done. In the information systems industry, scope is often referred to as a functional specification. In the engineering profession, it is generally called a Statement of Work (SOW). Scope may also be referred to as a document of understanding, a scoping statement, a project initiation document, or a project request form. Whatever its name, this document is the foundation for all project work to follow. It is critical that the scope be correct. Scope is the most important of the six factors as it changes over the life of the project and can cause significant changes to the project plan.

REFERENCE

Chapter 6, “How to Scope a TPM Project,” describes exactly how this should happen in its coverage of the COS.

Beginning a project on the right foot is important, and so is staying on the right foot. It is no secret that a project's scope can change. You do not know how or when, but it will change. Detecting that change and deciding how to accommodate it in the project plan are major challenges for the project manager.

Quality

The following two types of quality are part of every project:

- Product quality—The quality of the deliverable from the project. As used here “product” includes tangible artifacts like hardware and software as well as business processes. The traditional tools of quality control, discussed in Chapter 5, “What Are Project Management Process Groups?” are used to ensure product quality.

- Process quality—The quality of the project management process itself. The focus is on how well the project management process works and how it can be improved. Continuous quality improvement and process quality management are the tools used to measure process quality.

A sound quality management program with processes in place that monitor the work in a project is a good investment. Not only does it contribute to client satisfaction, but it helps organizations use their resources more effectively and efficiently by reducing waste and revisions. Quality management is one area that should not be compromised. The payoff is a higher probability of successfully completing the project and satisfying the client.

Cost

The dollar cost of doing the project is another variable that defines the project. It is best thought of as the budget that has been established for the project. This is particularly important for projects that create deliverables that are sold either commercially or to an external customer.

Cost is a major consideration throughout the project management life cycle. The first consideration occurs at an early and informal stage in the life of a project. The client can simply offer a figure about equal to what he or she had in mind for the project. Depending on how much thought the client put into it, the number could be fairly close to or wide of the actual cost for the project. Consultants often encounter situations in which the client is willing to spend only a certain amount for the work. In these situations, you do what you can with what you have. In more formal situations, the project manager prepares a proposal for the projected work. That proposal includes an estimate (perhaps even a quote) of the total cost of the project. Even if a preliminary figure has been supplied by the project manager, the proposal allows the client to base his or her go/no‐go decision on better estimates.

Time

The client specifies a time frame or deadline date within which the project must be completed. To a certain extent, cost and time are inversely related to one another. The time a project takes to be completed can be reduced, but costs increase as a result.

Time is an interesting resource. It can't be inventoried. It is consumed whether you use it or not. The objective for the project manager is to use the future time allotted to the project in the most effective and productive ways possible. Future time (time that has not yet occurred) can be a resource to be traded within a project or across projects. Once a project has begun, the prime resource available to the project manager to keep the project on schedule or get it back on schedule is time. A good project manager realizes this and protects the future time resource jealously.

Resources

Resources are assets such as people, equipment, physical facilities, or inventory that have limited availabilities, can be scheduled, or can be leased from an outside party. Some are fixed; others are variable only in the long term. In any case, they are central to the scheduling of project activities and the orderly completion of the project.

For systems development projects, people are the major resource. Another valuable resource for systems projects is the availability of computer processing time (mostly for testing purposes), which can present significant problems to the project manager with regard to project scheduling.

Risk

Risk is not an integral part of the Scope Triangle, but it is always present and spans all parts of the project both external as well as internal, and therefore it does affect the management of the other five constraints.

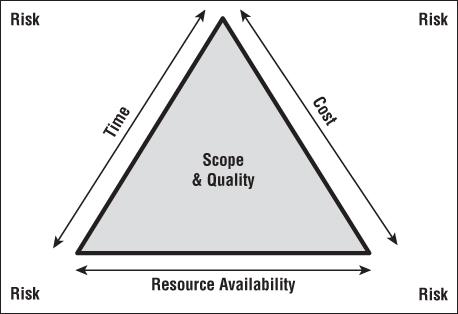

Envisioning the Scope Triangle as a System in Balance

The major benefit of using the Scope Triangle shown in Figure 1.2 instead of the three‐variable Iron Triangle can now be discussed. Projects are dynamic systems that must be kept in equilibrium. Not an easy task, as you shall see! Figure 1.2 illustrates the dynamics of the situation.

Figure 1.2: The Scope Triangle

COMMENT ON THE SCOPE TRIANGLE

While the accountants will tell you that everything can be reduced to dollars, and they are right, you will separate resources as defined here. They are independently controllable by the project manager and need to be separately identified for that reason.

The geographic area inside the triangle represents the scope and quality of the project. Lines representing time, cost, and resource availability bound scope and quality. Time is the window of time within which the project must be completed. Cost is the dollar budget available to complete the project. Resources are any consumables used on the project. People, equipment availability, and facilities are examples.

The project plan will have identified the time, cost, and resource availability needed to deliver the scope and quality of a project. In other words, the project is in equilibrium at the completion of the project planning session and approval of the commitment of resources and dollars to the project. That will not last too long, however. Change is waiting around the corner.

The Scope Triangle offers a number of insights into the changes that can occur in the life of the project. For example, the triangle represents a system in balance before any project work has been done. The sides are long enough to encompass the area generated by the scope and quality statements. Not long after work begins, something is sure to change. Perhaps the client calls with an additional requirement for a feature that was not envisioned during the planning sessions. Perhaps the market opportunities have changed, and it is necessary to reschedule the deliverables to an earlier date, or a key team member leaves the company and is difficult to replace. Any one of these changes throws the system out of balance.

Part III, “Complex Project Management,” discusses projects whose final scope cannot be known until the project is nearly complete. That presents some interesting management challenges to the client and the project manager. Those challenges revolve around the business value delivered by the final solution and the final goal.

The project manager controls resource utilization and work schedules. Management controls cost and resource level. The client controls scope, quality, and delivery dates. Scope, quality, and delivery dates suggest a hierarchy for the project manager as solutions to accommodate the changes are sought.

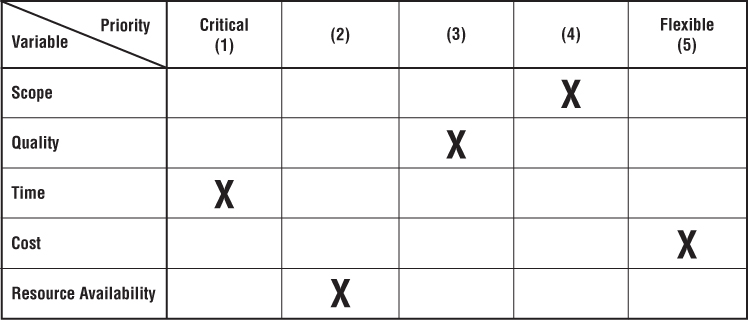

Prioritizing the Scope Triangle Variables for Improved Change Management

The critical component of an effective project management methodology is the scope management process. The five variables that define the Scope Triangle must be prioritized so that the suggested project plan revisions can be prioritized. Figure 1.3 gives an example.

Figure 1.3: Prioritized Scope Triangle variables

A common application of the prioritized Scope Triangle variables occurs whenever a scope change request is made. The analysis of the change request is documented in a Project Impact Statement (PIS). If the change is to be approved, there will be several alternatives as to how that change can be accommodated. Those alternatives are prioritized using the data in Figure 1.3.

Applying the Scope Triangle

There are only a few graphics that I want you to burn into your brain because of their value throughout the entire project life cycle. The Scope Triangle is one such graphic. It will have at least two major applications for you: as a problem escalation strategy and as a reference for the Project Impact Statement, which is created as part of the scope change process.

Problem Resolution

The Scope Triangle enables you to ask the question, “Who owns what?” The answer will give you an escalation pathway from project team to resource manager to client to sponsor. The client and senior management own time, budget, and resources. The project team owns how time, budget, and resources are used. Within the policies and practices of the enterprise, any of these may be moved within the project to resolve problems that have arisen. In solving a problem, the project manager should try to find a solution within the constraints of how the time, budget, and resources are used. Project managers do not need to go outside of their sphere of control.

The next step in the escalation strategy would be for the project manager to appeal to the resource managers for problem resolution. The resource manager owns who gets assigned to a project as well as any changes to that assignment that may arise.

The final step in the problem escalation strategy is to appeal to the client and perhaps to the sponsor for additional resources. They control the amount of time and money that has been allocated to the project. Finally, they control the scope of the project. Whenever the project manager appeals to the client, it will be to get an increase in time or budget and some relief from the scope by way of scope reduction or scope release.

Scope Change Impact Analysis

The second major application of the Scope Triangle is as an aid in the preparation of the Project Impact Statement. This is a statement of the alternative ways of accommodating a particular scope change request of the client. The alternatives are identified by reviewing the Scope Triangle and proceeding in much the same way as discussed in the previous paragraph. Chapter 9, “How to Execute a TPM Project,” includes a detailed discussion of the scope change process and the use of the Project Impact Statement.

The Importance of Classifying Projects

There are many ways to classify a project, such as the following:

- By size (cost, duration, team, business value, number of departments affected, and so on)

- By type (new, maintenance, upgrade, strategic, tactical, operational)

- By application (software development, new product development, equipment installation, and so on)

- By complexity and uncertainty (see Chapter 11, “Complexity and Uncertainty in the Project Landscape”)

Projects are unique and to some extent so is the best‐fit model to manage them. Part III, “Complex Project Management,” is devoted to exploring the best fit models and when to use them. For now, it is sufficient to understand that a one‐size‐fits‐all approach to project management doesn't work and has never worked. It is far more effective to group projects based on their similarities and to use a project management approach designed specifically for each project type. That is the topic of this section.

Establishing a Rule for Classifying Projects

For the purposes of this chapter, two different rules are defined here. The first is based on the characteristics of the project, and the second is based on the type of project.

Classification by Project Characteristics

Many organizations choose to define a classification of projects based on such project characteristics as the following:

- Risk —Establish levels of risk (high, medium, and low).

- Business value —Establish levels (high, medium, and low).

- Length —Establish several categories (such as 3 months, 3 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, and so on).

- Complexity —Establish categories (high, medium, and low).

- Technology used —Establish several categories (well‐established, used occasionally, used rarely, never used).

- Number of departments affe cted—Establish some categories (such as one, a few, several, and all).

- Cost

The project profile determines the classification of the project. The classification defines the extent to which a particular project management methodology is to be used. In Part III, “Complex Project Management,” you use these and other factors to adjust the best‐fit project management approach.

I strongly advocate this approach because it adapts the methodology to the project. “One size fits all” does not work in project management. In the final analysis, I defer to the judgment of the project manager. In addition to the parts required by the organization, the project manager should adopt whatever parts of the methodology he or she feels improves his or her ability to help successfully manage the project. Period.

Project characteristics can be used to build a classification rule as follows:

- Type A projects —These are high‐business‐value, high‐complexity projects. They are the most challenging projects the organization undertakes. Type A projects use the latest technology, which, when coupled with high complexity, causes risk to be high also. To maximize the probability of success, the organization requires that these projects utilize all the methods and tools available in their project management methodology. An example of a Type A project is the introduction of a new technology into an existing product that has been very profitable for the company.

- Type B projects —These projects are shorter in length, but they are still significant projects for the organization. All of the methods and tools in the project management process are probably required. Type B projects generally have good business value and are technologically challenging. Many product development projects fall in this category.

- Type C projects —These are the projects that occur most frequently in an organization. They are short by comparison and use established technology. Many are projects that deal with the infrastructure of the organization. A typical project team consists of five people, the project lasts 6 months, and the project is based on a less‐than‐adequate scope statement. Many of the methods and tools are not required for these projects. The project manager uses those optional tools only if he or she sees value in their use.

- Type D projects —These just meet the definition of a project and may require only a scope statement and a few scheduling pieces of information. A typical Type D project involves making a minor change in an existing process or procedure or revising a course in the training curriculum.

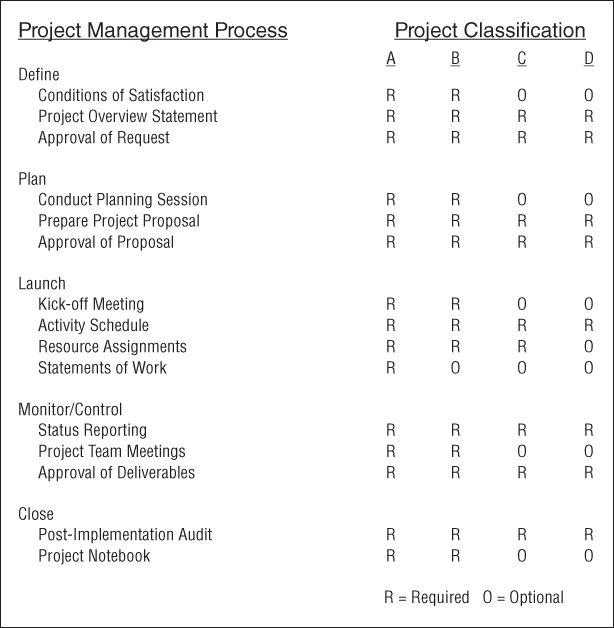

Table 1.1 gives a hypothetical example of a classification rule.

Table 1.1: Example of Project Classes and Definitions

| CLASS | DURATION | RISK | COMPLEXITY | TECHNOLOGY | LIKELIHOOD OF PROBLEMS |

| Type A | > 18 months | High | High | Breakthrough | Certain |

| Type B | 9–18 months | Medium | Medium | Current | Likely |

| Type C | 3–9 months | Low | Low | Best of breed | Some |

| Type D | < 3 months | Very low | Very low | Practical | Few |

These four types of projects might use the parts of the methodology shown in Figure 1.4. The figure lists the methods and tools that are either required or optional, given the type of project.

Figure 1.4: The use of required and optional parts of the methodology by type of project

Classification by Project Application

Many situations exist in which an organization repeats projects that are of the same type. Following are some examples of project types:

- Installing software

- Recruiting and hiring

- Setting up hardware in a field office

- Soliciting, evaluating, and selecting vendors

- Updating a corporate procedure

- Developing application systems

These projects may be repeated several times each year and probably will follow a similar set of steps each time they are done.

REFERENCE

You look at the ramifications of that repetition in Chapter 7, “How to Plan a TPM Project,” when Work Breakdown Structure templates are discussed.

The Contemporary Project Environment

The contemporary project environment is characterized by high speed, high change, lower costs, complexity, uncertainty, and a host of other factors. This presents a daunting challenge to the project manager as is described in the sections that follow.

High Speed

The faster products and services get to market, the greater will be the resulting value to the business. Current competitors are watching and responding to unmet opportunities, and new competition is waiting and watching to seize upon any opportunity that might give them a foothold or expansion in the market. Any weakness or delay in responding may just give them that advantage. This need to be fast translates into a need for the project management approach to not waste time—to rid itself, as much as possible, of spending time on non‐value‐added work. Many of the approaches you will study are built on that premise.

The window of opportunity is narrowing and constantly moving. Organizations that can quickly respond to those opportunities are organizations that have found a way to reduce cycle times and eliminate non‐value‐added work as much as possible. Taking too long to roll out a new or revamped product can result in a missed business opportunity. Project managers must know how and when to introduce multiple release strategies and compress project schedules to help meet these requirements. Even more importantly, the project management approach must support these aggressive schedules. That means that these processes must protect the schedule by eliminating all non‐value‐added work. You simply cannot afford to burden your project management processes with a lot of overhead activities that do not add value to the final deliverables or that may compromise your effectiveness in the markets you serve.

Effective project management is not the product of a rigid or fixed set of steps and processes to be followed on every project. Rather, the choice of project management approach is based on having done due diligence on the project specifics and defined an approach that makes sense. I spend considerable time on these strategies in later chapters.

High Change

Clients are often making up their minds or changing their minds about what they want. The environment is more the cause of high change than is any ignorance on the part of the client. The business world is dynamic. It doesn't stand still just because you are managing a project. The best‐fit project management approach must recognize the realities of frequent change, accommodate it, and embrace it. The extent to which change is expected will affect the choice of a best‐fit PMLC model.

Change is constant! I hope that does not come as a surprise to you. Change is always with you and seems to be happening at an increasing rate. Every day you face new challenges and the need to improve yesterday's practices. As John Naisbitt says in The Third Wave, “Change or die.” For experienced project managers as well as “wannabe” project managers, the road to breakthrough performance is paved with uncertainty and with the need to be courageous, creative, and flexible. If you simply rely on a routine application of someone else's methodology, you are sure to fall short of the mark. As you will see in the pages that follow, I have not been afraid to step outside the box and outside my comfort zone. Nowhere is there more of a need for change and adaptation than in the approaches we take to managing projects.

Lower Cost

With the reduction in management layers (a common practice in many organizations) the professional staff needs to find ways to work smarter, not harder. Project management includes a number of tools and techniques that help the professional manage increased workloads. Your staffs need to have more room to do their work in the most productive ways possible. Burdening them with overhead activities for which they see little value is a sure way to failure.

In a landmark paper, “The Coming of the New Organization,” written more than 20 years ago but still relevant, Peter Drucker [Drucker, 1988] depicts middle managers as either ones who receive information from above, reinterpret it, and pass it down, or ones who receive information from below, reinterpret it, and pass it up the line. Not only is quality suspect because of personal biases and political overtones, but also the computer is perfectly capable of delivering that information to the desk of any manager who has a need to know. Given these factors, plus the politics and power struggles at play, Drucker asks why employ middle managers? As technology advances and acceptance of these ideas grows, we have seen the thinning of the layers of middle management. Do not expect them to come back; they are gone forever. The effect on project managers is predictable and significant. Hierarchical structures are being replaced by organizations that have a greater dependence on projects and project teams, resulting in more demands on project managers.

Increasing Levels of Complexity

All of the simple problems have been solved. Those that remain are getting more complex with each passing day. At the same time that problems are getting more complex, they are getting more critical to the enterprise. They must be solved. We don't have a choice. Not having a simple recipe for managing such projects is no excuse. They must be managed, and we must have an effective way of managing them. This book shows you how to create common‐sense project management approaches by adapting a common set of tools, templates, and processes to even the most complex of projects.

More Uncertainty

With increasing levels of complexity come increasing levels of uncertainty. The two are inseparable. Adapting project management approaches to handle uncertainty means that the approaches must not only accommodate change, but also embrace it and become more effective as a result of it. Change is what will lead the team and the client to a state of certainty with respect to a viable solution to its complex problems. In other words, we must have project management approaches that expect change and benefit from it.

Discussion Questions

- Compare and contrast the two definitions of a project presented in this chapter.

- Suppose the Scope Triangle were modified as follows: Resource Availability occupies the center, and the three sides are Scope, Cost, and Schedule. Interpret this triangle as if it were a system in balance. What is likely to happen when a specific resource on your project is concurrently allocated to more and more projects? As project manager, how would you deal with these situations? Be specific.

- Where would you be able to bring about cost savings as a program manager for a company? Discuss these using the standard project constraints.